The actor Ben Elton once remarked that “artists don’t create society, they reflect it.” In Hong Kong’s swiftly burgeoning opera scene, 2024 bore this out, tracing a journey from the restraint of Mozartian precision to something looser, stranger, and more fantastical. The year’s final offerings—Musica Viva’s La Clemenza di Tito, Opera Hong Kong’s Die Entführung aus dem Serail, and culminating in three late-year productions in rapid succession—illustrated this shift. By December, Hong Kong’s operatic landscape had moved decisively away from the formal, tight-laced classicism of the Enlightenment into the realm of fractured fairy tales and experimental theatre.

Hong Kong Grand Opera: Hansel and Gretel

Hong Kong Grand Opera’s Hansel and Gretel was a long-overdue addition to the city’s repertoire. Performed in English at the Kwai Tsing Theatre, this classic Englebert Humperdinck piece was treated to a production that leaned heavily into the nightmarish aspects of the story. Director Nic Muni reimagined the tale, steering away from its original moral of self-reliance to emphasize its darker undercurrents. The witch’s house—a proper gingerbread house with candy buttons and backgrounded by lurid projections– loomed as a grotesque fantasy, complete with a 3-D projected dragon that was more Tolkien than Brothers Grimm. The father, a burnt and broken figure (performed by a robust though vocally uneven Sammy Chien), and a wan, polio-stricken mother (soprano Nadia Wong) added a layer of bleakness to the narrative.

Hong Kong Grand Opera’s Hansel and Gretel performance

The singing and chemistry between the titular leads anchored the production. Joyce Wong’s Gretel struck just the right balance of innocence and artless charm, complemented by Samantha Chong’s more earnest, bookish Hansel. In addition, their diction was crystal-clear—surtitles were almost unnecessary. The role of the Witch is often sung by a mezzo-soprano (doubling as the Mother); Hong Kong Grand Opera makes a brave but informed decision to cast a tenor in the role of the Witch. Tenor Chen Yong brought a macabre physicality to his performance, transforming from grotesque granny into Chinese mythological ghoul, gnawing on limbs and chewing the scenery with gleeful menace. A well-staged children’s chorus added to the unsettling atmosphere.

While musically solid, the cultural blend in the design felt uneasy. A gnomish Sandman (a light-voiced soprano Kenix Tsang, on her knees), a Dew Fairy (sung with dexterous aplomb by soprano Phoebe Tam) styled as an elderly Chinese martial artist and a Tolkien-esque dragon felt like mismatched puzzle pieces. Moreover, along with the eerie projections of a witch on the watch, the nightmarishness was just a bit too much to bear for some of the younger audience members, who had to leave mid-show. Perhaps it is now time for opera to come with their own set of PG ratings.

The orchestra, under conductor Vivian Ip, recovered from a tentative opening to provide solid support. Ultimately, though uneven, the production succeeded on the strength of Humperdinck’s music, which is truly beautiful, and the delightful performances from the leads.

Hansel and Gretel

Hong Kong Grand Opera

Kwai Tsing Theatre,

22, 23 Dec 2024

*This review was based on the evening performance on November 22nd. In the alternate cast (matinee November 23rd), Gretel is sung by Gloria Chan, Hansel by Kenix Tsang, Father by Jeremy Leung, Mother by Phoebe Tam, Sandman by Samantha Chong, and Dew Fairy by Joyce Wong.

Engelbert Humperdinck: Hansel and Gretel – Overture (Philharmonia Orchestra; Charles Mackerras, cond.)

Ensemble Traversée: Reimagined Bluebeard’s Castle

Ensemble Traversée’s Bluebeard’s Castle was less an opera and more a theatrical meditation, complete with LED panels and a stark stage. Bartók’s psychological exploration of intimacy and isolation was presented as a semi-staged concert at the Cultural Centre Studio Theatre. The singers, Rachel Kwok (Judith) and Lam Kwok-Ho (Bluebeard), performed from tablets while moving through a transverse stage—audience members on either side were made to confront one another, a deliberate choice by the director to heighten the sense of voyeurism and complicity.

The production leaned on abstraction. Fractal projections and shifting coloured lights above created a mood of disorientation, while the singers’ movements—slow and deliberate—added a trance-like quality. Kwok’s light but sweet-voiced Judith created moments of heart-stopping tenderness, while Lam’s saturnine baritone gave Bluebeard the weariness and menace the role demands. Sung entirely in Hungarian, the performance was a testament to the singers’ dedication.

Ensemble Traversée’s Reimagined Bluebeard’s Castle

However, the evening was not without distractions. The amplification, while necessary given the space and vocal fachs available, was occasionally distracting, and a pre-show monologue by the otherwise very capable conductor Vicky Shin felt misplaced, breaking the atmosphere before it had a chance to form. Perhaps an actual narrator with vocal training would have been more up to the task. That said, conceptually this is a solid choice—whereupon vocal coaching would have been advisable.

Still, this was a cohesive and thought-provoking performance of Bartók’s enigmatic Symbolist work: there was a palpable frisson felt in the audience throughout at the sheer beauty of the music which begins and ends in F# (bleeding into C midway when the castle is illuminated), as Judith and Bluebeard are enveloped by utter darkness. Judging from the packed theatre, the Hong Kong public has the taste for it; it is after all music to die for, and hats off to Ensemble Traversee for bringing it to Hong Kong.

Reimagined Bluebeard’s Castle

Ensemble Traversee

Studio Theatre, Cultural Centre,

13,14,15 Dec 2024

*This review was based on the evening performance on Friday, 13th December.

Béla Bartók: Bluebeard’s Castle, BB 62 – Woe! What seest thou? (Cornelia Kallisch, mezzo-soprano; Peter Fried, baritone; Stuttgart Radio Symphony Orchestra; Peter Eötvös, cond.)

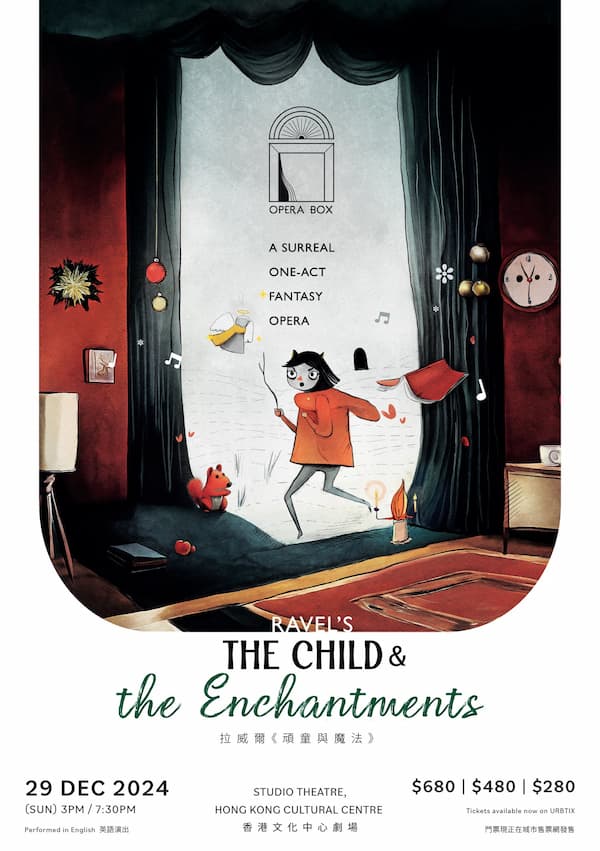

Opera Box: Ravel’s The Child and the Enchantments ( L’Enfant et les Sortilèges)

Opera Box closed the year with an unexpectedly playful and inventive production of Ravel’s L’Enfant et les Sortilèges. Performed in English and staged in a thrust configuration at the Studio Theatre, this production embraced whimsy, reimagining the surreal opera as a Christmas tale. The tree became a Christmas tree, wallpaper shepherds became torn Christmas cards, the Princess became a tree ornament, Santa Claus replaced Old Man Arithmetic, and the ensemble numbers were reworked for a small cast of singers doubling as Santa’s helpers.

The set was beautifully designed, as though scribbled over by a bored child in black and white. Evocative of neo-gothic drawings, with its jagged lines and eerie simplicity, the design heightened the inherent uncanniness in a story of malevolent objects coming alive. A manually operated rotating stage added a frenzied DIY charm.

Despite a few quibbles with diction (tenor Henry Ngan faced the most challenges in his rapid-fire arias as Clock and Old Man), the cast was vocally strong. Dennis Lau (Teapot) and Samantha Chong (Teacup) played off each other with verve, their flirtation laced with humour. Vivian Yau’s agile soprano soared equally in both Fire and the more pensive roles of Princess and Nightingale, while mezzo-soprano Jeannette Lee as the Child brought a rare stillness and depth to her climactic “You the heart of the rose.” Finally, the singers’ dynamic use of the space—popping up in unexpected places—kept the audience engaged in the fever dream-like progression of the story. Some truly delightful moments included the Frogs’ chorus, with actual wind-up frogs pattering all over the floor (at the feet of some of the occupants of front-row seats!), toy-puppetry, and the discordant croaking and miaowing of different animals (surprisingly, performed as written).

Opera Box: Ravel’s The Child and the Enchantments ( L’Enfant et les Sortilèges)

There were some hiccups in the staging; after all, the Studio Theatre is not a venue used for opera. The narrow aisles provided some nail-biting moments for some of the exits and entrances, and some of the acoustics were uneven, perhaps exacerbated by conductor Isaac Droscha’s eccentric positioning with his back to the singers. However, it would be churlish to expect a proscenium-stage experience in a proper opera house in a Black Box production; the cast, one feels, did their level best with the spatial limitations.

While the reduced orchestration and English translation did strip away some of Ravel’s lushness and Colette’s wit, the production’s energy and inventiveness more than compensated. Opera Box brought theatricality to the fore, offering a joyous and imaginative conclusion to the year.

Ravel’s The Child and the Enchantments

Opera Box

Studio Theatre, Cultural Centre,

(15:00, 19:30)

29th Dec 2024

*This review was based on the evening performance. Singers featured were Jeannette Lee (mezzo-soprano) as The Child, Samantha Chong (mezzo-soprano) as Mother, Teacup and Dragonfly, Henry Ngan (tenor) as Clock and Old Man, Amanda Ng(soprano) as New Armchair, Shepherdess and Owl, Lam Kwok-Ho(baritone) as Old Armchair, Male Cat and Tree, Dennis Lau(tenor) as Teapot and Frog, Vivian Yau(soprano) as Fire, Princess and Nightingale, Jessica Ng (soprano) as Bat, and Phoebe Tam(soprano) as White Cat and Squirrel.

Maurice Ravel: L’enfant et les sortileges – Arriere! Je rechauffe les bons (Cassandre Prevost, soprano; Julie Boulianne, mezzo-soprano; Nashville Symphony Orchestra; Alastair Willis, cond.)

Sylvia Woo is a writer based in Hong Kong. She is also an avid opera and theatre lover.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter