Claude Debussy

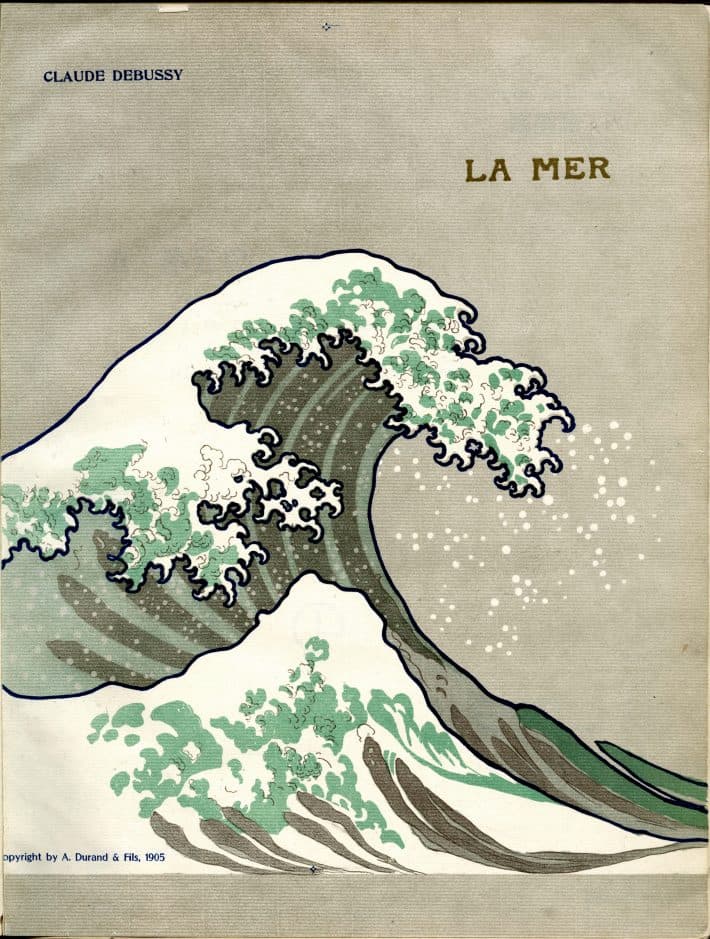

Claude Debussy writes, “I love music passionately. And because I love it, I try to free it from barren traditions that stifle it. It is a free art gushing forth, an open-air art boundless as the elements, the wind, the sky, the sea.” Given Debussy’s love for music and the sea, it comes as no surprise that he combined both elements in one of the supreme achievements in symphonic literature. La Mer, one of his most concentrated and brilliant works in the repertoire, was composed between 1903 and 1905 and premiered on 15 October 1905, at the Concerts Lamoureux in Paris under conductor Camille Cheviallard. La Mer is dedicated to Debussy’s publisher Jacques Durand. Debussy had finished the work in March 1905 at the Grand Hotel at Eastbourne on the coast of the English Channel, a location he described as “a charming peaceful spot. The sea unfurls itself with utterly British correctness.” The cover illustration of the first edition, however, is anything but calm as it pictures a detail from the famous woodblock print “The Great Wave off Kanagawa” by Japanese artist Katsushika Hokusai. It was one image out of a series of “Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji,” depicting the area around Japan’s near-sacred mountain under specific atmospheric and seasonal conditions. In his published detail, Durand forgoes the stately image of Mount Fuji but focuses instead on the “great wave,” creating an image that communicated the sense and expectation of the impending breaking of the wave.

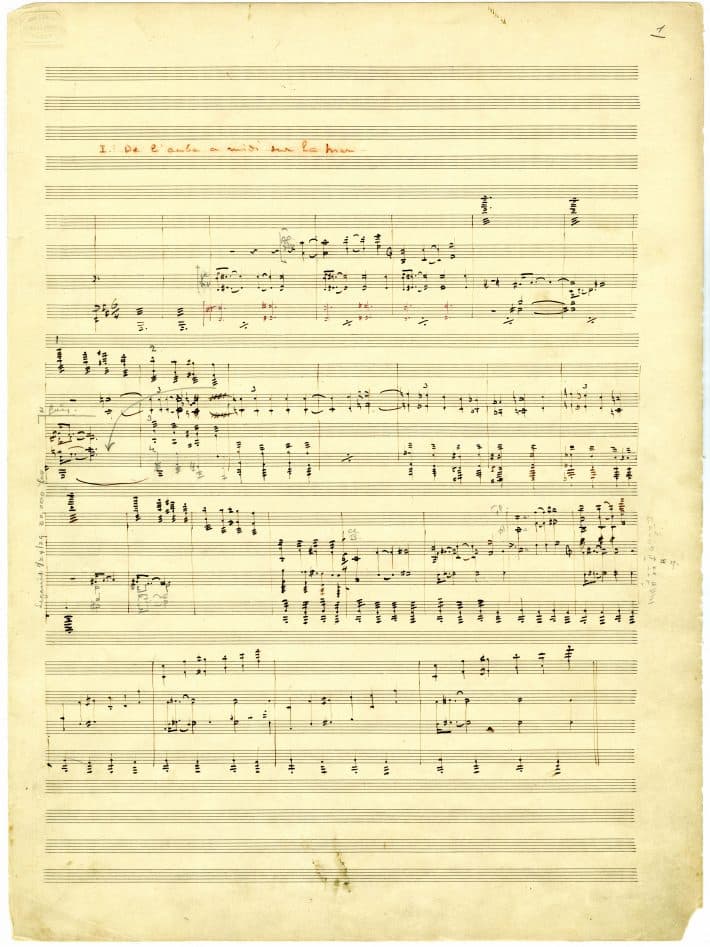

Claude Debussy: La Mer, “De l’aube à midi sur la mer”

Cover image of La Mer featuring the famous “The Great Wave off Kanagawa” by Hokusai

At one point in his life, Debussy had actually thought of becoming a sailor, and he kept a lifelong attachment to “my old friend, the sea; it is always endless and beautiful. It is really the thing in nature which best puts you in your place.” Debussy referred to La Mer as “trois esquisses symphoniques,” as “three symphonic sketches.” However, it is clearly not a symphony as it deliberately rejects traditional symphonic form. For Pierre Boulez, La Mer does “best fulfill the conditions of the genre in the most usual sense of the term, especially if one considers the effective coda of the last movement which carries to its maximum the rhetoric of the culminating point, a rhetoric practically lacking in all his other orchestral pieces.” A good many close friends of the composer seemed to have been disappointed after listening to the work at the premier. A critic writes, “the rich wealth of sounds that interprets this vision of the sea with such accuracy and intensity, flows on without any unexpected jolts, its brilliance is less restrained, its scintillations are less mysterious. It is certainly genuine Debussy—that is to say, the most precious and most subtle expression of our art—but it almost suggests the possibility that someday we may have an Americanized Debussy.”

Claude Debussy: La Mer, “Jeux de vagues”

Manuscript of La Mer page 1 of the first movement “De l’aube à midi sur la mer”

Debussy clearly wanted to break free of formal conventions. As he famously wrote, “I am more and more convinced that music is not, in essence, a thing which can be cast into a traditional and fixed form. It is made up of color and rhythm.” And it was Debussy’s use of color as an end in itself that counts as among the most influential legacies of his work. Augmenting the standard orchestra with two harps and a large percussion section might simply be considered surface ornamentation. However, Debussy uses other musical elements in his quest for orchestral color. “Harmonic changes serve as color washes; chords dissolve rather than resolve. Short melodic motives rather than fully developed themes sparkle in brief solos, substituting timbre and movement for narrative coherence.” And let’s not forget the interaction of timbre, the use of non-Western scales, and incessant cross-rhythms that portray the unsettled nature of the waves.

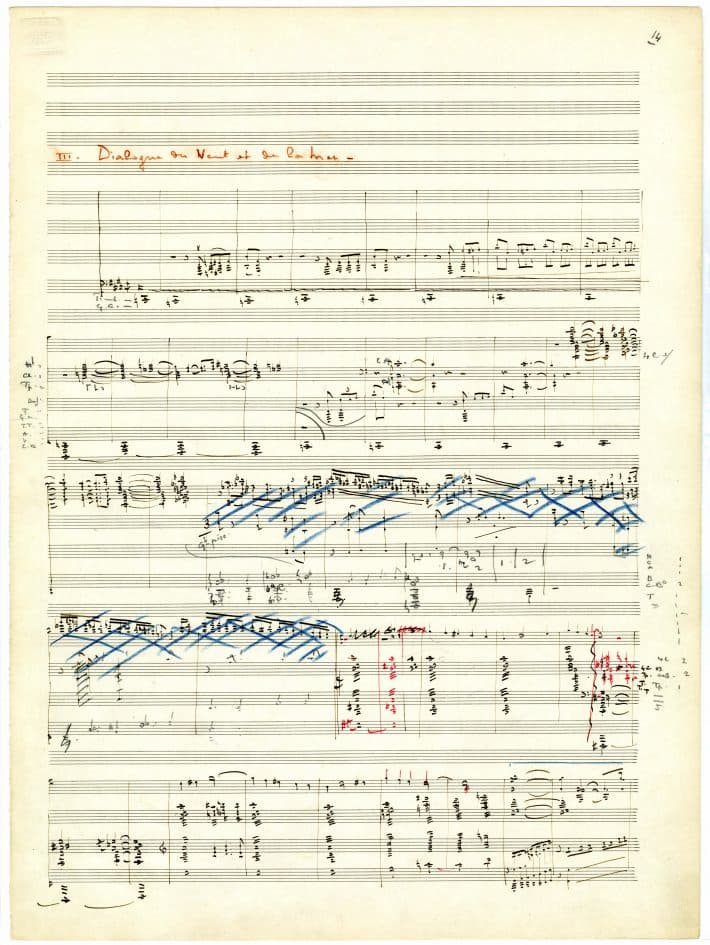

Claude Debussy: La Mer, “Dialogue du vent et de la mer”

Manuscript of La Mer third movement “Dialogue du vent et de la mer”

Debussy made several transcriptions of his orchestral works for piano four-hands, including La Mer. In essence, he responded to requests from his publishers for whom this was the best means of introducing his symphonic works to a wider public. This particular task for transcribing orchestral works for piano was generally carried out by musicians under contract to the publishers. In the case of Durand, many transcriptions for piano four-hands were fashioned by Albert Benfeld, better known under the pseudonym Albert Kopff. Kopff had taken on the Debussy “Quartour,” and the composer was highly irritated with what he considered a myriad of mistakes. Debussy writes, “It is a little facile to move the parts up one floor just for convenience, as I would have much preferred to have equivalence of sound.” As such, Debussy himself carried out the transcription for La Mer, which he completed in September 1905. As a scholar wrote, “this version more clearly reveals the structure by abandoning the admirable shimmering orchestral colors in favor of a vision in black and white.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Claude Debussy: La Mer (version for piano 4 hands) (Joseph Tong, piano; Waka Hasegawa, piano)