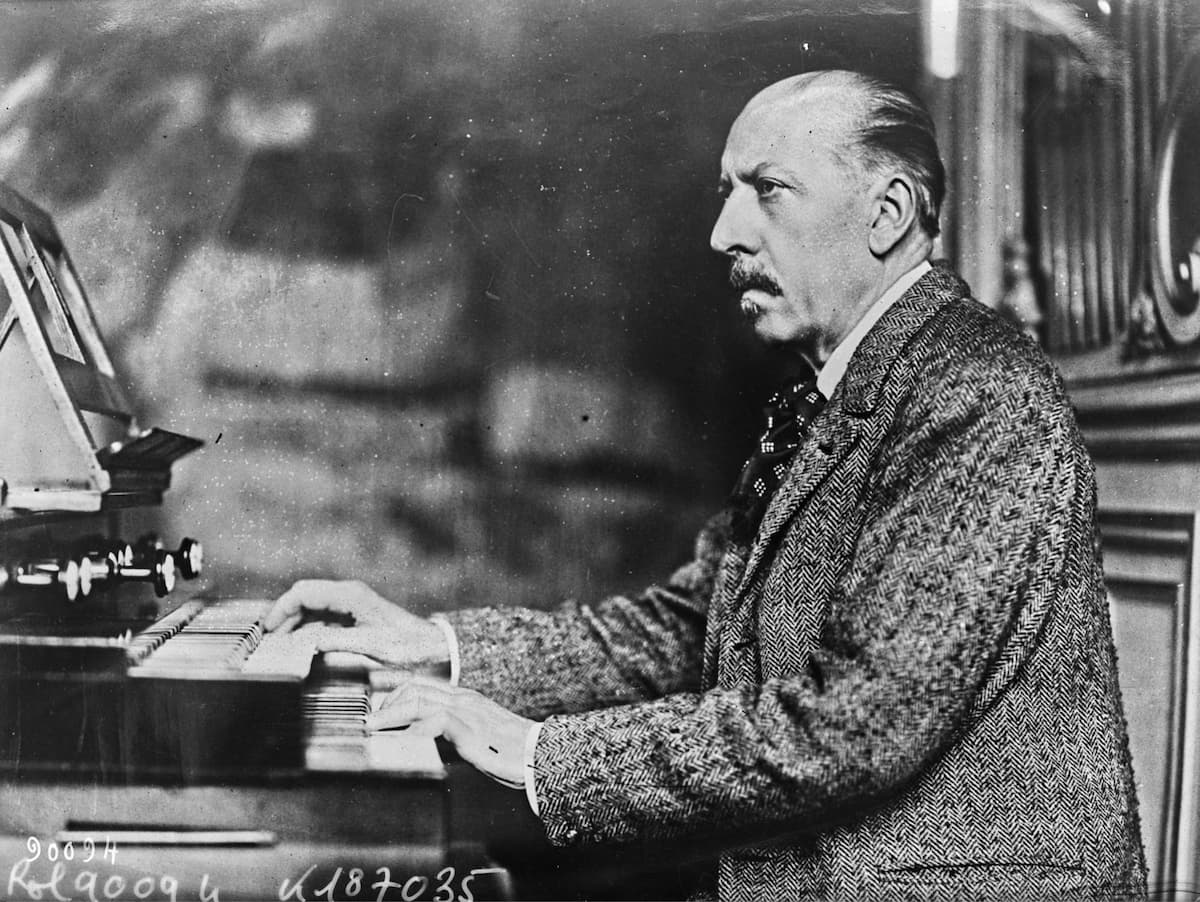

Charles-Marie Widor (1844-1937) left behind a substantial number of meticulously crafted compositions for various instrumental and vocal combinations. However, he is primarily remembered for his ten organ symphonies. Inspired by the magnificent Cavaillé-Coll organ at Saint-Sulpice in Paris, these works revolutionized the art of organ playing and composition in France.

Charles-Marie Widor: “Toccata,” Symphony No. 5

Final Instructions

By all accounts, Charles-Marie Widor was a man of captivating personality. Although he generally hid behind a façade of natural reserve, he was witty and warm-hearted. Highly energetic yet quietly spiritual, Widor was also a very humble man. He left specific instructions for preparing for his funeral. He declined a State Funeral, opting for a simple plainchant Requiem Mass at Saint-Sulpice.

Charles-Marie Widor

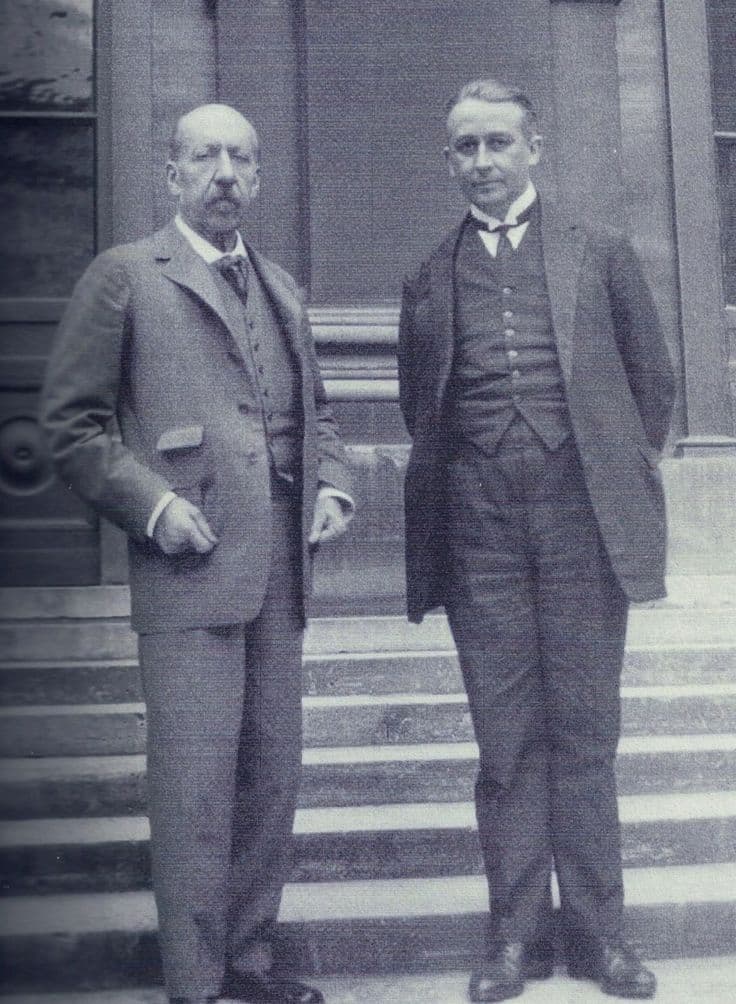

Widor died on Friday 12 March 1937, and according to his wishes, his coffin was taken to the church in evening darkness. Friends and relatives gathered in the nave while Marcel Dupré played music by Bach. Only on the following day did the French establishment turn out in force to pay their respects, and Isidor Philipp orated that “at the Institute, he had been an astonishingly animated force, and never had a Permanent Secretary been so greatly respected.” At the conclusion, Dupré played the Symphonie “Romane,” and the coffin was taken to its final resting place in the crypt behind a plain wooden grille.

Charles-Marie Widor: “Choral,” Symphony No. 7 (Romane)

Final Years

Widor remained mentally alert to his last day, and he produced a celebrated recording of his “Toccata” in 1932. As there had been some problems with placing the microphones and the church’s acoustics, the recording session lasted until midnight. A biographer writes, “showing no sign of fatigue, Widor took the recording engineer for a walk in the rain without an umbrella.” According to Widor, “the secret to long life is to work hard, eat and drink well and not have your face turned by a pretty face.”

Charles-Marie Widor and Marcel Dupré

On 31 December 1933, at age 89, Widor retired from his position at Saint-Sulpice. He complained of weakness in his arms, hands, and legs. As he reported to Dupré, “I have lost my technique.” Widor had been the organist for 64 years, and Cardinal Verdier made him an Honorary Organist. The Parish added two extra pedal stops to the organ which Widor had always wanted, but by 1934 he could no longer climb the steps to the organ loft.

Charles-Marie Widor: Suite Florentine (Janet Packer, violin; Orin Grossman, piano)

Final Composition

Despite his physical weakness, Widor continued to compose, and he produced his last organ work, the Trois Nouvelles Pièces, Op. 87 in 1934. He was still able to fulfill his functions at the Academié des Beaux-Arts, but his conducting at a performance of his Symphony No. 3 at Saint-Sulpice was described as “a real catastrophe. He no longer had the strength to lift his arm, but with a desperate effort, he insisted on going to the end.” The paralysis in his right arm was starting to present some real concern.

Cavaillé-Coll organ at Saint-Sulpice in Paris

When Widor met Albert Schweitzer, back again from Africa, he reported that “Widor’s right arm is giving him much trouble.” Some sources suggest that Widor had suffered a stroke which paralysed the right side of his body, while Schweitzer concluded that Widor was suffering from “a very slow blood poisoning; the tissues no longer have the strength to renew themselves. I think that he could still live for about two years.”

Charles-Marie Widor: Trois Nouvelles Pièces, Op. 87 (Thomas Trotter, organ)

Final Achievements

Widor was a man of great culture and learning, and he was elected Permanent Secretary of the Académie des Beaux-Arts in 1914, and in 1921 he founded the American Conservatory at Fontainebleau. He remained as director until 1934 when the position was taken over by Maurice Ravel. In 1916, Widor introduced the idea of founding the Casa Vélazquez, a counterpart to the Villa Medicis, where French artists could study Spanish culture.

Charles-Marie Widor at Saint-Sulpice

King Alfonso XIII of Spain was highly supportive and selected the site in Madrid which was ceded to France. After much bureaucratic haggling, the project finally came to fruition in May 1935, and Widor personally attended the opening ceremony. Alongside his doctor Lereboullet and wife, Widor even managed to create an atmosphere of political calm under the looming storm clouds of the Spanish civil war. This was Widor’s last major public appearance, as he was confined to this house for the final 18 months of his life.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Charles-Marie Widor: Chansons de mer, Op. 75 (Michael Bundy, baritone; Jeremy Filsell, piano)