In 1917, Igor Stravinsky and Pablo Picasso made an excursion to Naples, with the composer commenting on its “half Spanish character, on the pleasure he found in the aquarium, and in the Neapolitan watercolors.”

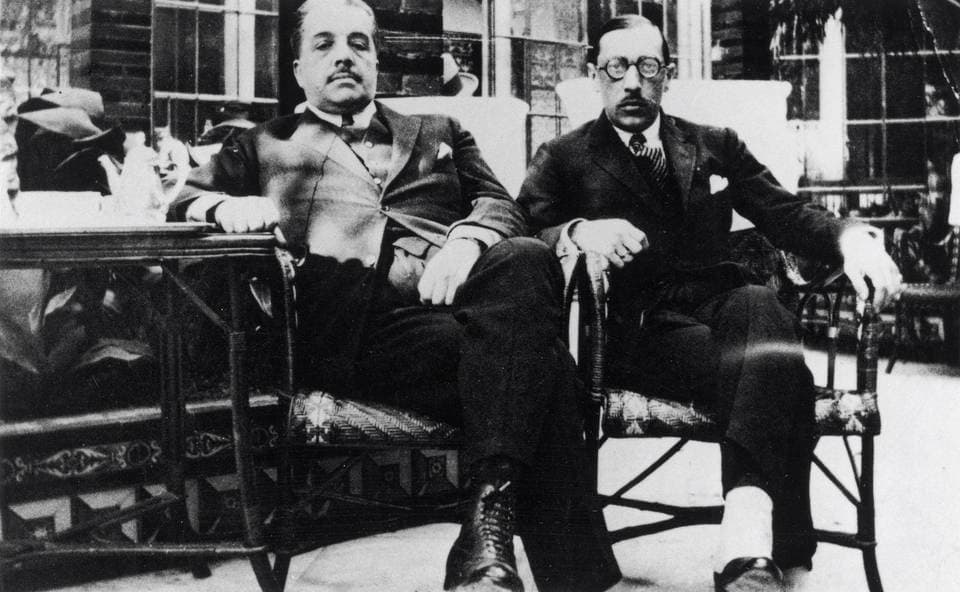

Serge Diaghilev and Igor Stravinsky, 1921

They also attended a commedia dell’arte performance, a genre originating in 15th-century Italy. This form of theatre incorporated specific roles and characters represented by a singular costume and dedicated mask. Improvising on themes of adultery, jealously and elderly gentlemen seeking the affections of younger women, this type of entertainment quickly flourished throughout Europe. Characters included the predecessor of the modern clown (Arlecchino), the military gentleman (Il Capitano) and a character with an extremely long nose resembling a peak, known as “Pulcinella” or “Punch.” With the end of World War I, the Russian impresario Serge Diaghilev had reconstituted his “Ballets Russes” for performances in London, and in 1919 he designed a ballet scenario based on the “Pulcinella” character.

Igor Stravinsky: Pulcinella, “Overture” (Seattle Symphony Orchestra; Gerard Schwarz, cond.)

Igor Stravinsky: Pulcinella, “Serenata” (Gran Wilson, tenor; Seattle Symphony Orchestra; Gerard Schwarz, cond.)

Pablo Picasso, 1912

Looking back at a number of highly successful collaborations, Diaghilev approached Stravinsky to provide the music. However, Stravinsky was initially not enthusiastic, as Diaghilev wanted the music to be based on compositions he found in the Naples Conservatory attributed to the 18th-century Italian composer Giovanni Battista Pergolesi. Stravinsky eventually committed, and he quickly understood that he could not recompose Pergolesi, but “that he could only compose the act of possessing.” Stravinsky later explained that he “approached his model not with respect but with love.” As the composer reports, “I began by composing on the Pergolesi manuscripts themselves, as though I were correcting an old work of my own. I knew that I could not produce a forgery of Pergolesi because my motor habits are so different; at best, I could repeat him in my own accent.” A scholar writes, “The remarkable thing about Pulcinella is not how much but how little was added or changed.”

Igor Stravinsky: Pulcinella, “Allegretto” (Susan Graham, soprano; Gran Wilson, tenor; Jan Opalach, bass; Seattle Symphony Orchestra; Gerard Schwarz, cond.)

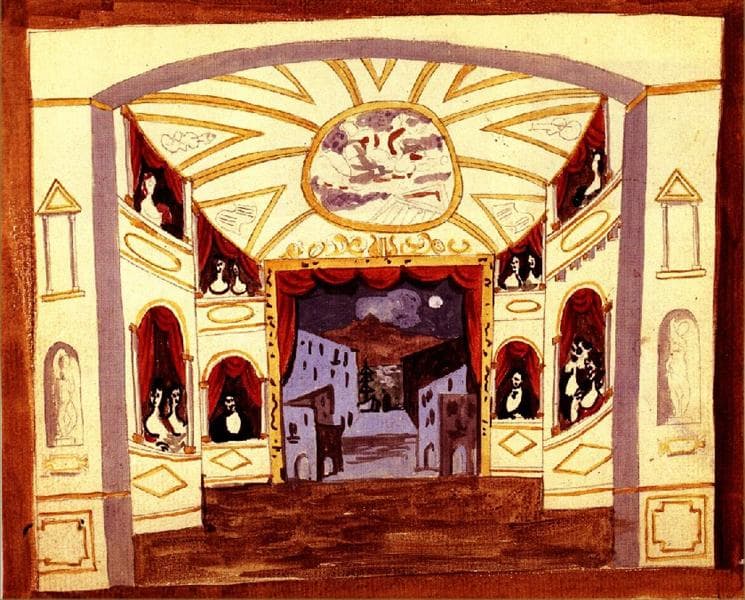

Picasso’s scene design for Pulcinella, 1920

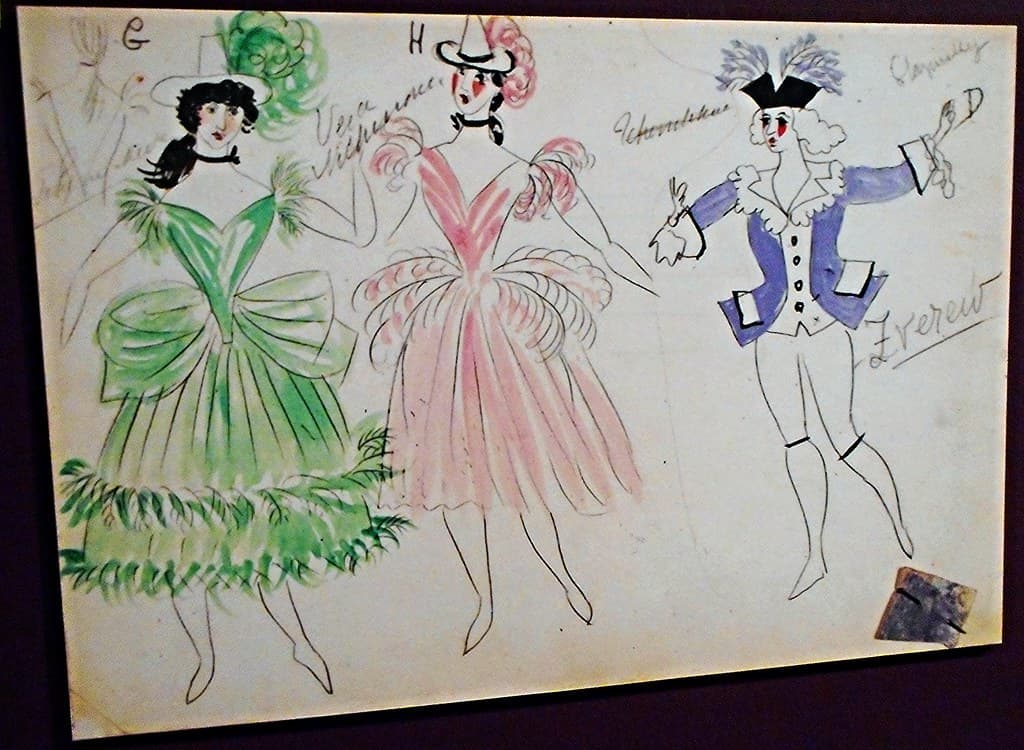

Stravinsky erased some chromatic passages, collapsed the upbeat into the first downbeat, broke up the regular phrasing, “and parceled the music out to wind ensembles, effectively constraining the rhythmic give that the original would seem to imply.” With stage and costume designs by Picasso, based on traditional Italian themes, and using 18th-century ballet steps, Pulcinella premiered at the Paris Opera on 15 May 1920. The ballet action is an adaptation of a commedia dell’arte piece, with the carnal trickster “Pulcinella” outwitting his companions and getting the girls. However, there is a clear disconnect between the masquerade on stage and the music. Stravinsky provides a shockingly colorful mask, as he uses bygone music, which definitely does not sound like originating in the eighteenth-century. As a scholar writes, “there is a very evident gap between mask and face, or perhaps better, between puppet and puppeteer.” For Stravinsky the Pulcinella project was a glance back into the 18th century. However, featuring a new and ingenious combination of instruments, Stravinsky did not simply emulate the old master. By elongating individual phrases and imparting a sense of driving rhythms unequivocally rooted in the 20th century, he manages to transport the music of the past into the present.

Igor Stravinsky: Pulcinella, “Trantella” (Seattle Symphony Orchestra; Gerard Schwarz, cond.)

Igor Stravinsky: Pulcinella, “Andantino” (Susan Graham, soprano; Seattle Symphony Orchestra; Gerard Schwarz, cond.)

Pulcinella’s sketch by Picasso

The majority of music for Pulcinella originates from trio sonatas, with keyboard pieces, orchestral movements and arias making up the rest. “The words of the arias are retained, but distributed differently, with the placing of the songs determined by the action.” For contemporary audiences, Pulcinella sounded like charming, witty, and disarmingly simple 18th-century music. Surprisingly, it was fashioned by the same composer who had shocked Paris just seven years earlier with the fierce modernism of The Rite of Spring. However, it was equally radial as Stravinsky is pointing to the music of the distant past as an inspiration for the music of the future. As such, Pulcinella “is usually credited as the first music of neoclassicism, and it signaled a clear shift in Stravinsky’s own thinking.”

As Stravinsky later explained, “Pulcinella was my discovery of the past, the epiphany through which the whole of my late work became possible. It was a backward glance, of course, the first of many love affairs in that direction, but it was also a look in the mirror.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Igor Stravinsky: Pulcinella, “Gavotte” (Seattle Symphony Orchestra; Gerard Schwarz, cond.)

Igor Stravinsky: Pulcinella, “Vivo” (Seattle Symphony Orchestra; Gerard Schwarz, cond.)

Igor Stravinsky: Pulcinella, “Finale” (Susan Graham, soprano; Gran Wilson, tenor; Jan Opalach, bass; Seattle Symphony Orchestra; Gerard Schwarz, cond.)