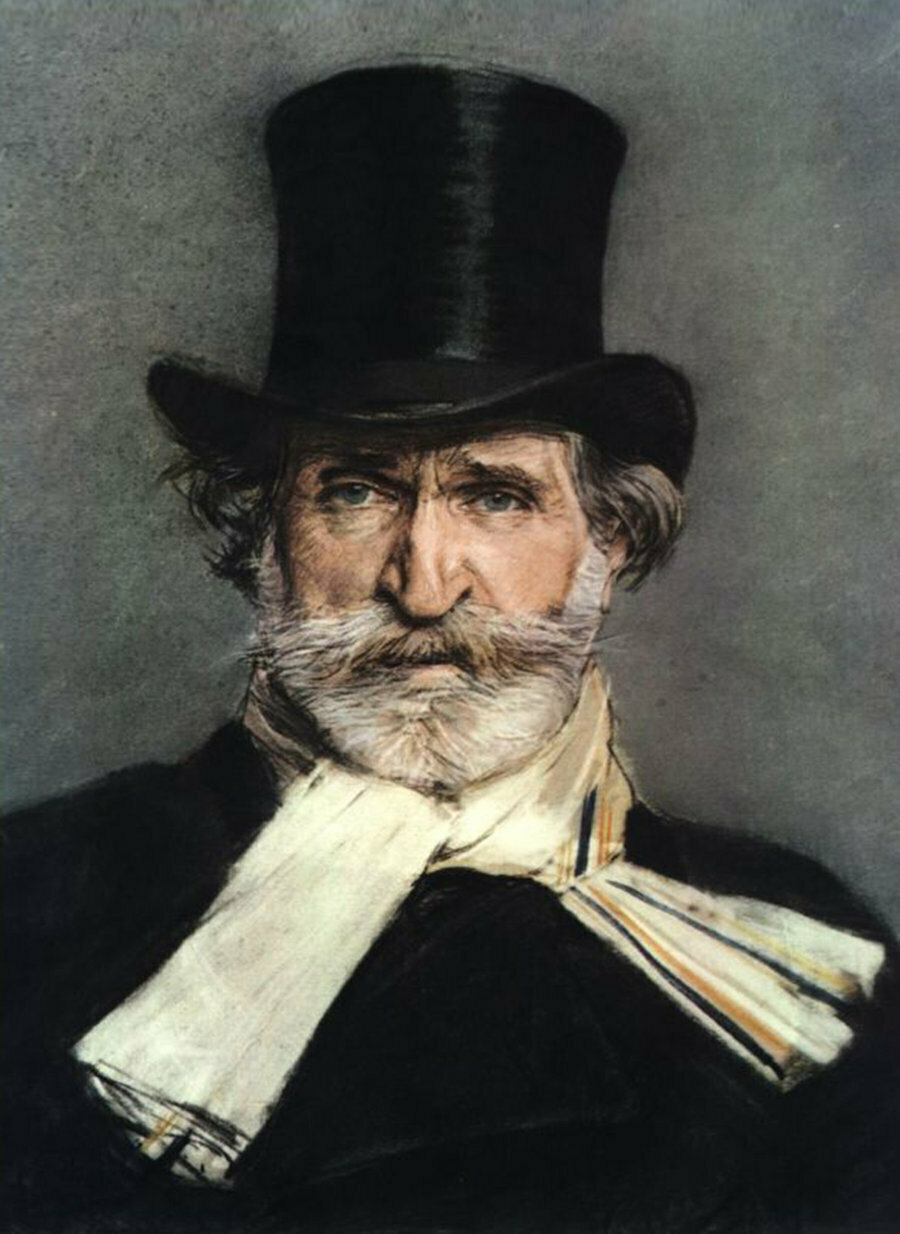

Among the crowning glories of German and Italian opera are The Magic Flute, Tristan and Isolde, La Traviata, Tosca, Norma, and Aida; English opera has Balfe’s “Bohemian Girl” which is barely ever performed, Britten’s “Peter Grimes” whose chief attributes are its interludes, and Purcell’s “Dido and Aeneas” which is famous for the last aria only. Opera in English is very strange then.

Sumi Jo sings “I dreamt I dwelt in marble halls” (The Bohemian Girl)

The Italians have “Nessun dorma”, the Germans have “Liebestod” and the British have “I dreamt I dwelt in marble halls”.

Either we shall have to dredge up old forgotten masterpieces, write new ones- or undertake translation. But operatic translation hasn’t been the happiest of histories.

The favorite way to present foreign-language operas (subtitles are another variation on the same theme) © i.etsystatic.com

In the 19th century, it was quite common to see translated operas. Unfortunately, it was all a bit of a free-for-all. “Cheap” and “quick” were far more valued than “good”. Reading books of the era, complaints keep popping up every now and then.

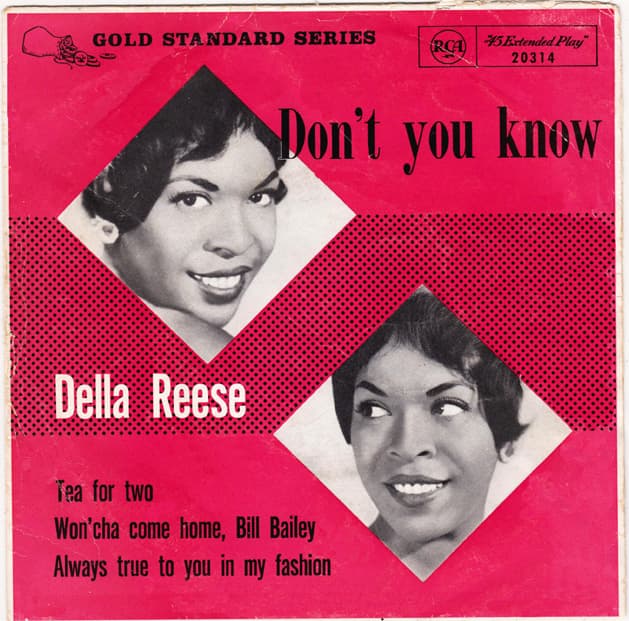

“Don’t You Know” by Della Reese; Puccini brought to the masses, by heavy-handed adulteration © images.45cat.com

Even with the best intentions it can be difficult. Trying to do a literal translation is like trying to fit an armchair into a briefcase, whereas being unfaithful is, being unfaithful. In order to make it work, some middle ground is usually struck; the faithful, but non-literal. They can be awkward, and sound strange to the best of listeners, and ugly to the worst. And in some of the best of scenarios, the beauty of a line may not be its own, but the translator’s.

It has been said that what gives opera vitality as an art form is the union of drama and music. How much of its vitality aside, by translating, you are tampering with that union.

Take Puccini: when in 1959 “Quando me’n vo” [“When I walk/When I walk all alone in the street”] popped up in the charts, it did so as “Don’t you know/I have fallen in love with you”. The sentiment is the same (by coincidence), but about a thousand times less subtle. That is a case in point and of course an extreme one.

The Hungarian State (née Royal) Opera House, where Mahler was director, and gave performances in Hungarian from 1888-1891 © i0.wp.com

That’s enough said against translation- how about for? I can think of no better standard-bearer than Gustav Mahler himself. In 1888 the then 28-year-old Mahler set about turning the Royal Opera House in Budapest from a poorly managed dustbowl into one of the most artistically impeccable in Europe. He sought “the complete integration of drama and music” and partly by having every single opera performed in Hungarian.

Another Conductor with similar ideas, and reputation, was Sir Thomas Beecham. He didn’t go quite as far as Mahler but conducted English translations very often. In the best of his recordings that awkwardness and off-putting novelty melts into sheer ecstasy.

Psalm 13 “Herr, wie lange willst du”, S. 13/2 (Sung in English) : I. “Herr wir lange willst du”…

Sir Thomas Beecham conducting the first movement of Liszt’s “Psalm 13”, where the words are more cutting, in English, than they could ever be in another language.

And complete fidelity is better, but we shall have to put up with seeing them in the half-light, as if through a veil.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Noah Bradley is a young composer and polymath, deeply passionate about the art of music.