It was in the summer of 1912 when hot off the heels of the sumptuous ballet score Daphnis et Chloé – his biggest creative undertaking to date – Ravel took some time off composing to recover and wait for inspiration to strike. This inspiration came fortuitously during a collaboration with Stravinsky, as the two composers worked on orchestrating some unfinished Mussorgsky together for Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes in Paris.

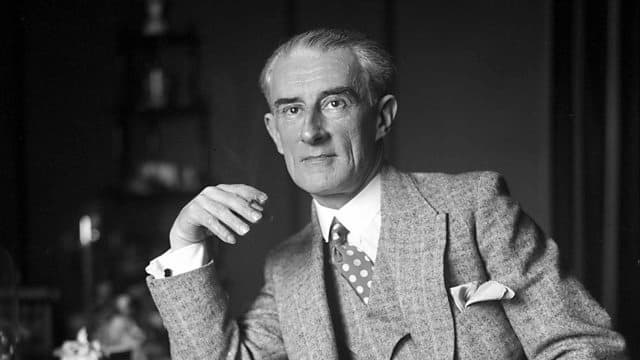

Maurice Ravel © BBC Radio 3

On a completely different scale to Daphnis et Chloé, Ravel’s Trois Poèmes de Mallarmé emerged over the course of two years, Ravel departing from big orchestral scores in favour of a more intimate setup. His choice of orchestration was inspired by Stravinsky’s newly-composed Japanese Lyrics, which he had come across during their recent work together. The Mallarmé poems are scored for soprano with an ensemble of string quartet, flute, clarinet, and piano: exactly the same as the Stravinsky.

Stephane Mallarmé was a symbolist poet. His poetry is full of ambiguous imagery, illusions and allusions, often with no clear subject. The symbolists’ aim was to represent things metaphorically in their poetry without explicitly stating what was going on, and this can be heard throughout Ravel’s settings of these poems: the vocal lines are meandering and speech-like , and the accompaniment flits and changes moods capriciously in response to the fleeting text.

Maurice Ravel: Trois Poèmes de Stéphane Mallarmé par Les Parnassiens

The first movement of Ravel’s Poèmes de Mallarmé is actually dedicated to Stravinsky: ‘Soupir’ (sigh), opening with glittering string harmonics and a vocal line that unfolds slowly and organically, growing with piano notes appearing out of the shimmering, up to a beautiful intimate climax. The movement ends with reminiscences of leaves on the wind and a long ray of sunlight, where we hear the opening material briefly return to bring the movement to a glistening close.

Portrait of Mallarmé, by Nadar, 1896 © Wikipedia

In the second movement, ‘Placet futile’ (Futile petition), we hear of a love for a princess – or rather, the image of one. As the singer gazes longingly at the picture of a princess on painted porcelain cup, we hear of a desire that can never be fulfilled, set against a backdrop of warm strings and snatches of melodies in the flutes and clarinets.

The piano, conspicuously absent for the opening section, changes the direction of the music as the singer becomes agitated with their predicament, the accompaniment voluptuous and volatile. The movement ends with a simple, lullaby-like rocking in the piano, and the final chord unfolds simply and delicately, like the opening of a flower.

The third movement, ‘Surgi de la croupe et du bond’ (Emerging from the croup and the leap), was written over a year after the first two. At the time, Ravel was discovering the music of Arnold Schoenberg and the recently-formed Second Viennese School, and this latecomer to the Mallarmé set is perhaps Ravel’s flirtation with this strand of modernism.

While harmonically adventurous, the first two movements of the Poèmes de Mallarmé are overall still fairly conventional in their use of harmony. Surgi, however, has a different feel altogether. Right from the beginning it feels like the harmonic centre – the chords and materials that keep us anchored to a home key – has almost evaporated.

Igor Stravinsky and Maurice Ravel © Reddit

This unnerving atmosphere pervades throughout the movement, and rightly so. This poem of Mallarmé talks of loneliness, uncertainty and lost love, and is devoid of the sentimentality which is present in the first two. Here, the instrumental writing is stripped back, with cold string harmonics set against chiming bells in the piano – and it is the relative simplicity and stillness of the accompaniment which, when set against the business and intricacy of what came before, creates even more of a chill.

Ravel’s Trois poèmes de Mallarmé are not hugely well-known in his output – at around 12 minutes in duration and for a slightly unusual instrumental setup it can be hard to programme them in a traditional concert. However, despite their brevity, they certainly pack a punch.

The reputation Ravel had for creating perfectly-crafted music – pieces in which no tiny part was out of place – is certainly justified here. It’s hard to believe the range of colours, atmospheres and emotions visited in such a short space of time – and these three fragile and beautiful songs are little gems tucked away in the repertoire.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter