In popular perception, the Russian composer Nikolai Andreyevich Rimsky-Korsakov (1844-1908) is primarily associated with the ideas of the “Mighty Handful.” This group of five prominent Russian composers attempted to create a distinct musical style that sought to capture elements of rural Russian life, to build national pride, and to prevent Western ideas from seeping into their culture.

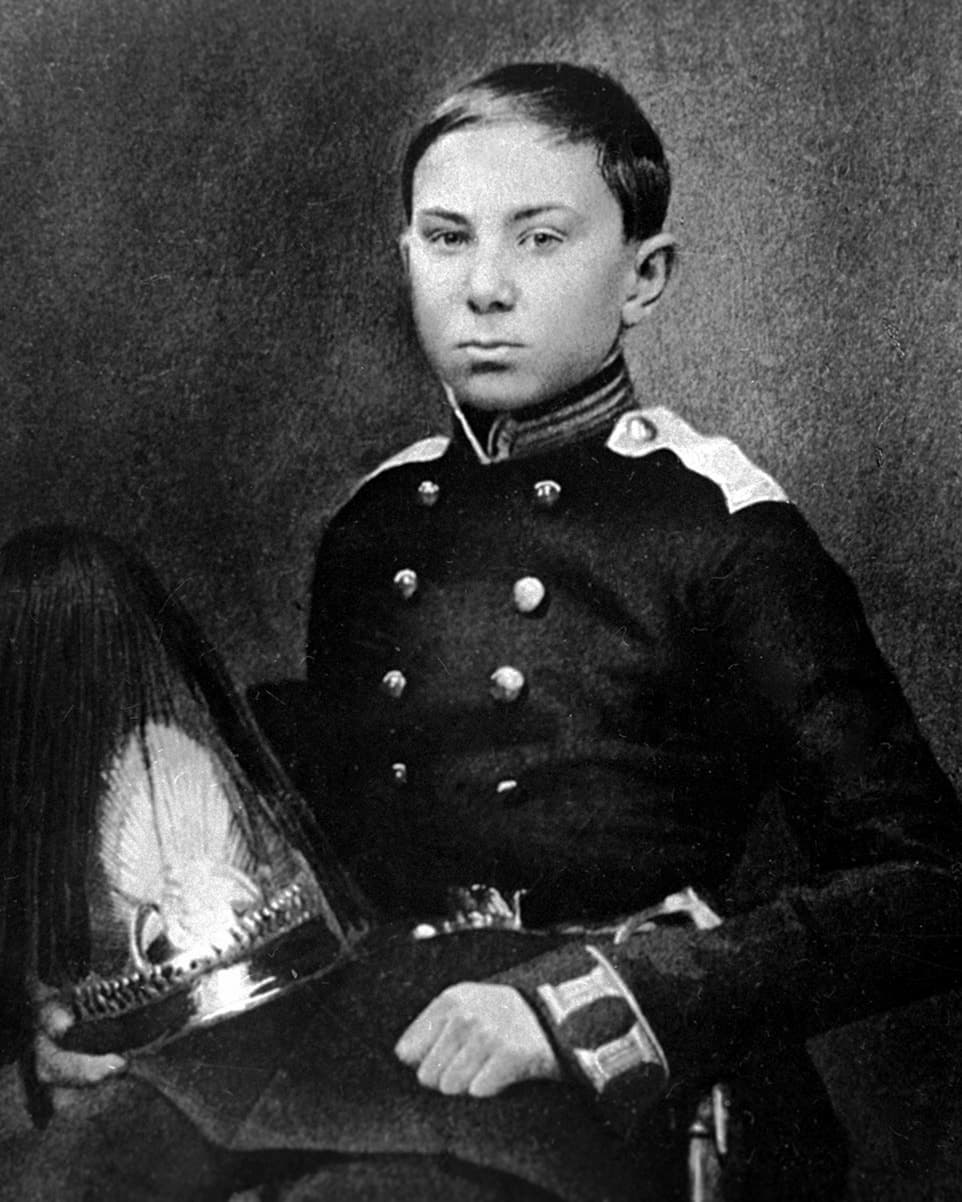

Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov as a cadet

While Rimsky-Korsakov started out as a dedicated member of the group, his style changed once he had mastered textbook harmony, and he turned away from their radical experiments. He became openly sceptical about musical nationality at home, but was celebrated outside his homeland precisely for his exotic Russianness.

Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov: Russian Easter Overture, Op. 36

Ancestry

Rimsky-Korsakov was born on 18 March 1844 in Tikhvin, a town roughly 200 kilometres east of Saint Petersburg. He was born into a noble family that traces back to Ivan Rimsky-Korsakov, famously a lover of Catherine the Great. Subsequently, Lieutenant-General Peter Voinovich Rimsky-Korsakov apparently abducted the daughter of an Orthodox priest, and the couple had six children, including Nikolai’s father Andrei Petrovic Rimsky-Korsakov.

Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov’s parents

Andrei served in the Interior Ministry of the Russian Empire, and he was a leading Freemason. He was a simple and kind-hearted man, who voluntarily freed his serfs. His first wife, Ekaterina Meshcherskaya had died just nine months after their marriage, and his eye now fell on Sofya Vasilievna. She was the illegitimate daughter of a peasant serf and a wealthy landlord. Since her father vehemently disagreed on a possible union, Andrei abducted his bride and brought her to Saint Petersburg, where they married.

Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov: Fantasia on Two Russian Themes, Op. 33 (Aaron Rosand, violin; Luxembourg Radio Orchestra; Louis de Froment, cond.)

Musical Aptitude

Sofya Vasilievna Rimsky-Kosakov was an intelligent and devout woman with a great deal of musical talent. Nikolai would later notate a number of folksongs he had heard her singing during his childhood. In the event Sofya Vasilievna was eighteen years younger than Andrei, and Nikolai’s older brother Voin would become a well-known navigator and explorer. Voin was 22 years older than Nikolai, and would become a powerful influence.

Voin Rimsky-Korsakov

As Nikolai tells us in his memoires, “The first sign of musical ability showed themselves in me very early. Before I was two I could distinguish all the melodies my mother sang to me; at three or four I was an expert at beating time on a drum to my father’s piano playing… I soon began to sing very accurately everything he played, and often sang with him; then I began to pick out the pieces with harmonies for myself on the piano.”

Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov: “Flight of the Bumblebee”

First Lessons

Around the age of six Nikolai started taking piano lessons from a neighbourhood teacher, but he wasn’t really all that interested. As he remembered, “I played inaccurately and was weak at counting.” In fact the young boy was powerfully drawn to literature and he later recalled that “from his reading, and tales of his brother’s exploits, he developed a poetic love for the sea without ever having seen it.” He started composing at the age of ten, but two years later he was encouraged by his brother Voin to join the Imperial Russian Navy.

In 1856 Nikolai entered the School for Mathematical and Navigational Sciences in Saint Petersburg. Carefully monitored by his brother, the teenager started to develop a taste for opera. Productions of Donizetti’s Lucia, Glinka’s A Life for the Tsar and Meyerbeer’s Robert le diable encouraged a growing interest in music. As he wrote to his parents back home. “Whereas the genuine piano music is so dry and boring, when you play an opera, you imagine you’re sitting in the theatre, listening or even playing or singing yourself.”

Nicolai Rimsky-Korsakov: Piano Quintet in B-flat Major (Eva Knardahl, piano; Gothenburg Wind Quintet)

The Lure of Music

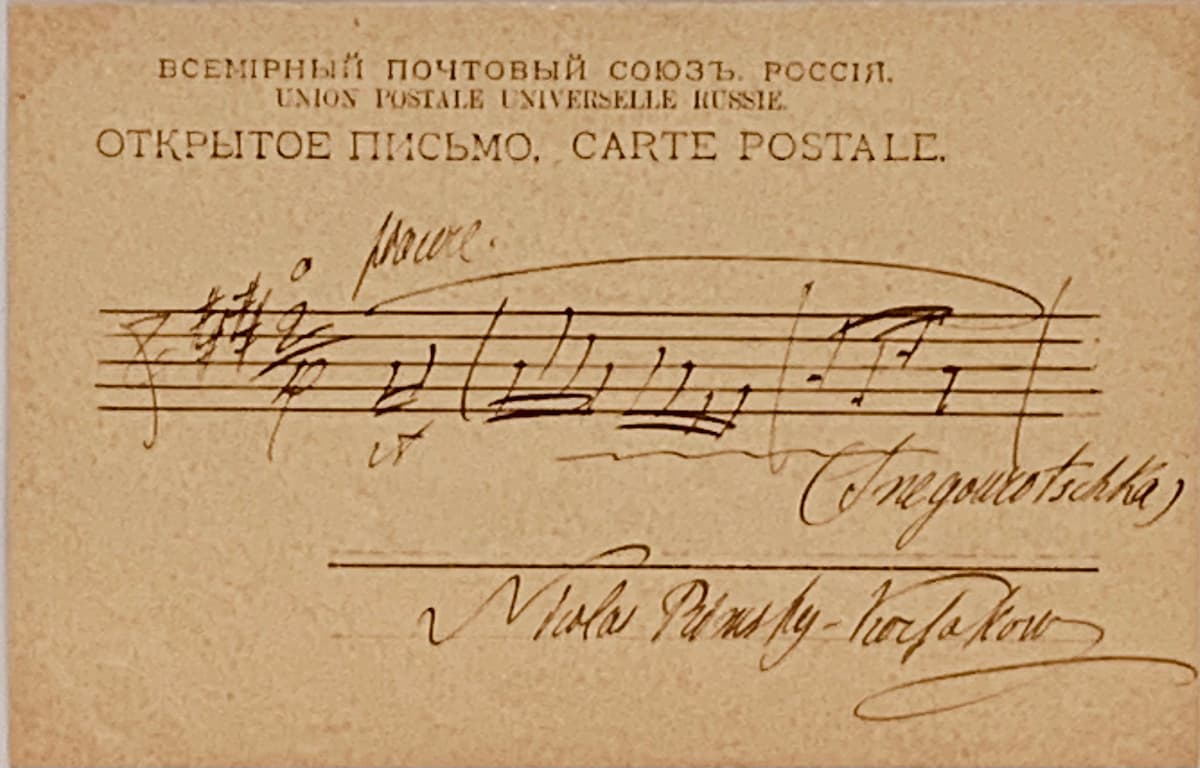

Rimsky-Korsakov’s autograph

Initially, his brother Voin had been supportive of his brother’s musical activities, and even hired a room with a piano for him. And a new teacher, Fyodor Kanille, introduced him to Bach, Beethoven and Schumann, and the “greatest musical genius Glinka.” Nikolai bought a score for Ruslan, “and I only half understood it, but the Italian names of the instruments, the different terms and clefs and the transpositions of the horns exercised on me a certain mysterious charm.”

Around the time Nikolai turned 17, Voin decided that music was taking away too much time from his brother’s studies, and he abruptly stopped his piano lessons. Nikolai was bitterly disappointed, but he had no choice. Concordantly, Kanille was reluctant to lose such an eager student, and he decided to give him lessons in theory and composition instead. Nikolai later wrote, “with what delight I listened to discussions on instrumentation, part writing and current musical matters. All at once I had been plunged into a new world, unknown to me.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter