Hailed by Gramophone Magazine as “one of the finest among the astonishing gallery of young virtuoso cellists,” Johannes Moser won the Tchaikovsky Competition in 2002. He performs both on acoustic and electric cellos in his effort to expand the reach of the classical genre to all audiences. Moser is equally passionate in commissioning new works for his instrument, with 27 commissions and counting to his name.

Johannes Moser Performs Reid’s “Somewhere there is Something Else”

Illustrious Ancestry

Johannes Moser

Born on 14 June 1979 in Munich, Germany, Johannes Moser comes from an illustrious musical family. His Canadian mother is soprano Edith Wiens, who had a celebrated international vocal career and still teaches voice at Juilliard. His father Kai Moser was a cellist in the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra for many years, and his aunt was the world-famous soprano Edda Moser. His grandfather was the musicologist Hans Joachim Moser, the son of music professor Andreas Moser, himself a student and early biographer of the violinist Joseph Joachim.

Growing up, as he explained in an interview, “I heard all sorts of repertoire from the earliest age, coming at me in all different directions… For me, it was all music and sound, the sound of my childhood.” In this intensely musical environment, Moser “absorbed a whole range of musical fragrances without being conscious of it.”

Antonín Dvořák: Cello Concerto in B Minor, Op. 104, B. 191 (Johannes Moser, cello; Prague Philharmonia; Jakub Hrůša, cond.)

Violin vs Cello

Edda Moser

Johannes Moser started his personal musical experience by studying the violin for two years. “It was an absolute disaster,” he explained, “because I really was the world’s worst violinist!” The main reason for starting to play cello, according to Moser, “was to get away from the violin.” His father being a cellist, there obviously was a cello in the house, and “as soon as I sat down with it and felt the vibrations, I felt at home with it, it was a good feeling.”

Moser had barely turned 6 years of age, but he felt completely relaxed with the cello and fell in love with it immediately. Playing a half-sized cello he could not yet get a full sound, but he started to fall in love with practicing. In a way, it was one of his first life lessons, “if you feel physically comfortable with something, learning it is so much easier.” Moser still can’t think of anything better than practising every day.

Johannes Moser Performs Bach’s Cello Suite No. 3 in C Major, “Courante”

David Geringas

David Geringas

Johannes heard a lot of cello repertoire at home because “my father would be playing all the time.” And later, “practicing the cello was the best excuse to avoid doing my math homework! My parents were ok with that as long as I was practicing my cello.” At age 18, in 1997, Moser started his studies with the Lithuanian David Geringas. Geringas had been a student of Mstislav Rostropovich, and he won the gold medal at the Tchaikovsky Competition in 1970.

“I studied with him for 8 years,” Moser explained, “and I certainly learned much from his physical interaction with the instrument. I probably learned as much from what he was talking about as watching him play.” As Moser recalled, “Geringas used his full body in terms of sound production, and his playing did not come across as particularly analytical. Nonetheless, when he was teaching me the Beethoven or Mendelssohn sonatas or the Russian masterpieces, he knew something about every note.”

Bohuslav Martinů: Cello Concerto No. 1, H. 196 (Johannes Moser, cello; German Radio Saarbrücken-Kaiserslautern Philharmonic Orchestra; Christoph Poppen, cond.)

Tchaikovsky Competition 2002

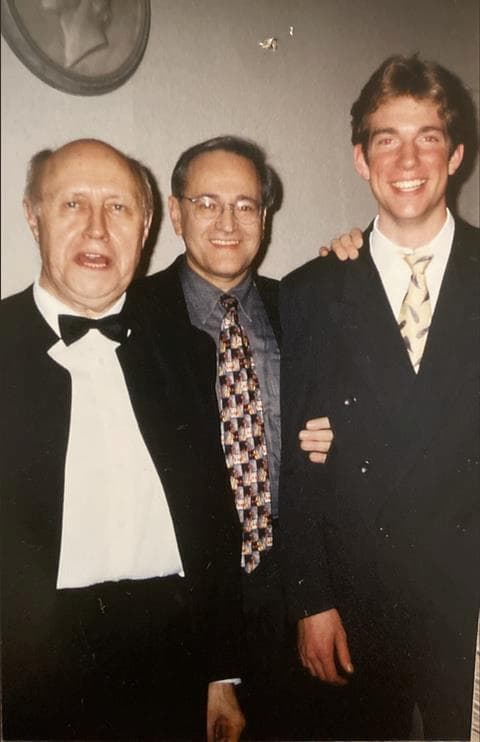

Johannes Moser with David Geringas and Mstislav Rostropovich

Moser was ready to follow in his father’s footsteps and applied for orchestral jobs. As he was about to undergo his diploma examination, Geringas recommended that he enter the Tchaikovsky Competition because the programme was very similar to what the diploma required. “So I thought: Ok, I will go to Russia and come home very early! Then I got lucky in the competition and got the 2nd Prize (no 1st Prize awarded). Suddenly, I had to rethink what I would do with my cello life.”

For Moser, it was truthfully “one of the hardest experiences of my life, as they didn’t really even feed us… I wish I could talk about inspiring moments but, in the end, I just wanted to go home.” Moser was somewhat surprised at how little impact and excitement his win at the Tchaikovsky actually generated. “I used to play some recitals and maybe a concerto once a year, and you would think things would change drastically, but nothing changed.” He did receive a couple of calls from conductors and did probably thirty conductor auditions. However, as he tells his students, “do competitions for the sake of advancing your knowledge about music and performance, but don’t think that the world will stop turning because you win a medal.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter