For well over 20 years, Johannes Brahms (1833-1896) seriously considered writing an opera. In 1869, encouraged by the conductor Hermann Levi and the engraver Julius Allgeyer, Brahms initially contemplated, more or less seriously, operatic settings of Méhul’s Uthal, the heroic tale of Ritter Bayard, and even Wolfram von Eschenbach’s Parzival. Yet somewhat surprisingly, the singular operatic subject that kept Brahms interested for an extended period of time was the fairy tale “The Stag King” by the Venetian playwright Carlo Gozzi. Allgeyer presented the composer with a libretto draft, as did the Nobel Prize winner Paul Ludwig von Heyse. Clearly, his friends expected Brahms to create an independent and original operatic genre, located between the traditional operatic style and the musical dramas of Richard Wagner. In the end, Brahms disappointed them all, yet glimpses of his operatic conception do surface in the Alto Rhapsody, premiered in Jena on 3 March 1870.

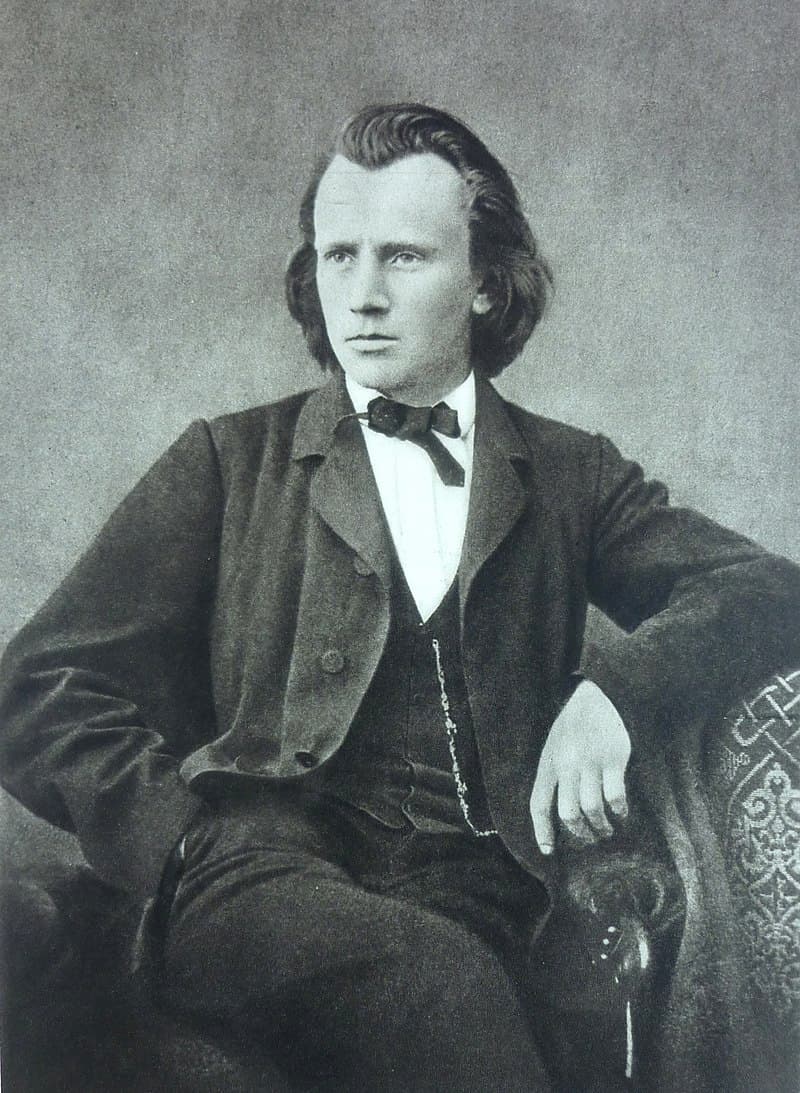

Johannes Brahms, 1866

For his setting, which may or may not have been a wedding gift for Clara Schumann’s daughter Julie, Brahms selected three stanzas from Wolfgang von Goethe’s Harzreise im Winter (Harz Mountain Journey in Winter).

But who is that apart?

His path disappears in the bushes;

behind him the branches spring together;

the grass stands up again;

the wasteland engulfs him.

Ah, who heals the pains

of him for whom balsam turned to poison?

Who drank hatred of man

from the abundance of love?

First scorned, now a scorner,

he secretly feeds on

his own merit,

in unsatisfying egotism.

If there is on your psaltery,

Father of love, one note

his ear can hear,

then refresh his heart!

Open his clouded gaze

to the thousand springs

next to him who thirsts

in the wilderness!

Julie Schumann, 1868

The three stanzas selected by Brahms correspond exactly with the stanzas Goethe quoted in his account of the Harz Mountain Journey. Goethe writes, “Having reached daylight again, I wrote some essential notes, yet at the same time wrote with an entirely fresh sense the first stanzas of the poem, which has attracted the attention of many friends up to now. Thus might the stanzas, which concerned the strange man soon to be encountered, find a place here, since more than many words they are appropriate to express the loving state of my inner self at that time.”

The melancholic persona as the central image of the poem was actually one of Goethe’s close friends, who had asked for help during periods of intense depression and despair. Goethe sets a grandiose stage, contrasting bleak and wild aspects. “The gloom of a dense wall is contrasted by the mountain summit as a metaphoric altar; a drenching storm; a predatory bird soaring; the themes of pilgrimage, loneliness, balsam turned to gall, as love received and transmuted into poison in the dark recesses of an estranged human consciousness.” As a scholar writes, the themes of alienation and individual human redemption are reflected powerfully in Brahms’ setting. In them, Goethe, as Brahms through Goethe, speaks pertinently to the dilemma of humankind.

Formally, Brahms produced a three-part structure, in which a da-capo aria and a final chorus follow an introductory recitative. The recitative is setting the scene, introduces us to the figure depicted, and asks the question of who is the straying figure. In the aria, we learn about the figure’s plight and feelings and the implications of his need, and the concluding chorus is seeking redemption, reconciliation, and the motivation of spirit.

Harz Mountain

The orchestra aimlessly traces a desolate winter landscape in which the grief-stricken young man is searching for solitude. His mental anguish and distress are encapsulated within the opening recitative. Dark, uncompromising, and graphic in its description of emotional oppression, it undoubtedly represents the most operatic passage Brahms ever published. Increasing in tempo and agitation, the ensuing da-capo aria evokes the mental bewilderment of the protagonist, musically depicted by Brahms’s incessant use of cross-rhythms. Finally, the music turns to the major key, and a male chorus provides the warm harmonies to accompany a hymn-like melody. Religious form and gesture are used to alleviate the sentiment of personal despair, and the concluding words “erquicke sein Herz” (refresh his heart) are repeated in the manner of an Amen.

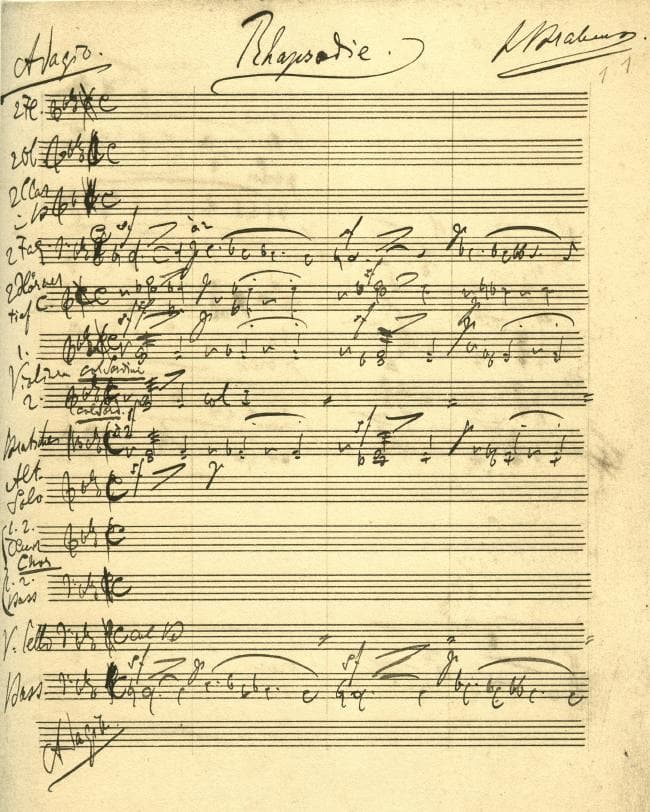

Brahms’ Alto Rhapsody

A scholar writes, “The Alto Rhapsody is a work of compelling structural logic within purely musical elements.” Brahms’ setting is a deeply illuminating interpretation of Goethe’s poem, “by explicit or subtly suggestive literary allusions within its rich musical substance. Indeed, Brahms’ music, far from constituting a pallid echo of Goethe’s text, profoundly enhances textual meaning and intensity of statement in the poem to which it is allied in consistently opposite, con-significant structures.” When Brahms sent the finished score to Clara Schumann for her approval, she recorded in her diary, “It is long since I remember being so moved by the profound pain of words and music. It is the expression of his own heart’s anguish. If only he could speak so candidly in his own words!”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Johannes Brahms: Alto Rhapsody, Op. 53