For a good many opera lovers around the world, Puccini’s passionate, timeless, and indelible story of love among young artists in Paris is the world’s most popular opera. Indeed, La Bohème “is the definitive depiction of the joys and sorrows of love and love, but on closer inspection, it also reveals the deep emotional significance hidden in the trivial things that make up our everyday lives.”

Ruggero Leoncavallo: La Bohème

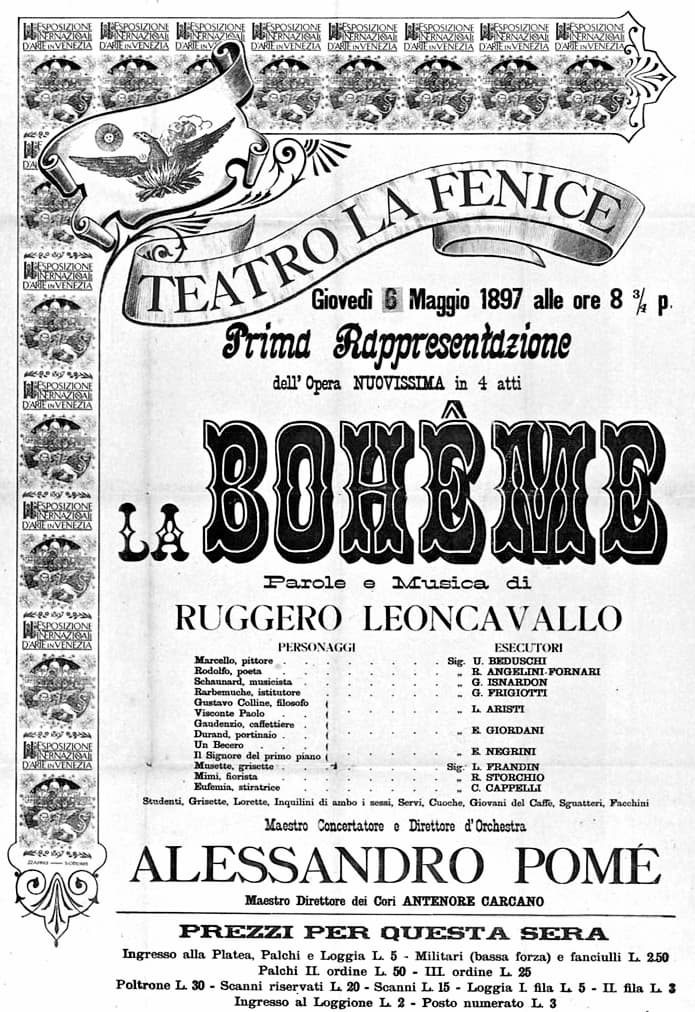

What is probably less well known is the fact that Ruggero Leoncavallo (1857-1919), whose name is universally connected to Pagliacci, composed his own La Bohème. That work premiered at the Teatro la Fenice in Venice on 6 May 1897, roughly one year after Puccini presented his setting at the Teatro Regio in Turin. Both librettos are based on the novel Scènes de la vie de bohème, originally published in serial form by Henri Murger in 1851, who subsequently turned these loose stories into a coherent play. A scholar writes, “there is some recent evidence to suggest that the scenario on which both operas are based was probably Leoncavallo’s.”

Francesca Manzo Sings Leoncavallo’s La Bohème, “Musette Svaria”

The Conflict of Authorship Between Puccini and Leoncavallo

La Bohème by Ruggero Leoncavallo

Since Puccini and Leoncavallo worked on their respective works at the same time, it was almost inevitable that a conflict of authorship would arise. Leoncavallo claimed that he had previously offered Puccini a completed libretto. As such, Leoncavallo claimed precedence over the subject. In addition, he asserted Puccini knew all along that he was working on the opera. Puccini responded to the accusation the following day in an open letter to Il corriere della sera, claiming that he had been working on his own version for some time, and felt that he could not oblige Leoncavallo by discontinuing the opera. He also “welcomed the prospect of competing with his rival and allowing the public to judge the winner.” A musicologist writes, “A mutual influence was certainly exercised by the assumption each composer made about his adversary’s libretto and musical style. The deletion of the ‘atto del cortile’ from Puccini’s opera may be seen as a direct consequence of his acquaintance with Leoncavallo’s libretto, whereas Leoncavallo, in the later version of his opera entitled Mimì Pinson, tried to adopt the inverse order of vocal roles, which by that time had been accepted by Puccini’s public.”

Ruggero Leoncavallo: La Bohème – Act I: No, signor mio, così non puo durare (Friedrich Lenz, tenor; Alan Titus, baritone; Bernd Weiki, baritone; Franco Bonisolli, tenor; Sofia Lis, mezzo-soprano; Raimund Grumbach, baritone; Lucia Popp, soprano; Bavarian Radio Chorus; Munich Radio Orchestra; Heinz Wallberg, cond.)

Ruggero Leoncavallo: La Bohème – Act I: O Musette (Franco Bonisolli, tenor; Alexandrina Milcheva, mezzo-soprano; Alan Titus, baritone; Friedrich Lenz, tenor; Alexander Malta, bass; Munich Radio Orchestra; Heinz Wallberg, cond.)

A Comparison: The Dramatic and Musical Differences

Ruggero Leoncavallo: La Bohème, 1899

A comparison of both works reveals interesting dramatic and musical differences. Leoncavallo adhered closer to Murger’s novel, “disclosed by literary and musical quotations which permeate his libretto and score.” It has been suggested that Leoncavallo approached the work with the realism demanded from verismo opera. In Puccini’s opera it remains unclear, which of the four Bohemian friends is the musician, whereas Leoncavallo immediately identifies Schaunard as the composer. He performs his own composition; a cantata parody in Act 2, accompanying himself on the piano while the orchestra remains silent.

“For one moment the listener has the illusion of being at a party rather than at the opera.” In general, stage music plays a greater role as part of the action in Leoncavallo’s setting, as “he conceives this music as being part of an outside reality grafted onto his work.” And while Puccini balances the contrast between joyous and serious moments and their musical accompaniments in all four acts, Leoncavallo introduces a complete break at the beginning of Act 3. The first two acts are comic opera depicting Bohemian life, while acts 3 and 4 “unmask the carefree exuberance of the first two acts a main affect and unreal. The comedy is but a façade.”

Ruggero Leoncavallo: La Bohème – Act II: Inno Della Bohème (Lucia Mazzaria, soprano; Jonathan Summers, baritone; Martha Senn, mezzo-soprano; Mario Malagnini, tenor; Bruno Praticò, baritone; Silvano Pagliuca, bass; Pietro Spagnoli, baritone; Romano Emili, tenor; Giampaolo Grazioli, tenor; Cinzia de Mola, mezzo-soprano; Teatro la Fenice Chorus; Teatro la Fenice Orchestra; Jan Latham-König, cond.)

Ruggero Leoncavallo: La Bohème – Act II: Da Quel Suon Soavemente (Lucia Mazzaria, soprano; Jonathan Summers, baritone; Martha Senn, mezzo-soprano; Bruno Praticò, baritone; Silvano Pagliuca, bass; Pietro Spagnoli, baritone; Cinzia de Mola, mezzo-soprano; Teatro la Fenice Chorus; Teatro la Fenice Orchestra; Jan Latham-König, cond.)

Ruggero Leoncavallo: La Bohème – Act II: Ma Quando Smettete? (Lucia Mazzaria, soprano; Jonathan Summers, baritone; Bruno Praticò, baritone; Silvano Pagliuca, bass; Pietro Spagnoli, baritone; Romano Emili, tenor; Giampaolo Grazioli, tenor; Teatro la Fenice Chorus; Teatro la Fenice Orchestra; Jan Latham-König, cond.)

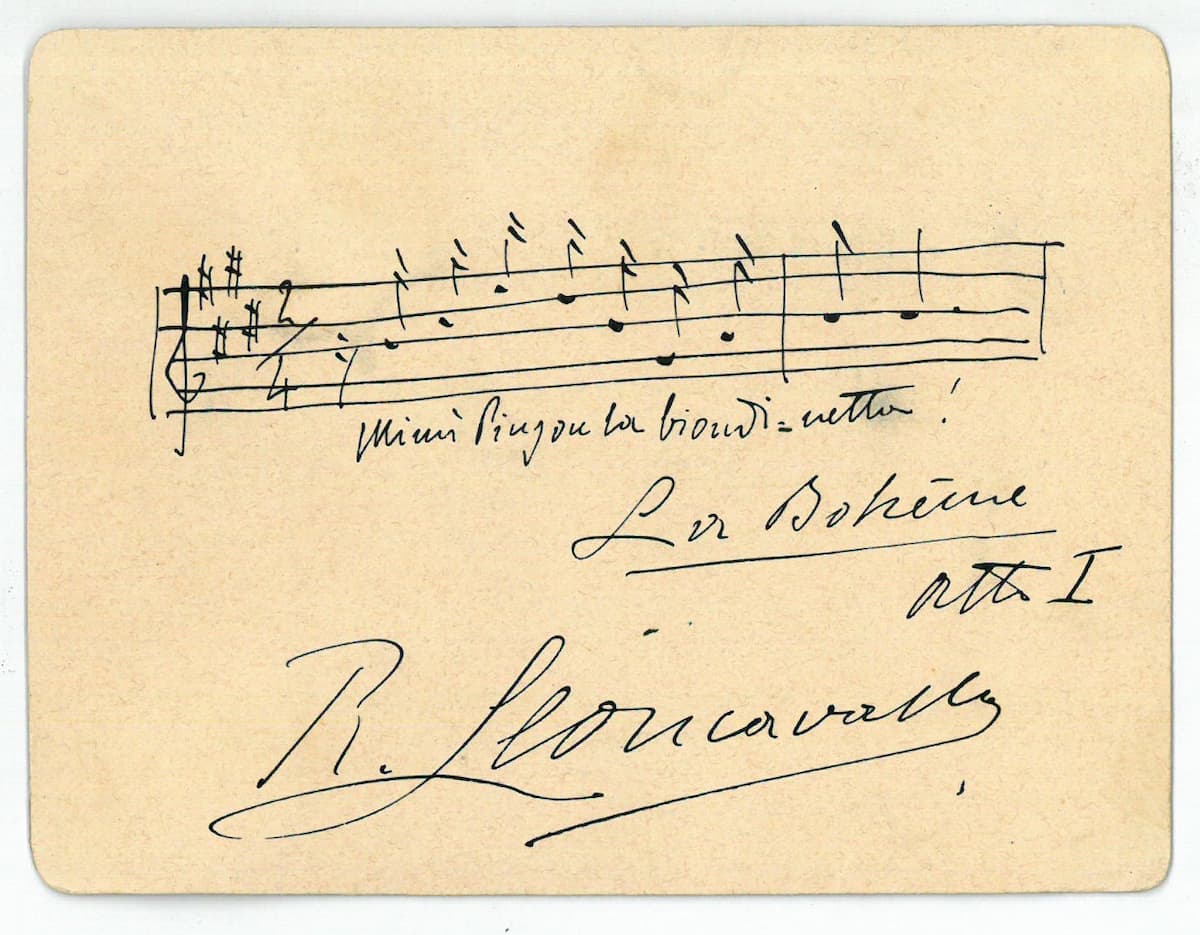

Ruggero Leoncavallo’s quotation of a melody from La Bohème

We might also take a quick look at how Leoncavallo, compared to Puccini, deals with Mimi’s illness. For Puccini, Mimi is ill right from the beginning, and illness is an integral part of her personality. As listeners, we always have the suspicion that her illness is the primary reason why Rodolfo falls in love with her. To be sure, the sense of poverty in Mimi’s life is “not unconnected with her illness, but the dominating impression is of a fatality.” In Leoncavallo’s setting, Mimi falls ill during the action as the unmistakable result of her circumstances.

“With no money, she is prematurely discharged from the hospital, and her death is no more than the natural consequence of a medical system perverted by capitalism. Sorrow at her death is mingled with anger at the horrid conditions that caused it.” After the highly successful première of Leoncavallo’s La Bohème, both works coexisted for a decade but Leoncavallo’s work proved less attractive to a broader public. The “impact of Puccini’s musico-dramatic vision and the superiority of his musical invention eventually made history decide against Leoncavallo.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Mario del Monaco Sings Leoncavallo’s La Bohème, “Testa adorata”

Interesting, but the claim that Puccini does not make clear who is the composer is erroneous. Schaunard’s opening story tells us how he has just come by some more et very clearly. “Un inglese , un Signor, vuole un musicista”.