George Frideric Handel started work in his oratorio Jephtha on 21 January 1751. He was already well advanced in the score, setting the final chorus of Act 2, “How dark, O Lord, are thy decree,” when he was suddenly forced to stop. With his eyesight failing, he wrote in the score, in German, that the sight in his left eye had become “so relaxed” that he could not continue. Ten days later, he felt slightly better and resumed work, but on the 27th he had to stop work again.

George Frideric Handel: Jephtha, “How dark, O Lord, are thy decree”

Eye Surgeries

Handel with Messiah score

His affliction became widely known, and Sir Edward Turner noted that “Noble Handel hath lost an eye, but I have the Rapture to say that St Cecilia makes no complaint of any defect in his Fingers.” Handel did conduct Jephtha for the opening of the Lenten season, but it all ended prematurely because of the death of the Prince of Wales. With his vision now seriously impaired, Handel tried for a short “cure” at Cheltenham before returning to London to receive treatment from an eye surgeon.

In August 1752, a newspaper announced that Handel “had been seized with Paralytick Disorder in his Head, which has deprived him of Sight.” William Blomfield, the royal surgeon, attempted an operation, but any relief it produced was temporary. It was assumed that Handel had suffered a stroke, when in reality, he was suffering from cataracts, brought on by age and obesity. In the event the surgery only worsened the condition.

George Frideric Handel: Jephtha, “Ouverture”

The Will

John Taylor

Although blind and ill, Handel continued to supervise a number of oratorio seasons, but he was essentially unable to produce new compositions. He continued to consult various doctors and was operated on by the oculist and charlatan John Taylor. A poem seemingly celebrated the “recovery” of his sight, but it was probably not entirely truthful. Handel knew that things were coming to an end, and he drafted the first version of his will on 6 August 1756.

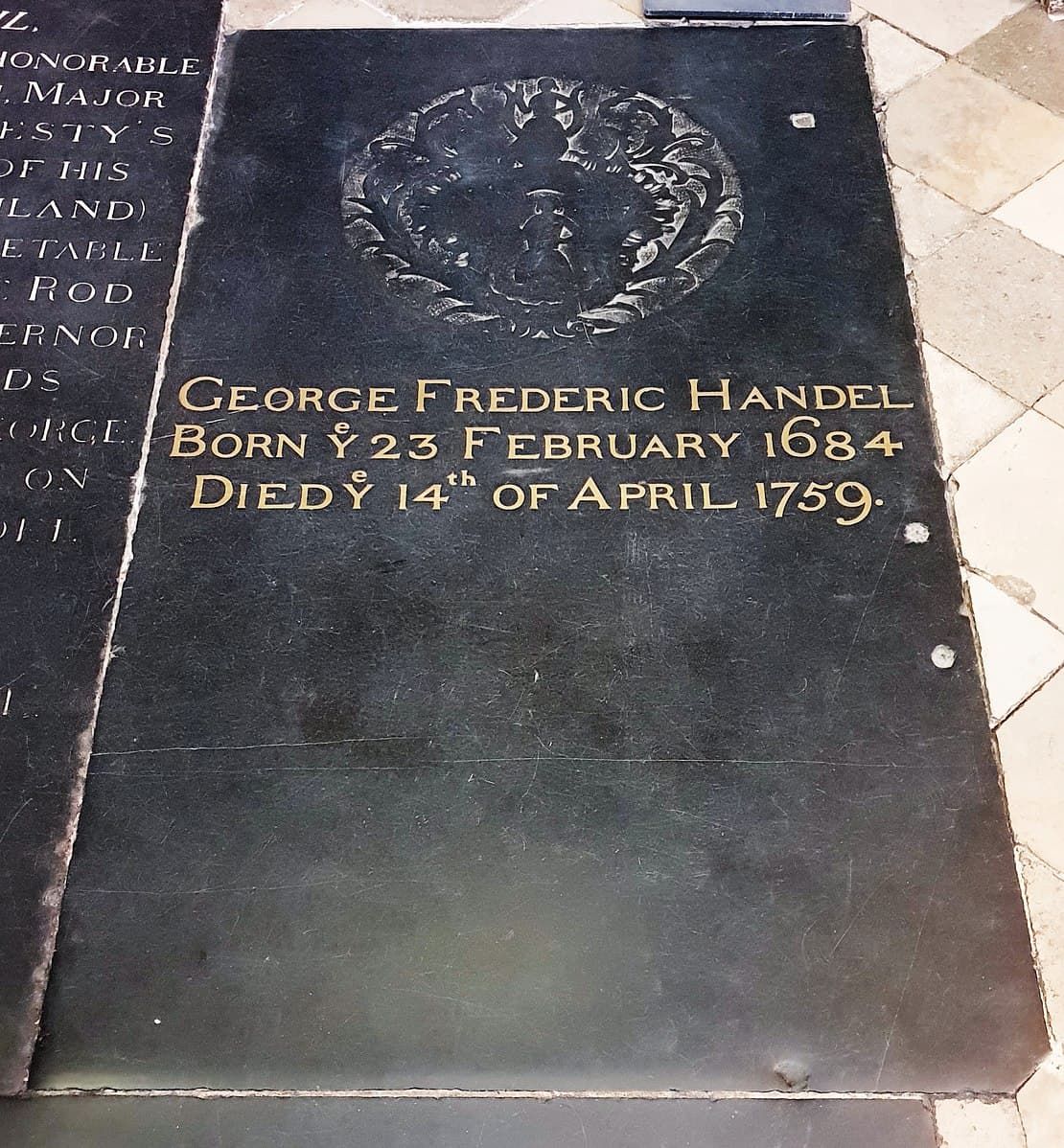

Handel took care of the shares made vacant by the death of several persons and increased the benefits to others. The composer kept adding various clauses and addendums over the years, with the final item, regarding the manner of his burial, dictated on 11 April 1759. As he bequeaths, “I hope I have the permission of the Dean and Chapter of Westminster to be buried in Westminster Abbey, in a private manner, at the discretion of my executor, Mr. Amyand, and I desire that my said executor may have to leave to erect a monument for me there and that any sum not exceeding six hundred pounds, be expended for that purpose, at the discretion of my said executor.”

George Frideric Handel: Jephtha, “Ye House of Gilead”

Death and Funeral

George Frideric Handel

Handel supervised his last oratorio during the 1759 Lenten season, and during a performance of Messiah, Handel suffered a fainting spell. He canceled a proposed trip to Bath and was confined to bed. As his friend James Smyth reported, “I had the pleasure to reconcile him to his old friends; he saw them and forgave them. He took leave of all his friends on Friday morning and desired to see nobody but his Doctor, Apothecary, and myself. He died on 14 April as he lived, a good Christian, with a true sense of his duty to God and man, and in perfect charity with all the world.”

The funeral took place on 20 April 1759, and his request for burial at the Abbey was granted. The London Evening Post reports, “The Bishop, Prebendaries, the whole Choirs attended to pay the last Honours due to his Memory; and it is computed there were no fewer than 3000 Persons present on this Occasion.” Handel’s wish for a private funeral service was clearly disregarded, and the monument on the wall above his grave was crafted by sculptor Louis Francois Roubiliac. The life-size statue, unveiled in 1762, shows the composer with the open score of “I know that my Redeemer liveth,” from Messiah.

George Frideric Handel: Messiah, “I know that my Redeemer liveth”

Legacy

Grave of Handel, Westminster Abbey

Handel became a national icon in Britain, “having with universal Applause, spent upwards of fifty Years in England.” While his Italian operas fell into obscurity, the oratorios continued to be, and still are, performed long after his death. And while his reputation primarily rests on his English oratorios, his secular cantatas have recently been revived.

These secular oratorios are closely related to his sacred works as they share the lyrical and dramatic qualities of his Italian operas. Based on classical mythology for subjects, “in the rediscovery of his theatrical works, Handel, in addition to his renown as instrumentalist, orchestral writer, and melodist, is now perceived as being one of opera’s great musical dramatists.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter