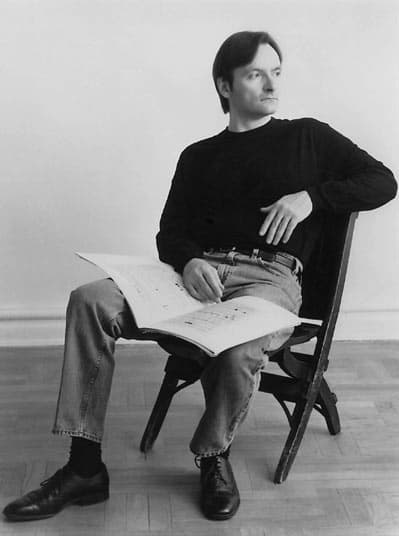

Stephen Hough has been described as “one of the most distinctive artists of his generation.” And while his achievements as a pianist are well-known and documented, Hough is also a published and frequently commissioned composer. But what is more, he is a respected writer with three books and hundreds of articles to his name, and a solo exhibition of his paintings was presented in London in 2012. It’s hardly surprising that The Economist included him in the list of “Twenty Living Polymaths.”

Stephen Hough

Hough was born on 22 November in Heswall on the Wirral Peninsula, and grew up in Thelwall, just south of Manchester. His father, born in Australia, worked as a technical representative for British Steel, and his aunt Ethel owned a piano. For Hough, it was love at first sight and he begged his parents to let him take piano lessons. He started lessons with Miss Riley at the age of five, but since his mother had a friend with connections to the Royal Northern College of Music, Heather Slade-Lipkin took over. Hough recalls, “to Heather I owe a tremendous amount of my early pianist and musical education. She gave me a solid and thorough grounding without which it is impossible to build later.”

Stephen Hough Plays Liszt

Slade-Lipkin apparently insisted that Hough begins with lots of technical exercises. “We did Beringer, Pischna, and Joseffy exercises,” recalls Hough, “and I remember her watching my hands like a hawk to make sure that my fingers were not collapsing at the joint.” Hough made rapid progress and received a special mention from a judge in the North-West junior piano competition at the age of eight. The press quickly dubbed him the “new Mozart,” but not everything was smooth sailing.

Hough had a terrible, recurring fear of being mugged, and when it actually did happen at the age of 12, things dramatically changed. “From being a relatively happy child, he became an introverted young teenager whose talent was obscured for a while from everyone including himself.” Hough remembers, “I had a patchy year when a lot of time was spent at home watching six hours a day of television. I went into myself. Looking back it wasn’t so dramatic: two or three boys punching me in the stomach demanding money. It was just that the big fear had finally actually happened.” He studied at Chetham’s School of Music, which he later described as “not a wonderful place while I was there,” and subsequently at the Royal Northern College.

Stephen Hough Plays Chopin’s Nocturne Op. 9, No. 2

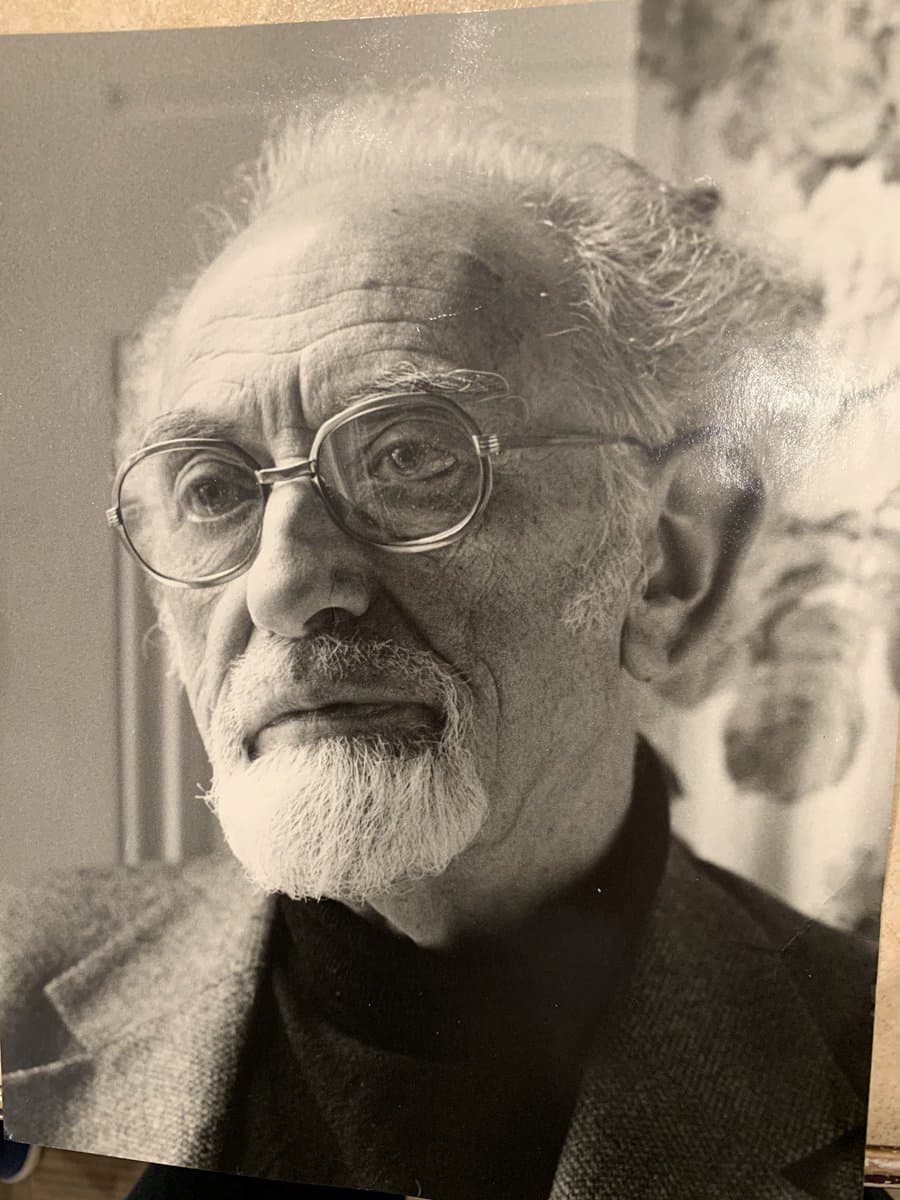

From the age of ten, Hough studied with Gordon Green for a total of eight years, and he describes it as “one of the most marvelous influences in my life.” Green was intent on developing a certain kind of maturity and self-awareness, “as he trusted you enough to allow you to work out your feelings about a piece over a period of time, even if what you were doing then was not always in the best taste, or at least it could be improved upon.”

Gordon Green

For Hough it was a “combination of trust and humility which looked at the long term and ignored the allure of winning prizes and competitions at an early age.” Hough greatly appreciated the artistic aura that Green was looking to create. “His studio had an ambiance of culture, of sensitivity, of talent. He would, for example, mention literature if it were relevant to a discussion, for there were always innumerable books around his studio.” Apparently, Green placed less emphasis on technique, which Hough considered a definite drawback. “I grew more and more dissatisfied with any playing from a technical point of view, and it wasn’t really until studying with Derrick Wyndham, who was a child prodigy and student of Rosenthal and Schnabel, that certain knots in my equipment began to be unraveled.”

Johann Nepomuk Hummel: Piano Concerto No. 2 in A Minor, Op. 85 (Stephen Hough, piano; English Chamber Orchestra; Bryden Thomson, cond.)

Hough recalls, “that Wyndham was a very different teacher and personality in many ways, but every bit as wonderful and invaluable to me… He chided me for my errors and for my attitude, which he said was dangerous if taken too far. He had a very analytical mind, and I learned to analyze where the problems arose.” Hough related that he found it useful to practice with his eyes closed and that the biggest problem in playing is to listen objectively to oneself. Hough freely admits that he “suffers from any and all kinds of chronic nerves, certainly not like some who are really paralyzed and unable to give their best… But if we only care about the music, we won’t think of being nervous, but if we care what people think of us, then we will be.”

Hough was a finalist in the BBC Young Musician of the Year Competition and won the piano section. And in 1983, he took first prize at the venerable Walter Naumburg International Piano Competition, which takes place in New York City every three years. He remembers, “One minute I was thinking that the first rounds of a piano competition at the Juilliard were a long shot and not bothering to practice; the next minute I was in the final at Carnegie Hall, and then I won!” Winning that competition was the starting point of a truly international career, but it was not necessarily easy. “At 21 I suddenly had to be grown up: I had a manager and concerts, and frankly I wasn’t prepared.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Stephen Hough Plays Rachmaninoff’s Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, Op. 43