No great composer achieved their greatness in a vacuum. Although the narratives of music history often ignore them, all of the great composers had female relatives, friends, and colleagues who were major influences on their artistry.

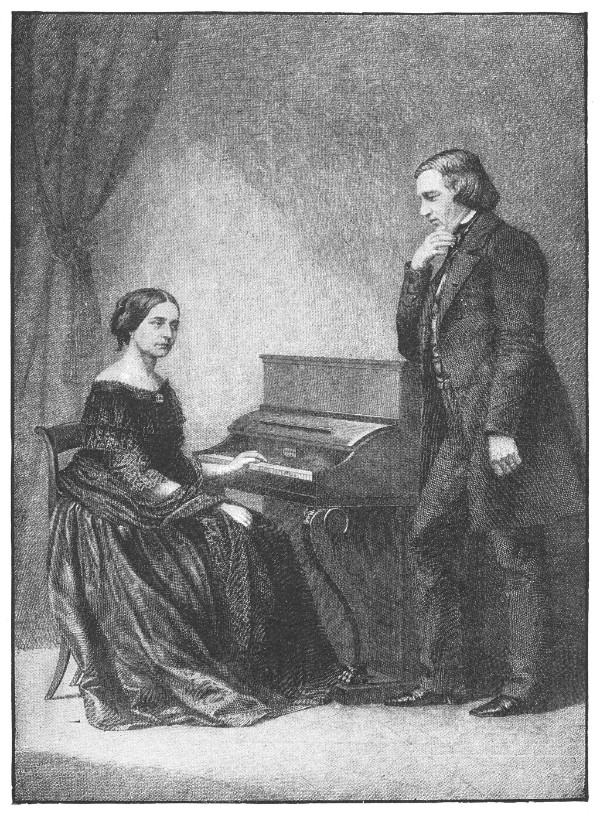

Robert Schumann, 1839

Today, we’re looking at seven women who played important roles in Robert Schumann’s life, from his famous pianist wife to his jilted pianist fiancée to a famous poet who tried to help him escape from the asylum where he died.

Clara Wieck Schumann, wife (1819-1896)

Andreas Staub: Clara Wieck, 1839

Of course, the most important woman in Robert Schumann’s life was his wife and creative partner, Clara Wieck Schumann.

Clara Wieck was born in Leipzig in 1819, the daughter of an ambitious piano teacher named Friedrich and a singer mother.

Friedrich was abusive, and because of that and other reasons, Clara’s mother divorced him. Clara stayed with her mother until the time she was five, then, according to law, was delivered back to her father. This change was very traumatic for her, and there was a long time when she didn’t even speak.

Friedrich Wieck had grand plans for his daughter: he wanted to mold her into a virtuoso to serve as a walking advertisement for his studio and music shop. He pushed her hard, and because of his aggressive tuition, or maybe despite it, she ended up becoming one of the great piano prodigies of her generation.

Robert Schumann met Clara when he was eighteen and she was nine. He was so impressed by her playing that he asked to move into his father’s house to learn from him. Clara grew up with Robert nearby.

When she was in her late teens, they began developing feelings for each other. They had a stormy courtship because Friedrich did not have faith in Robert to be a consistent provider (plus, he wasn’t keen on the idea of his walking advertisement leaving home). However, despite his objections, they were married in 1840, the day before Clara’s twenty-first birthday.

The two were personal and professional partners for the rest of Robert’s life. They had eight children together, and Clara devoted a large part of her career to championing Robert’s music. After Robert died in 1856, Clara never remarried.

Johanna Christiane Schnabel Schumann, mother (1767-1836)

Christiane Schnabel Schumann

Christiane Schnabel was born in 1767 in Karsdorf, Germany, outside of Leipzig. Later, her family moved to the town of Zeitz, also near Leipzig, where her father began working as the town surgeon.

In 1793, a bookshop assistant named August Schumann began rooming with the Schnabels. August was twenty years old and Christiane was twenty-six. They fell in love and two years later, they were married.

The Schumanns eventually moved to the town of Zwickau, Germany, and had five children. Robert was the baby of the family, arriving in 1810 when his mother was forty-three.

Christiane was a musical woman and she encouraged her son’s musical interests. However, after the death of her husband, Christiane decided it would be prudent for Robert to become a lawyer.

In 1830, she wrote a famous letter to Friedrich Wieck, asking him to give her an honest assessment of her son’s musical abilities. Wieck told her that, with time, he would be able to mold him into a concert pianist. (That prediction ended up being a bit over-optimistic.)

In 1832 Robert came to Zwickau and gave a concert for his family. Thirteen-year-old Clara Wieck was also there. Christiane was impressed and told her that she should marry Robert someday.

In December 1835, Robert and Clara went on another visit to Zwickau, and it was there that they confessed their love to one another. However, Christiane died in 1836 before she could witness their wedding.

Marie Schumann, daughter (1841-1929)

Marie Schumann

Marie Schumann was born on 1 September 1841, a few days before her parents’ first wedding anniversary. Felix Mendelssohn was her godfather.

In March 1846, Robert Schumann wrote in his diary that he had begun to teach Marie piano. During her childhood, she had a variety of music teachers, including her father, mother, maternal uncle, and even Johannes Brahms.

Marie was twelve years old when her father’s mental illness became so severe that, after a failed suicide attempt, he moved to an asylum. She never saw him again.

After his breakdown and death, Clara was suddenly under tremendous pressure to provide for her seven surviving children. Clara leaned on Marie to provide support and household organization so that she could continue touring to provide for the family.

Ernestine von Fricken, fiancée (1816-1844)

Ernestine von Fricken

Ernestine von Fricken was born in 1816 in Bohemia, the illegitimate daughter of a wire manufacturer and an unmarried countess.

The countess’s sister was childless, so she and her husband, a man named Ferdinand Ignaz Freiherr von Fricken, adopted Ernestine. He was a composer, flute player, and songwriter.

Ernestine was also musically talented. The family initially wanted her to study with Hummel, but they couldn’t afford to have her stay in Weimar. As a compromise, they went to teacher Friedrich Wieck in Leipzig.

Ernestine von Fricken moved into the Wieck household in 1834, the year she turned eighteen. She was at the house for a few months, from Easter 1834 until September.

Robert Schumann fell in love with her and proposed to her, and she said yes. However, he soon found out that despite its nobility, her family was poor, she was illegitimate, and there would be no inheritance for her future husband. At the same time, he started developing feelings for Clara Wieck. It wasn’t long before the relationship came to an end…to Ernestine’s dismay.

Ernestine’s influence lives on in Schumann’s piano suite Carnaval, which features the name of the town of Asch, where Ernestine was from, written in musical notation and coded into the score.

Schumann: Carnaval, op. 9

Ernestine von Fricken died at the age of twenty-eight of typhus.

Constanze Jacobi, student (1824-1896)

Constanze Jacobi

Constanze Jacobi was born in 1824 in Altenburg, Germany, and came to Leipzig to study music when the Leipzig Conservatory was established in 1843. While there, she studied voice with a mezzo-soprano named Henriette Grabau-Bünau, composition with Felix Mendelssohn, and piano with Robert Schumann.

In 1845 she moved to Dresden. The Schumanns also lived there in the mid-1840s, and she was a frequent guest at their home.

Both Robert and Clara Schumann liked Constanze, and Robert considered her to be one of his best students. In 1849 he dedicated the three songs of his Op. 95 to her, and she premiered his Spanisches Liederspiel, op. 74.

Schumann: Spanisches Liederspiel Op. 74

In 1861, she married a Polish-born German actor named Bogumil Dawison, a celebrated actor who specialized in Hamlet. She was widowed in 1872 and we know nothing more about her life afterward. She died in Dresden in 1896.

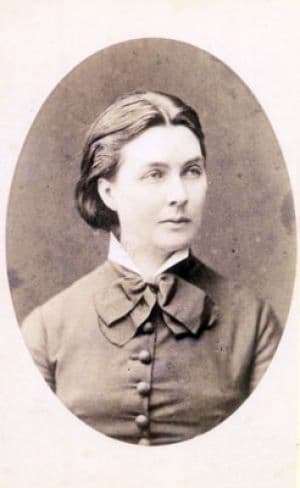

Robena Ann Laidlaw, colleague (1819-1901)

Robena Ann Laidlaw

Robena Ann Laidlaw was born in 1819 in Yorkshire, England, the daughter of a Scottish merchant and Irish mother. She studied in Edinburgh before embarking on career-building travels with her father. She worked, lived, toured, or studied in countless cities: Berlin, London, Hanover, Dresden, Vienna, and St. Petersburg, among others.

She went to visit Robert Schumann when she was in Leipzig in 1837. He was extremely informal, greeting her in his dressing gown, and seemed embarrassed. However, they got along well and found they had a lot of shared interests to talk about.

However, Clara Wieck was not a fan, writing in her diary, “What a miserable and tasteless concert that was! A Beethoven Concerto (completely misconceived), Berger Études (obviously good enough for dilettantes to present them to an audience), a Chopin Étude and a Hiller Étude. And at the end the Military Fantasia by Pixis with whom she had taken lessons for some time, but that last piece did not do him much honour because she played it (like everything else) in one go like a machine, and, on top of that, on a very bad instrument – that was the concert!”

Robert was more impressed. He came to a performance of hers at the Leipzig Gewandhaus concert hall and was at least somewhat impressed, praising in his music magazine Neue Zeitschrift für Musik her “thoroughly good and specific playing,” although he too took issue with her repertoire choice.

Despite any lukewarm praise in his magazine, he was still inspired by her. He came out of a months-long creative funk to write the eight pieces that make up his Fantasiestücke.

Schumann: Fantasiestücke, Op. 12 (Seong-Jin Cho, piano)

Bettina Brentano von Arnim, friend (1785-1859)

Bettina Brentano

Writer and composer Bettina von Arnim was one of the great figures of the early Romantic era. She was born in Frankfurt in 1785, and from an early age, she bemoaned conventionalities.

In 1807, she fell in love with Goethe. (He didn’t return the passion, but he did answer her letters.) In 1810, she met and befriended Beethoven. In 1811, she married a famous German poet named Achim von Arnim.

In 1835 Robert Schumann wanted Bettina to publish some of her music in a Neue Zeitschrift für Musik supplement. The supplement never materialized, but it did kick off their friendship.

In 1837 Clara met her in Berlin and described her in her journal: “Very witty, fiery woman – nothing but wrong judgments as far as music is concerned. She overflows with humor.”

The Schumanns and von Arnim visited each other in Dusseldorf in October 1853, the same month that the Schumanns met Brahms. Robert was just months away from his failed suicide attempt.

He dedicated his five-movement piano solo Gesänge der Frühe (“Songs of the Morning”) to von Arnim, who he called “the high poetess.”

Robert Schumann: Gesänge der Frühe op.133

Interestingly, von Arnim was one of Schumann’s last visitors at the asylum where he died. She was disturbed by what she saw, writing to Clara Schumann urging her to reconsider having him stay there. However, he died there in 1856.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter