Political stirrings of national identity and pride ignited a great awakening across Europe in 1848. Urging an end to Habsburg absolutist rule, the Czech composer Bedřich Smetana (1824-1884) openly participated in this revolution. Barely escaping arrest, and unable to establish a career in Prague, Smetana left for Sweden.

Bedřich Smetana

He proudly proclaimed “I am Czech in body and soul,“ yet was unable to express himself in what was supposedly his native tongue. Educated in German, like most of his generation of Czechs, he enthusiastically envisioned opera and symphonic works based on themes from Czech history and mythology. The years in Swedish exile helped to ferment his development as a composer, and stirred by the rhythms and melodies of Czech folk music, Smetana envisioned a new and unique poetic language. As the Habsburg Empire gradually weakened, a more enlightened atmosphere emerged in Prague, and by 1861 Smetana was seeing prospects of a better future for Czech nationalism and culture.

Bedřich Smetana: The Bartered Bride, “Overture”

Smetana’s comic opera The Bartered Bride, with a libretto by Karel Sabina, was first performed at the Prague Provisional Theatre on 30 May 1866. The idea of building a National Theatre that would celebrate the autonomy of a unique Czech nation was first proposed in 1844. A number of patriots in Prague requested “the privilege of constructing, furnishing, maintaining and managing an independent Czech theatre.”

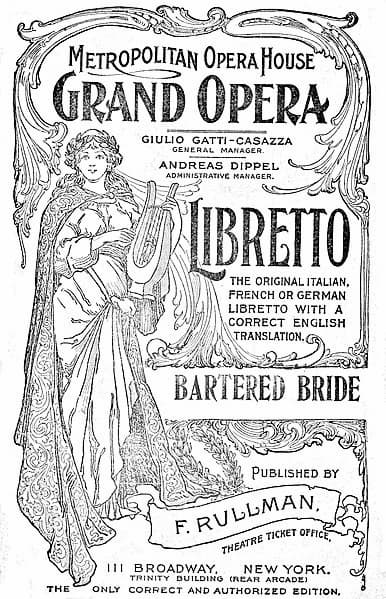

Smetana’s The Bartered Bride libretto cover

The Provincial Committee of the Czech Assembly granted that privilege, but the collection of funds for the purchase of land only started six years later. A magnificent location on the bank of the river Vlatava with a view of Prague Castle was eventually purchased, but the initially grand designs could not be realized. Instead, a rather modest provision building, “The Provisional Theatre” opened its doors on 18 November 1862. This temporary structure did eventually become a constituent part of the final version of the “National Theatre.”

Bedřich Smetana: The Bartered Bride, “Polka”

Jan Nepomuk Maýr was appointed first music director of the Provisional Theatre in the autumn of 1862. Smetana himself had hoped for the appointment, but his reputation went against him. He was known as a follower of Liszt and Wagner, and his support of the “Young Czech Party” brought him into direct conflict with the intendant-elect of the Provisional Theatre.

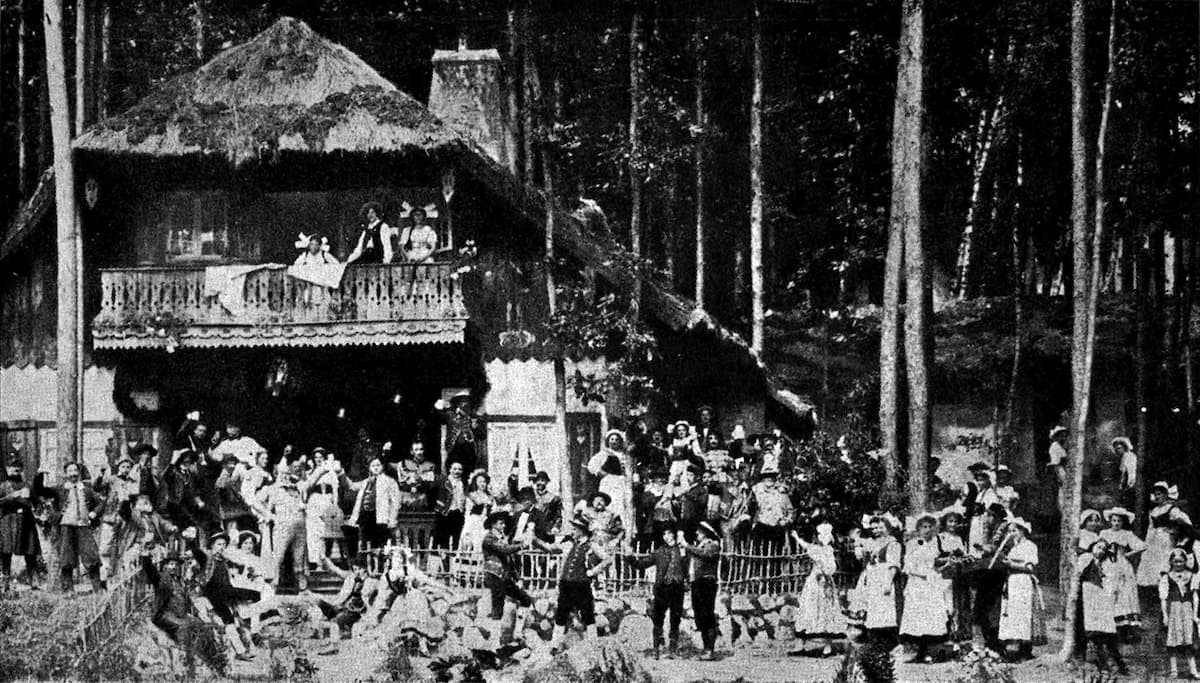

Smetana’s The Bartered Bride Open-air performance at Zoppsot, near Danzig

The Theatre opened its doors on 18 November 1862 with a performance of Vítězslav Hálek’s tragic drama King Vukašín. And since no suitable Czech opera could be found, the first opera performed at the theatre, on 20 November 1862, was Cherubini’s Les deux journées. Smetana was stung by having been rejected as music director, but “most of all he regretted that the theatre on which he had set his heart should have begun to function on the basis of mediocrity and convention.” However, he was soon elected President of the “Society for Czech Artists,” and Smetana made it his goal to “sharply attack the deficiencies of music around him.”

Bedřich Smetana: The Bartered Bride, “March of Comedians”

The primary target of Smetana’s criticism was directed against Maýr, who favoured Italian opera. Maýr retaliated and refused to conduct Smetana’s three-act opera The Brandenburgers in Bohemia. However, Smetana eventually convinced the board that a more balanced repertoire, alternating Italian, German and French operas with Slavonic and Czech works, should be the way forward. Maýr was removed in 1866 and replaced by Smetana, but the rivalry continued unabated. However, various efforts to remove Smetana from his post, and to reinstate Maýr, were unsuccessful. Smetana’s Bartered Bride was not immediately successful, but after extensive revisions over four years, it was widely regarded as a major contribution towards the development of Czech opera and music.

Bedřich Smetana: The Bartered Bride, “Furiant” (Skočná)

Set in a country village with realistic characters, it is a joyous celebration of Czech culture and identity, and the distinct rhythmic inflections of the Czech language and of Czech folk dances combine irresistibly. The composer said he was trying to give the music “a popular character because the plot was taken from village life and demanded a national treatment.”

Title page of the libretto of Smetana’s The Bartered Bride (Metropolitan Opera House, 1908)

In doing so, he rhythmically referenced the characteristic folk dances of Bohemia—the polka, the skočná and the furiant. Smetana provides only occasional glimpses of authentic Czech folk melodies, and the habitual emphasis on the authenticity of the setting and costumes in productions is primarily a matter of staging. Nevertheless, Smetana “clearly felt the pulse of peasantry” and the simplicity of the music not only connected to a broad folk base, but it proved highly inspirational to the emerging independence movement.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter