“People Who Make Music Together Cannot Be Enemies”

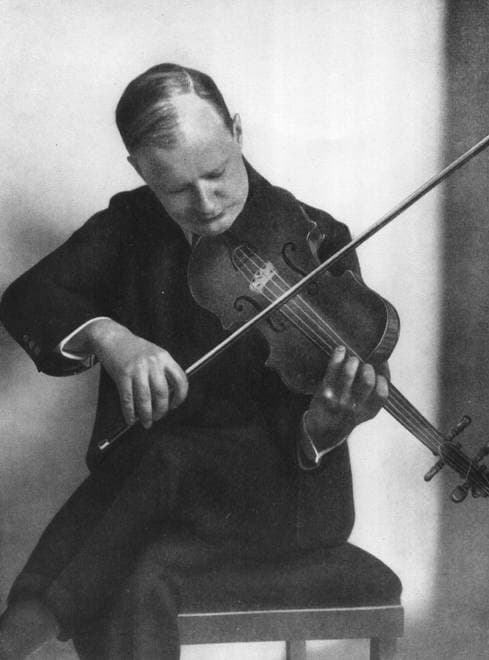

Hindemith playing the viola

Paul Hindemith (1895-1963) unexpectedly died on 28 December 1963 in Frankfurt. And while the general public mourned the loss of a highly respected musician, he had lost all influence on the next generation of composers. As a theorist, he created a new conception of tonality, but as one of his Yale students told me, Hindemith was just too focused on producing additional little Hindemiths. While his works and teaching were popular in the United States in the 1940s, his music was considered taboo by the avant-garde, and he was not accorded fresh relevance throughout the second half of the 20th century.

Paul Hindemith: Symphonic Metamorphosis

A Young Genius

Paul Hindemith in 1901

Born in Hanau, Germany, Paul Hindemith certainly was a precocious musical talent. Whatever he touched, he almost instantaneously mastered. He started violin lessons at an early age and was admitted to the Frankfurt Conservatory at age 12. He soon became an accomplished performer on several instruments, most notably the clarinet and the piano, and also the violin and viola.

At age 19, he was appointed first violinist of the Frankfurt Opera Orchestra. Yet even before he entered the Conservatory, Hindemith had already written his first compositions. Some of these pieces were performed during his Conservatory days and are heavily influenced by Johannes Brahms, a composer he certainly had to come to terms with.

Paul Hindemith: String Quartet No. 1 in C Major, Op. 2 (Juilliard String Quartet)

A Young Rebel

Hindemith at the Yale School of Music

Early during his studies, Hindemith established a reputation as one of Germany’s emerging musical talents. In addition, he was also considered an uncompromising enfant terrible, whose provocative and aggressive musical novelty was designed to outrage German audiences. As he wrote in 1917, “I want to write music, not song forms and sonata forms, to break away from German art music.”

Hindemith was drafted into the army and stationed close to the front line. A scholar writes, “the carnage and devastation of WWI caused a traumatic loss of identification with the pre-war musical values that had been central to Hindemith’s early education.” As Hindemith wrote, “I realized for the first time that music is more than style, technique, and the expression of personal feelings. Music stretched beyond political boundaries, national hatred and the horrors of war. I have never understood so clearly as then what direction music must take.”

Paul Hindemith: Sancta Susanna

Early Notoriety

Hindemith stepped into the limelight with an explosive operatic triptych in 1921. Mörder, Hoffnung der Frauen (Murder, Hope for Women), Das Nusch-Nuschi, and Sancta Susanna use the expressionist notion of shock as a means to articulate oneself. Exploring the relationship between celibacy and lust in Christianity, Sancta Susanna explores the sexual fantasies of a young nun as a nunnery descends into sexual frenzy.

Hindemith gained a reputation as a prodigious but unreflective talent, which “indulged a rather puerile propensity for transgressing bourgeois conventions.” In fact, it would take several decades before Hindemith was allowed to live down the reputation based on these works. However, he was also acknowledged as a leader of the new music, and although the contents of his early operas are unquestionably “horrific, their musical brilliance is equally certain.”

Paul Hindemith: Kammermusik No. 1, Op. 24, No. 1

New Objectivity

The term “Neue Sachlichkeit,” or “New Objectivity,” was coined by the historian and curator Gustav Friedrich Hartlaub. Originally, it referred to a stream in the visual arts that emphasized the democratization of all areas of life. As a movement in Art, it rejected the sentimentality of late Romanticism and the emotional turmoil of expressionism.

Paul Hindemith helped to define this new artistic trend with a series of compositions that combined traditional musical forms, baroque models, and structures with dissonant harmonic writing and jazz-inspired rhythms. It also meant the exploration of various international musical styles, including the music of Béla Bartók, Igor Stravinsky, and Darius Milhaud.

Paul Hindemith: Ragtime for Piano four hands – 1921

Berlin Professorship

In 1927, Hindemith accepted a professorship in composition at the Berlin Music Academy, joining the likes of cellist Emanuel Feuermann, violinist Georg Kulenkampff, and the pianist Artur Schnabel. The Academy was under the direction of Franz Schreker, who initiated classes in the new media of film and radio, and inaugurated the performance of Early Music on original instruments.

Hindemith was particularly critical of Arnold Schoenberg because, according to Hindemith, he was responsible for creating an ever-increasing gap between contemporary composers and the general musical public. As he explained in a public lecture, “The tenuous connection in music today between producers and consumers is to be regretted. The composer today should write only if he knows for what purpose he is writing. The days of composing for the sake of composing are perhaps gone forever. On the other hand, the demand for music is so great that it is urgently necessary for composers and users to come to an understanding of each other.”

Paul Hindemith: Der Lindberghflug (Radio Version) (Ernst Ginsberg, vocals; Betty Mergler, soprano; Erik Wirl, tenor; Fritz Duttbernd, tenor; Gerhard Pechner, vocals; Berlin Radio Choir; Berlin Radio Orchestra; Hermann Scherchen, cond.)

Utility Music

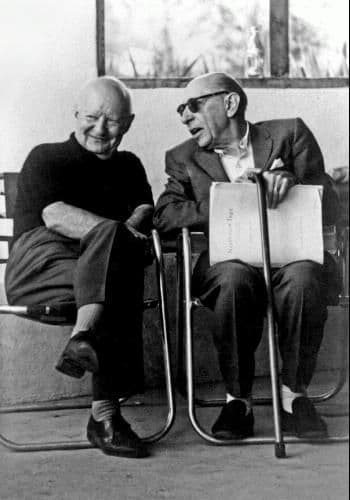

Paul Hindemith and Igor Stravinsky, 1961

For Hindemith, music had to be composed for a special, identifiable purpose. This could be a particular historical event, address an educational need, or even set boulevard news to music. Hindemith’s “Gebrauchsmusik” (Utility Music) contains a diversity of genres, including speaking and acting roles and even audience participation.

Hindemith would retain this compositional aesthetic for the rest of his life. “Gebrauchsmusik” also became a practical and useful tool in calling for World Peace. “It is not impossible,” he writes, “that out of a tremendous movement of amateur community music, a peace movement could spread over the world. People who make music together cannot be enemies, at least not while the music lasts.”

Paul Hindemith: Mathis der Maler (Symphony)

The Case Hindemith

By 1933, only Richard Strauss was held in higher esteem among German composers than Paul Hindemith. On one hand, he was celebrated as the “flag-carrier of the future,” while the threatening voices from the Nazi regime called him a “standard-bearer of decay.” Hindemith was mercilessly attacked by a belligerent press, who branded him a “cultural Bolshevik,” an assessment seconded by Reich Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels.

In October 1936, after a performance of the Violin Sonata in E, a ban was placed on all performances of Hindemith’s works. One year later, Hindemith was the star of an exhibition titled “Degenerate Music,” with an entire section devoted to the “theoretician of atonality” and “closely related to Jews.” Hindemith, steadfast in his moral convictions, decided to leave his native Germany and pursue his career elsewhere.

Paul Hindemith: Violin Sonata in E Major (Frank Peter Zimmermann, violin; Enrico Pace, piano)

Emigration

Hindemith took infinite leave from the Berlin Music Academy and accepted projects in Turkey and the USA. After spending some time in Switzerland, Hindemith reluctantly left for the United States. Previous visits had somewhat disillusioned him, as he had written to his wife, “I’m afraid I shall never really get accustomed to things here.”

In the event, Hindemith secured lectureships at the University of Buffalo, Cornell University, Wells College and eventually Yale University. Hindemith founded the Yale Collegium Musicum, exercising a powerful influence on historically informed performance practice in the United States. His success as a teacher was matched by corresponding success as a composer. Hindemith took American citizenship in January 1946 but returned and settled in Switzerland in 1953.

Paul Hindemith: Clarinet Concerto

Legacy

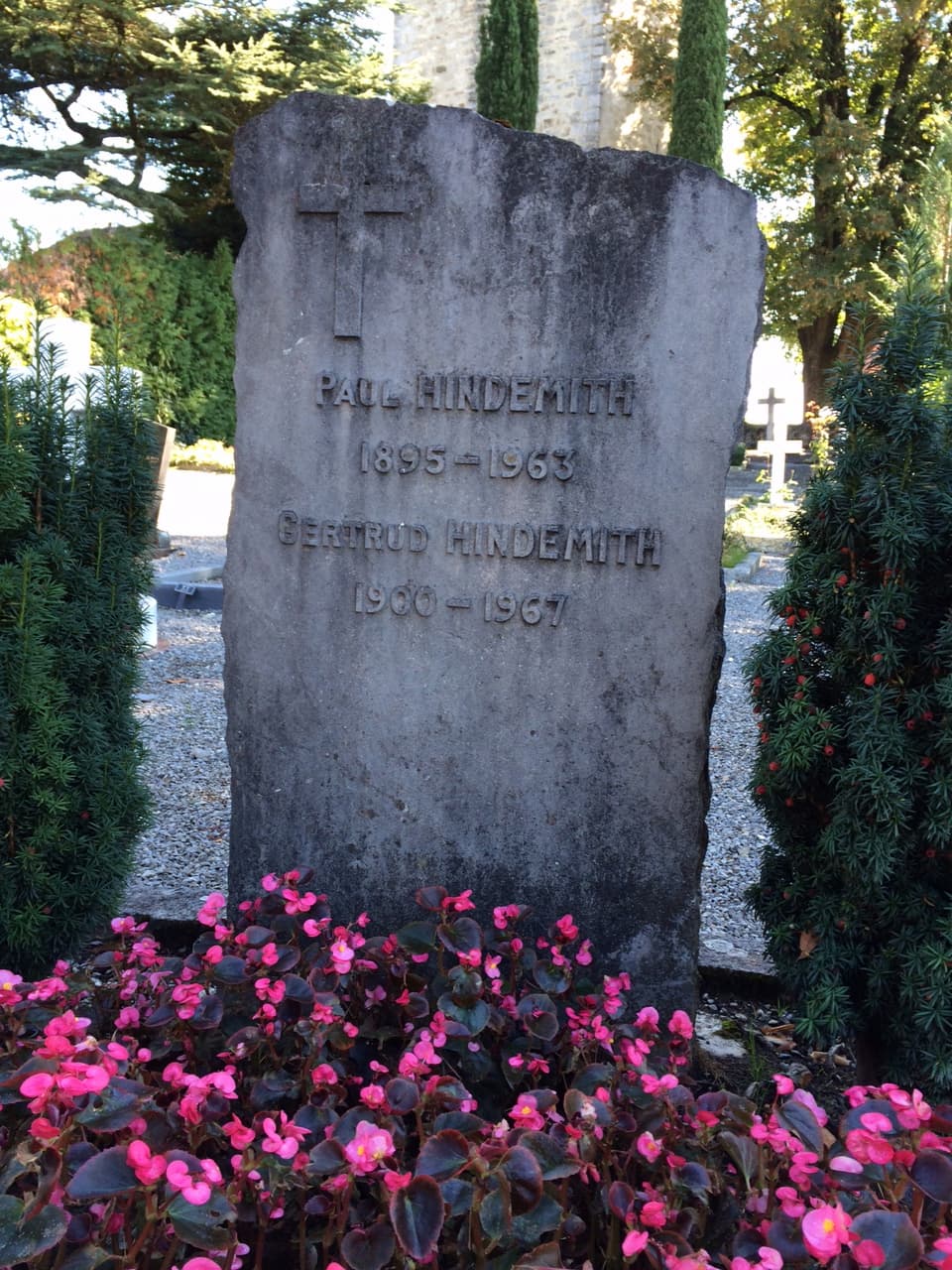

Grave of Hindemith

While greatly admired, Hindemith was not universally acclaimed. Theodor Adorno called his music “symptomatic of a false social consciousness,” and condemned it as “being not truly useful at all.” Hindemith’s final compositions, in turn, represent his embittered rejection of modernity as a tainted ideal. Hindemith was one of the most prolific composers of the 20th century, composing nearly 300 major works.

Yet, as I wrote in the introduction, his music found less public acceptance than those of his contemporaries Stravinsky, Bartók, and Schoenberg. He was uncompromising and highly critical of Schoenberg as a teacher, theorist, and composer and thereby initiated the ongoing discussion of the role of music and the artist in contemporary society. Hindemith always thought of himself as a musician. While he was convinced that composition could not be taught, he strongly “believed that it was the composer’s duty to preserve the cohesion of musical life in all its component parts.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter