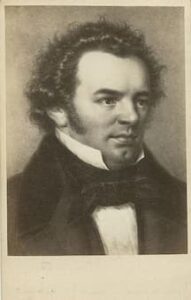

Franz Schubert

On 19 November 1828, Franz Schubert died at the age of 31 in his brother’s flat in Vienna. He had been seriously ill for some time, with the primary symptoms of syphilis presenting themselves as early as December 1822. Premonitions of death consistently haunted Schubert following his diagnosis, and he wrote to a close friend, “I feel myself to be the most unhappy and wretched creature in the world. Imagine a man whose health will never be right again, a man whose most brilliant hopes have perished, to whom love and friendship have nothing to offer but pain, whose enthusiasm for all things beautiful is gone, and I ask you, is he not a miserable, unhappy being? Each night, on retiring to bed, I hope I may not wake again, and each morning but recalls yesterday’s grief.” His physical and mental health oscillated between hope and despair, and Schubert took to bed with a fever on 5 November. Suffering from tertiary syphilis and the effects of highly toxic mercury treatment, Schubert passed away at 3pm on 19 November. His final and horribly painful days in November 1828 included bouts of delirium, ceaseless singing, and moments of great lucidity when he was working on his compositions. Astonishingly, with the period between the spring and autumn of 1828, Schubert composed his last major compositions for solo piano, the sonatas D 958, 959 and 960.

Franz Schubert: Piano Sonata in C minor, D. 958

Portrait of Schubert by 3D Sculptor Hadi Karimi

Schubert’s three last sonatas are “cyclically interconnected by diverse structural, harmonic and melodic elements tying together all movements in each sonata, as well as the three sonatas, respectively; consequently, they are often regarded as a trilogy. By including specific allusions to his earlier compositions, Schubert appears to have crafted three highly personal and autobiographical works. Scholars and researchers have even suggested that the sonatas follow specific psychological narratives. In musical and structural terms, all three sonatas share a common dramatic arc, “making considerable use of cyclic motives and tonal relationships, and weave specific musical ideas into the developing narrative.” Each sonata unfolds in four movements, with the exposition of the opening movements exploring two or three thematic and tonal areas. Themes are irregularly constructed and digress into far-flung harmonic regions. Development sections violently plunge the listener into new tonal areas, and a new theme based “on a melodic fragment is presented over recurrent rhythmic figuration, and then developed, undergoing successive transformations.” The opening movements of all three sonatas resolve all internal conflicts and conclude in quiet peacefulness.”

Franz Schubert: Piano Sonata in A Major, D. 959 (Mitsuko Uchida, piano)

Schubert at the Piano – Gustav Klimt (1899)

The slow movements of all three sonatas are cast in tonally remote keys, and feature two contrasting sections in key and character. In his third movements, Schubert references dances, including “playful figurations for the right hand and abrupt changes in register.” The themes of Schubert’s Finale movements are characterized by “long passages of melody accompanied by relentless flowing rhythms.” Structural and musical similarities aside, the last Schubert sonatas illustrate powerfully emotional states with the music weaving in and out of dreams and memories. Given the proximity of these sonatas to Schubert’s death, they have been read against a background of a psychological or biographical narrative.

Schubert’s death mask

It has been suggested that the sonatas “portray a protagonist going through successive stages of alienation, banishment, exile, and eventual homecoming, or self-assertion. Discrete tonalities or tonal strata, appearing in complete musical segregation from one another at the beginning of each sonata, suggest contrasting psychological states, such as reality and dream, home and exile, etc.; these conflicts are further deepened in the ensuing slow movements. Once these contrasts are resolved at the finale by intensive musical integration and the gradual transition from one tonality to the next, a sense of reconciliation, of acceptance and homecoming, is invoked.” It is entirely plausible that the sonatas do convey Schubert’s feelings of loneliness and alienation, and that the process of composition became a kind of psychological therapy. And if you are looking for a depressing postscript, the sonatas D 958, 959 and 960 were not even published until ten years after Schubert’s death, and they were greatly neglected in the 19th century.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Franz Schubert: Piano Sonata in B-flat Major, D. 960

I didn’t know anything about his health. Why he was ill doesn’t matter to me: it’s the fact that through this agony he was able to compose such beautiful music. I wonder if he even realized that his music down through the years would bring peace and happiness to the world.