Maurice Ravel was born in Ciboure, France, near the Spanish border on the Bay of Biscay in 1875. He grew up to become one of the most influential composers in French history.

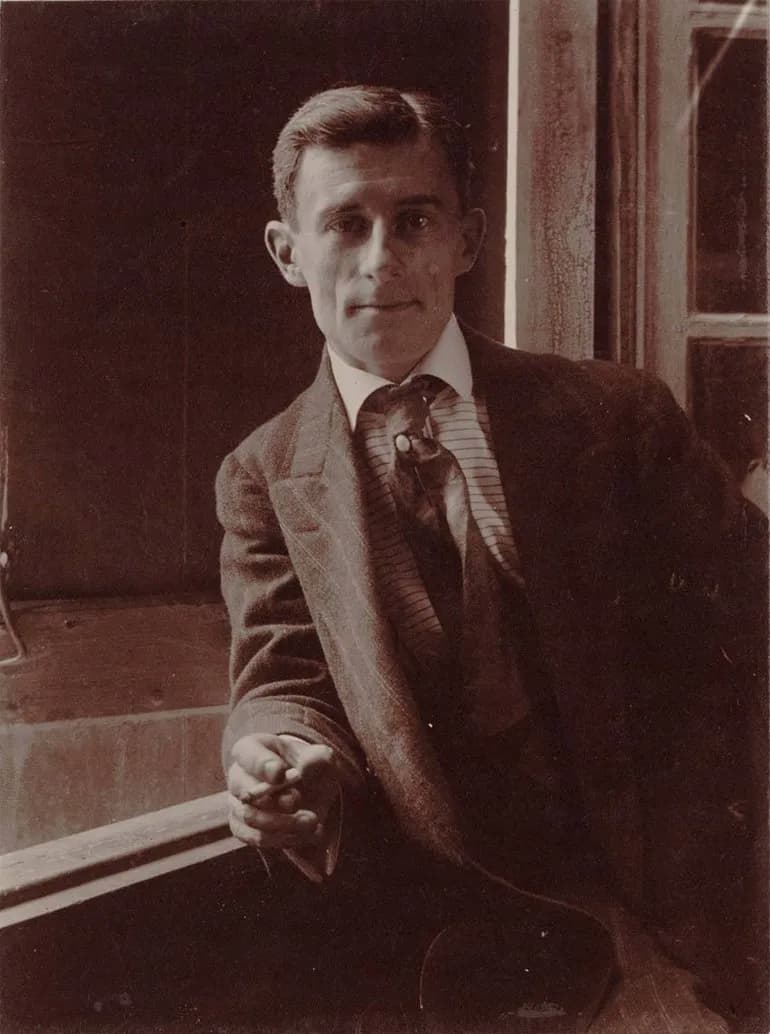

The young Maurice Ravel © debralynnmusic.org

Here are a few facts about his life and work:

- Ravel is associated with the Impressionist movement in music. This style emphasizes mood and atmosphere, sometimes at the expense of strictly following traditional conventions.

- Ravel was a master orchestrator. That means he was an expert at combining different instruments to create new and striking sounds.

- Because of where he was born, Ravel had a fascination with Spanish music and culture. He incorporated Spanish themes and rhythms into several of his compositions.

- His French identity was also very important to him, especially in the aftermath of the Franco-Prussian War of 1871 and, later, World War I.

- Ravel was known for the precision of his music. He has often been compared to a watchmaker. He also was obsessed with things like mechanized children’s toys. This obsession with detail and craftsmanship shows in his music.

Intrigued? Hope so! Here are ten pieces of music:

Pavane pour une infante défunte for piano (1899)

Ravel wrote this piece while still a student at the Paris Conservatoire. The title translates to “Pavane for a Dead Princess.”

Ravel described it as “an evocation of a pavane that a little princess [Infanta] might, in former times, have danced at the Spanish court.”

From the first notes, Ravel creates a melancholic, nostalgic, strangely timeless atmosphere. His use of delicate melodies and poignant harmonies creates a dreamlike quality that transports listeners to a bygone era.

Jeux d’eau (1901)

Translated literally, Jeux d’eau means “Games of Water”, but it has also been translated as “Fountains.”

This is a short, magical piece that perfectly captures the magic of sparkling, tinkling water and flickering sunlight.

It may sound innocuous nowadays, but when it was written, some stalwarts of French music were horrified by the piece’s loose, improvisatory nature. They felt it threatened tradition. Composer Camille Saint-Saëns went so far as to call it “complete cacophony.” Listeners today would disagree.

String Quartet in F major (1902-03)

Although Ravel may have faced resistance from the establishment, the broader public understood his promise. That promise came to a head with his string quartet.

The quartet features a blend of classical structure and impressionistic colors. Ravel weaves intricate melodies and ever-changing textures throughout the work’s four movements.

The second movement, marked “Assez vif et bien rythmé” (Fairly lively and rhythmically), is particularly notable for its playful pizzicato passages and changing tempos. (It starts at 8:45 in the video above.)

The quartet showcases Ravel’s fascination with bringing a fresh approach to traditional forms.

Rapsodie espagnole (1907)

The Rapsodie espagnole (“Spanish Rhapsody”) was one of Ravel’s first big pieces for orchestra.

The colors that he coaxes from the orchestra here are astonishing.

The work has a Spanish atmosphere. The two middle movements are adaptations of Spanish dances—the Malagueña and the Habanera.

Gaspard de la nuit (1908)

“Gaspard de la nuit” translated means “Gaspard of the Night.” Ravel was inspired by the word “gaspard” being the word from Persian for “treasurer” – i.e., someone in a far-away land guarding and keeping track of jewels in the nighttime.

The work is written for piano and contains three movements.

Maurice Ravel, 1925

The first, Ondine, portrays a water nymph seducing someone to visit her underwater kingdom. Notes appear in organic flurries, calling to mind his earlier work Jeux d’eau.

The second, Le Gibet, depicts a hanged man, his corpse swinging on a gibbet in the desert; its atmospheric repetitiveness is haunting.

The finale, Scarbo, is a portrait of a nighttime goblin, as seen by a human lying in bed. Ravel wanted this to be one of the most difficult pieces for piano ever written, and he succeeded. “I wanted to make a caricature of romanticism. Perhaps it got the better of me,” he mused. Even if it did, audiences have adored it – and the entire suite – for over a century.

Daphnis et Chloé Suite No. 2 (1913)

This work was originally meant to be a ballet. Its story charted the romance between the goatherd Daphnis and the shepherdess Chloé.

However, its orchestration by itself is so lush and so stunning, and the music so difficult to dance to, that it’s most often heard today as a concert piece instead of a ballet.

The opening of the second suite is one of the most famous musical portrayals of a sunrise ever, complete with chirping birds in the woodwinds.

An example of Ravel’s cleverness with orchestration is that he instructs the violinists to begin the work all muted, then to take off their mutes one-by-one, creating a gradually increased volume as the sunrise grows brighter.

Trio in A minor (1914)

When Ravel wrote his piano trio, Europe was on the brink of world war. It is easy to wonder if some of that society-wide uneasiness found its way into this sober, achingly beautiful work.

A highlight is the stately, mournful third movement “Passacaille”, a very old form in which a pattern of low notes is repeated over and over with other melodies on top. Combining this old genre with a more modern language contributes to the trio’s strangely timeless nature. The “Passacaille” movement starts at 14:50 in the recording above.

Le Tombeau de Couperin (1914-17)

During and after the cataclysm of WWI, composers reacted to the violence in different ways. Many wrote deeply emotional or dissonant works.

Maurice Ravel as a soldier, 1916

Ravel went in the opposite direction, creating a light and airy piano suite based on eighteenth-century French forms. One can hear the work’s antique, Baroque air.

However, that said, there’s a modern, deeply upsetting twist to this music: every movement is a tribute to one of Ravel’s friends who died in World War I.

Some people thought its light tone was an affront to the tragedies of their deaths. Ravel’s blunt response to the critics was, “The dead are sad enough, in their eternal silence.”

La Valse (1920)

Ravel claimed that his devastating orchestral showpiece La Valse was not about World War I and the destruction of Europe.

“It doesn’t have anything to do with the present situation in Vienna, and it also doesn’t have any symbolic meaning in that regard,” he insisted. “In the course of La Valse, I did not envision a dance of death or a struggle between life and death.”

But if that’s not what it is, what is it?

Ravel’s waltz, the national dance form of the doomed Hapsburg Empire, is an ominous breakdown, full of terrifying, groaning bassoons, threatening growling basses, and devastating cymbal crashes. By the end, it feels as if he has torn apart the entire genre.

This waltz is deeply, deeply warped and unwell. Any ultimate extra-musical meaning, however, has to be decided by the listener.

Boléro (1928)

When Ravel was asked by dancer Ida Rubinstein to create a ballet, he came up with Boléro.

The conceit of the piece is that it is a simple melody repeated over and over again. It has no development in a traditional sense. Rather, Ravel fleshes it out by gradually adding in more and more combinations of instruments until musicians and audiences arrive together at the massive conclusion.

Although the final product proved to be popular, this simple idea has garnered the disgust of some musicians and audiences, who view it as too repetitive to be effective. In the end, once it became very popular, even Ravel himself got tired of it.

Don Quichotte à Dulcinée, song cycle (1932-33)

In 1932, Ravel dipped back into Spanish inspiration one last time, writing three songs inspired by Miguel de Cervantes’s great novel Don Quixote, which traces the adventures of the delusional knight Don Quixote and his unseen idol, the lady Dulcinea del Toboso.

These three sparse, fleeting pieces are unique. Unfortunately, Ravel was so sick by the time he wrote them that he could barely finish them.

Conclusion

Ravel’s health deteriorated in his later years in tragic ways. He started having trouble talking and even holding utensils and had to have his address written on a card and pinned into his coat when he left the house. It’s possible that he had Pick’s Disease.

He died after exploratory brain surgery that was attempting to find out what was wrong. He was 62 years old.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

For us who, amid hundreds of composers, have Ravel on their top 5, well listened to and explored for years, your article was excellent. I wished I had one at my disposal BEFORE I discovered him.

As to “La Valse,” a reminder: the original title was ” Wien,” which is how the Austrians say: Vienna. Also, the original scoring was for two pianos. It’s a marvelous piece to perform, if a duo has the chops.