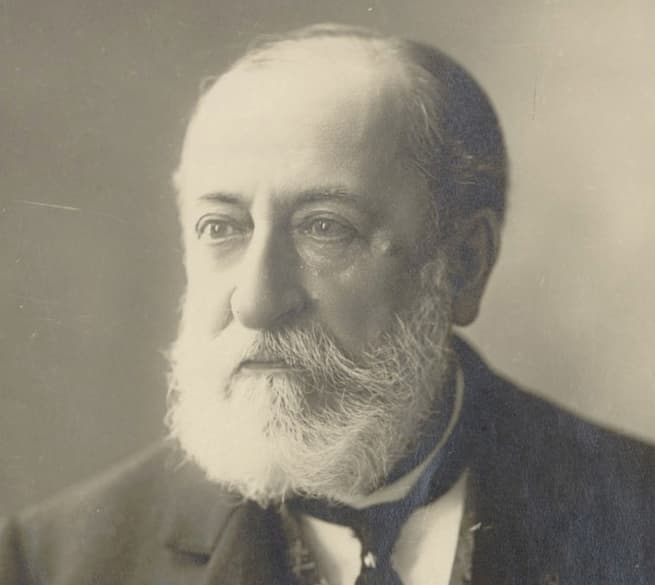

When Camille Saint-Saëns died of a heart attack on 16 December 1921 in Algiers, his body was taken back to Paris for a state funeral at the Madeleine. His career had spanned 70 years and five continents. He performed as a virtuoso, composed in nearly every musical genre, and wrote nearly as much prose as he did music. He networked with astronomers, philosophers, and botanists, and for a good many music lovers, he was the quintessential French musician.

Camille Saint-Saëns: Album pour piano, Op. 72

Saint-Saëns’ Eclectic Spirit

Camille Saint-Saëns © Gallica-BnF

Saint-Saëns was simultaneously open and resistant to new trends in music as he lived long enough to intersect with several generations. He was a scholar of music history and tolerant of a wide range of musical issues and directions. As he tellingly wrote, I am an eclectic spirit. It may be a great defect, but I cannot change it; one cannot make over one’s personality.”

During the final decades of his life, Saint-Saëns did become deeply concerned about musical decadence, his term for impressionism, and what he uncharitably called musical anarchy, his pet term for atonality. He was thoroughly convinced that human history repeats in a series of vast cycles and that “only works in which beauty unites with simplicity rise to the top.”

Camille Saint-Saëns: Suite in F Major, Op. 90 (Geoffrey Burleson, piano)

Musical Moderation

Tomb of Camille Saint-Saëns at the Montparnasse Cemetery

His steadfast dedication to musical moderation, clarity, balance, and precision earned Saint-Saëns the nickname “French Beethoven,” yet he was simultaneously called the “greatest composer without talent.” For a variety of extra-musical reasons, he was never taken seriously as one of the great French composers of the late 19th century. As he wrote in his memoirs, “Music is something besides a source of sensuous pleasure and keen emotion, and this resource, precious as it is, is only a chance corner in the wide realm of musical art.”

There were plenty of attempts to push Saint-Saëns music to the sidelines of history, but he had no intention of letting his critics off lightly. “He who does not get absolute pleasure from a simple series of well-constructed chords,” he writes, “beautiful only in their arrangement, is not really fond of music.” And while he strongly defended Liszt, Bizet, and Wagner, he was clearly allergic to any kind of Wagnerism.

Camille Saint-Saëns: Thème Varié, op.97

Political Convictions

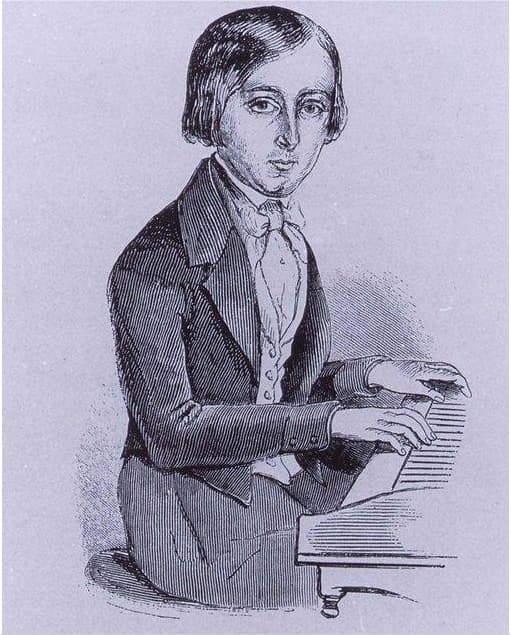

Camille Saint-Saëns in 1846

Saint-Saëns placed his convictions into the service of the Société Nationale de Musique by promoting a new, serious style of composition and a young generation of French composers. On the heels of France’s defeat in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71, Saint-Saëns was determined to “spread the gospel of French music and make known the works of living French composers.”

As Jann Pasler writes, “Saint-Saëns vigorously supported democratic republican ideals in his music.” His left-of-center attitude when the Republicans came to power in 1879 shifted towards the center when Republicans made alliances with conservative monarchists to fight anarchism and the spread of socialism in the 1890s.

Camille Saint-Saëns: Allegro appassionato, op. 70

Orientalism in Saint-Saëns’ Music

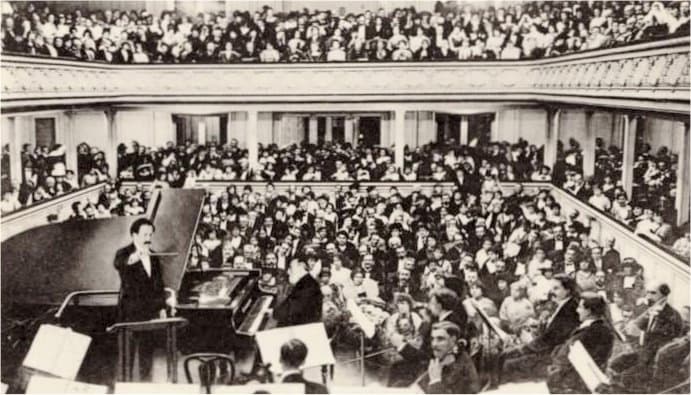

Saint-Saëns farewell concert in 1913

In order to avoid falling back into civil war, the government needed a sense of history that “incorporated the heritage of both the ancient regime and the Revolution, and Saint-Saëns sought musical ways to negotiate tradition and modernity. For Saint-Saëns, the future held a world of assimilation and the acceptance of the republican ideals at home and also abroad among the colonies.

His Orientalism explored pentatonic scales and the augmented seconds of Arabic music, creating musical heterogeneity and coexistence. Saint-Saëns was keenly interested in the newest and emerging technologies, recording his music on the gramophone and even writing music for an early film. His music has never been far from the concert hall, and its craftsmanship, beauty, and luminous clarity continue to appeal to performers and audiences in the 21st century.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter