Soon after the successful première of Giuseppe Verdi’s first opera Oberto, Bartolomeo Merelli, the impresario at La Scala commissioned three further operas. The comic opera Un giorno di regno was a disastrous failure, and contemporary critics considered the question of Verdi’s personal musical style. “The crescendo and the use, not abuse, of unison, had been suggested by Donizetti; the form of the cabaletta, in which the phrase leaps and starts, rather than flows, by Federico Ricci; the employment of syncopation by Signor Pacini, and the excess of appoggiatura by Bellini.”

The Inspiration

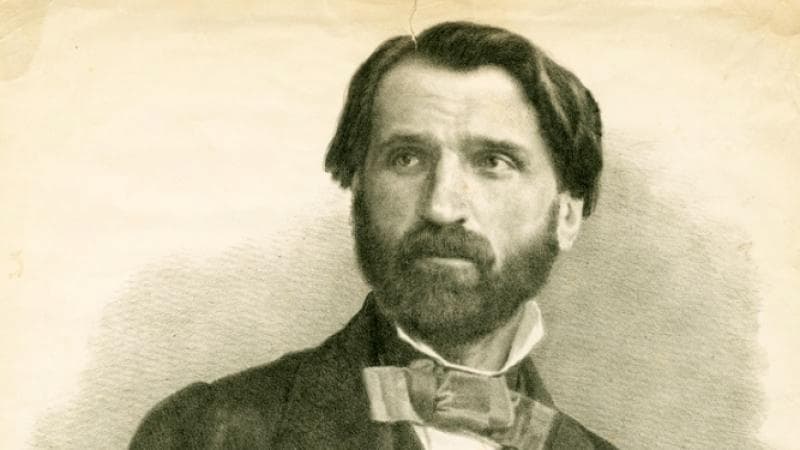

Giuseppe Verdi, 1842

While we get a glimpse into the incredibly rich and varied Milanese musical landscape that Verdi experienced during his formative years, the composer was decidedly unsure of how to continue on his compositional path. However, during the winter of 1840-41 Verdi stumbled upon Temistocle Solera’s libretto of Nabucco. The composer remembers, “I got home and with an almost violent gesture threw the manuscript on the table… The book had opened in falling… Without knowing how, I gazed at the page that laid before me, and read the line: Va, pensiero, sull’ali dorate. I ran through the lines that followed and was much moved, all the more because they were almost a paraphrase from the Bible, the reading of which had always delighted me. I read one passage, then another…”

Giuseppe Verdi: Nabucco, “Va pensiero”

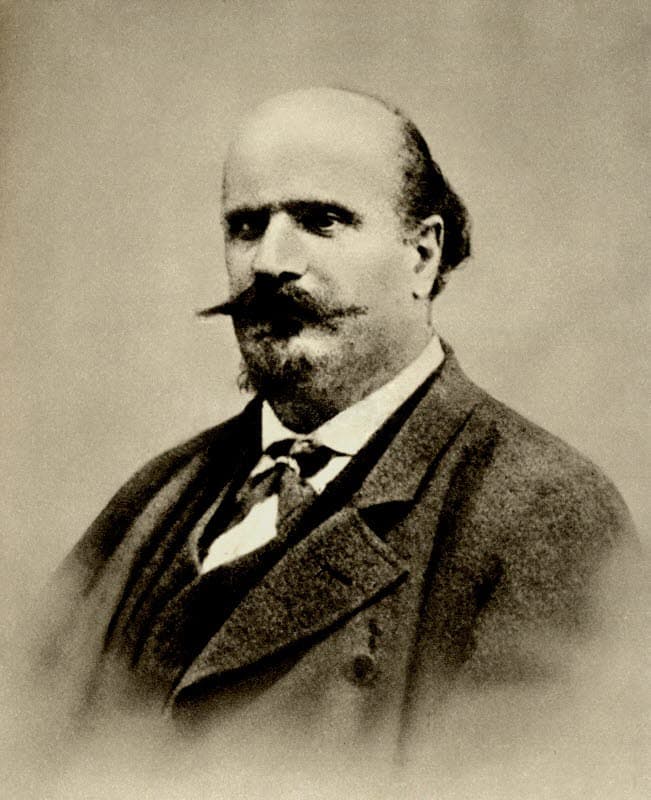

Temistocle Solera

In an instant, Verdi felt compelled to set to music the dramatic conflict of the Hebrew slaves and their Babylonian captors. The vast majority of the score was written in the spring and summer of 1841, and by the autumn the work was complete. “Nabucodonosor,” as it was called before a revival in Corfu, was scheduled for 9 March 1842. Contemporaries report that the production was “makeshift, with scenery and costumes resurrected from a ballet on the same subject given four yours earlier.” To make matters worse, Giuseppina Strepponi, the soprano lead, was in poor voice, and Donizetti wrote “not even Verdi wants her in his opera.” Strepponi did sing in the premier on 9 March 1842, but her final scene was cut after two performances. Be that as it may, the opera was a great success. In particular, the famous “Va, pensiero” chorus sung in the third act by the Hebrew slaves seemingly became the focal point for audience enthusiasm. Eager nationalists and scholars “long believed that the audience, responding with nationalistic fervour to the powerful hymn of slaves longing for their homeland, demanded an encore of the piece.”

Giuseppe Verdi: Nabucco – Act IV, Scene 2 Finale, “Immenso Jeovha” (Cornell MacNeil, baritone; Metropolitan Opera Orchestra; Thomas Schippers, cond.)

Public Reception

Giuseppina Strepponi

Contemporary audiences did indeed demand an encore, but it was not for “Va, pensiero,” but rather for the hymn “Immenso Jehova,” sung by the Hebrew slaves in Act 4 thanking God for saving His people. As such, “Va, pensiero” was probably not the national anthem of the Risorgimento, even though it was performed at Verdi’s funeral under Toscanini with a chorus of 820 singers. Not everybody was enthused, however. The Prussian composer Otto Nicolai wrote, “Verdi’s opera are really horrible. He scores like a fool, technically he is not even professional, and he must have the heart of a donkey and in my view he is a pitiful, despicable composer… Nabucco is nothing but rage, invective, bloodshed and murder.” This rather devastating assessment appears to have been a case of sour grapes. Nicolai had been working in Italy and he was first offered the libretto for Nabucco, but he turned it down. Instead he composed Il proscritto, a libretto that Verdi had rejected. In the event, Il proscritto bombed disastrously and Nicolai was forced to return to Germany.

Giuseppe Verdi: Nabucco, “Ben io t’ivenni” (Maria Callas, soprano; Orchestra del Teatro San Carlo di Napoli; Vittorio Gui, cond.)

Giuseppe Verdi: Nabucco, “Anch’io dischiuso un giorno” (Maria Callas, soprano; Orchestra del Teatro San Carlo di Napoli; Vittorio Gui, cond.)

Verdi: “Nabucco was the true beginning of my artistic career.”

Verdi’s Nabucco performed at the MET

For Verdi, as the composer himself wrote, “Nabucco was the true beginning of my artistic career.” The work signalled the true emergence of his distinctive voice. A scholar writes, “It is admittedly an uneven score, with occasional lapses into banality and some unsteady formal experiments that we shall rarely see in future works. But the essential ingredients of Verdi’s early style are in place: a new and dynamic use of the chorus, an extraordinary rhythmic vitality and, above all, an acute sense of dramatic pacing.”

We should not forget, however, that Nabucco was born during a period of deep personal crisis. Amidst persistent health problems and financial insecurity, “a terrible disease, perhaps unknown to the doctors, took the life of his first child, Virginia Maria Luiga.” One year later, on 22 October 1839, Verdi’s son Icilio Romano fell ill, and despite immediate medical intervention suddenly died. The hand of fate knocked a third time in May 1840, when Verdi’s wife Margherita contracted encephalitis and died at the age of 26. Verdi was devastated and later recalled, “A third coffin goes out of my house. I was alone! Alone!” In fact, Verdi renounced composition and Nabucco only appeared some 18 months later.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Giuseppe Verdi: Nabucco, “Io t’amava”