Francis Poulenc: La voix humaine

Francis Poulenc, 1958

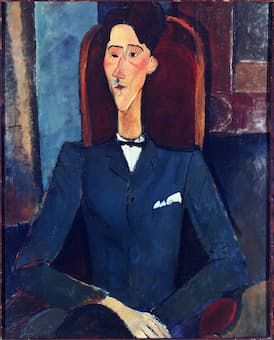

In the early 1920’s, Jean Cocteau (1889-1963) had been the unofficial spokesman for a group of six composers emphasizing directness, simplicity, clarity and humor. “Les Six,” comprising George Auric, Louis Durey, Arthur Honegger, Darius Milhaud, Francis Poulenc and Germaine Tailleferre, made their debut with music for Cocteau’s play The Marriage on the Eiffel Tower, which vacillated between irreverence and incomprehensibility.

Jean Cocteau

Francis Poulenc and Jean Cocteau had remained friends, but by 1958 they had not artistically collaborated in almost thirty years. It was then that a publisher approached Poulenc with the play “La Voix Humaine,” originally written by Cocteau in 1928. Cocteau had always been criticized for writing plays that did not give actors enough opportunities to display their acting skills. As such, Cocteau decided to create a play that required the actress not only to portray the emotion behind her lines, but also depict reactions to a voice, which the audience cannot hear. His vision was to create a one-woman play with the character making a final phone call to the man who kept her as a mistress. Her ex-lover is getting married the next day, leaving the woman alone, distraught, and suicidal.

La Voix Humaine by Cocteau and Poulenc

Cocteau had written “La Voix Humaine” in 1928, shortly before being admitted into a rehabilitation center for opium addiction. The staged play received mixed reviews, and 17 years later Cocteau agreed to work with Roberto Rossellini on a film version. Poulenc had known the play in the late 1920s, but waited many years before setting it to music because he felt “that he needed a great deal of experience to perfectly construct such a work.” Poulenc was looking to compose a score that emotionally spoke to the audience while at the same time retaining the substance of the play. Above all, the score had to portray the pain of the heroine so that the audience would be able to sympathize with Elle’s emotions. He carefully adapted Cocteau’s text and omitting only those passages that he believed would reduce the emotional tension of the opera. “Many themes of Cocteau’s play resonated with Poulenc, such as the sleeping pills, the specter of suicide, and the love for a dog, even if he was not living through the kind of rejection Elle experienced.”

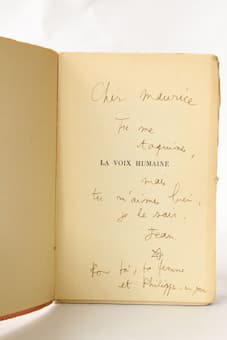

La Voix Humaine by Cocteau and Poulenc,

1930 edition with autograph

Poulenc knew all about the nature of fear, depression and nervous exhaustion, obsession and rejection the loss of a lover can engender. “I’m writing an opera,” he disclosed to a friend, “you know what it’s about: a woman (me) is making a last telephone call to her lover who is getting married the next day.” Poulenc had recently lost one lover and was enduring an enforced separation from another whom, he felt sure, “life will inevitably take away from me in one way or another.” As always, Cocteau was hands on in the process, and shared his ideas on the costumes, sets, and transitional changes due to omission of text. Poulenc finished the vocal score on 7 August 1958 and immediately started working on the orchestrations, which was completed on 19 September of the same year. Several opera houses were vying to stage the premiere, which was eventually given at the Opéra Comique in Paris on 6 February 1959, with a repeat performance presented at La Piccola in Milan on 18 February. The opera met with immediate success and went on for performances at La Scala in Milan, as well as in Portugal, Britain, and the United States.

La Voix Humaine performed by Denise Duval

A scholar writes, “La Voix Humaine is a curious, uncomfortable work which does not fit securely within the traditional boundaries of opera or play… It is a work revealing the inner thoughts, emotions, and private struggles of its creators; sentiments never intended to be completely evident to the audience. This is private music, for the in-crowd. For those able to appreciate its subtleties, it is a work of genius, revealing naked emotions rarely exhibited on the stage with such realism.” This sense of “naked realism” is the immediate result of Poulenc rejecting operatic lyricism in favor of a fragmentary, declamatory approach to the voice. By providing the voice with a recitative-like style, he not only retained the natural inflections of speech, but through frequent pauses and silences, imitates a telephone conversation as well. When Cocteau wrote his play in 1928, the telephone was the height of communication technology. Thirty years later, Poulenc had to assess the telephone’s place in 1950s society. As such, Poulenc had to reexamine the anxiety of technological dehumanization, with the orchestra taking the role of the ex-lover, communicating what is said on the other end of the line. Once we fast-forward to 2022, we understand that the technical aspects of communications have fundamentally changed, as is suggested by the featured performance by Barbara Hannigan. The concentrated emotional and psychological anguish portrayed by Poulenc and Cocteau, however, will remain timeless.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter