Like no other conductor, Christian Thielemann’s artistic vision seems to divide the musical world. While his flamboyant interpretations are frequently the target of a hostile musical press, musicians and concertgoers appear to love him. Conservative in his musical and political views and unapologetically outspoken, Thielemann’s demeanour and interpretations are characterised by an extraordinary intensity, attributes that increasingly seem out of touch in a social media-addicted society.

Christian Thielemann Conducts Wager’s Prelude and Love Death from Tristan

West-Berlin

Christian Thielemann as a boy

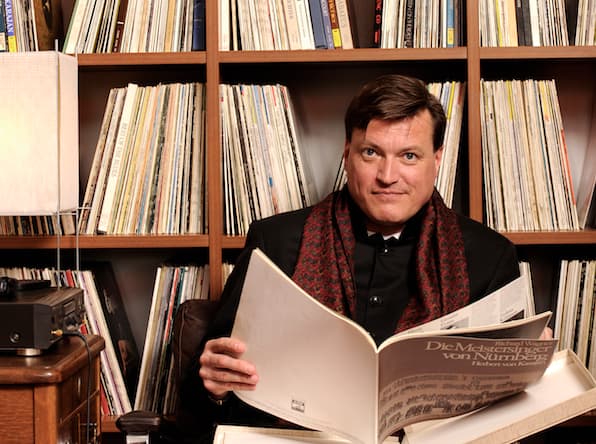

Born on 1 April 1959 in Berlin-Wilmerdorf, Christian Thielemann was surrounded by music as far back as he can remember. His father Hans Thielemann was a managing director of a West German iron trading company, and he had perfect pitch, just like his father Georg Thielemann. His mother Sybille came from an esteemed Pomeranian family of military officers, and she worked as a pharmacist. Both parents were accomplished pianists and they owned an extensive collection of records.

Thielemann grew up in West-Berlin, but almost half of his family lived in the former East Germany. He remembers, “when I was a little child standing at the Berlin Wall, I always wondered about people who said, we have to accept that it’s two countries, two nationalities. I never understood that. East Germany even tried to tell us that Bach was the first socialist. It was a tragedy, and so silly that one was forced to laugh!”

Anton Bruckner: Symphony No. 5 in B-Flat Major, WAB 105 (1878 version, ed.R. Haas) – II. Adagio, sehr langsam (Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra; Christian Thielemann, cond.)

First Impressions

Christian Thielemann

Christian Thielemann also has perfect pitch, and he learned to sing before he could talk. His mother remembered that she would sing lullabies to her son, and Christian would sing back the melody at the age of one. His mother cautiously noted in her diary, “he seems to have musical talent.” Christian quickly started to explore the family piano, and at the age of five, he started formal piano and violin lessons.

His real love, however, was orchestral music. His parents had season tickets for the Berlin Philharmonic, and the young boy was immediately fascinated by the colours and the flow of the music. And it seems, he was already fire and flame for the music of Richard Wagner. At that time, Christian thought that the conductor was a laughable figure. He asked himself, “what is all this supposed to mean, why is the conductor clenching his fists like he is obsessed?”

Robert Schumann: Symphony No. 3 in E-Flat Major, Op. 97, “Rhenish” – III. Nicht schnell (Dresden Staatskapelle; Christian Thielemann, cond.)

Political Correctness

Apparently, Thielemann was fascinated by slow movements. “Fast is easy,” he thought, “everybody can do that. But the slow movements are really difficult because you have to fill it with ideas, colours, and nuances.” Looking for musical depth, Thielemann decided to learn viola and he tried to teach himself how to play the organ. His piano teacher was decidedly unhappy, and his parents put a stop to his dreams of becoming an organist.

As a teenager, Thielemann was entirely focused on music, practising the piano, the viola, and studying any and all orchestral scores that he could get his hands on. He obsessively attended concert and opera performances, and “I never played football or listened to the Beatles,” he remembers. Thielemann grew up in a generation that hated most things German, and that included music and Richard Wagner. Thielemann would never share these kinds of sentiments and intuitively rebelled against all forms of political correctness.

Johannes Brahms: Tragic Overture, Op. 81 (Dresden Staatskapelle; Christian Thielemann, cond.)

Conducting Competition

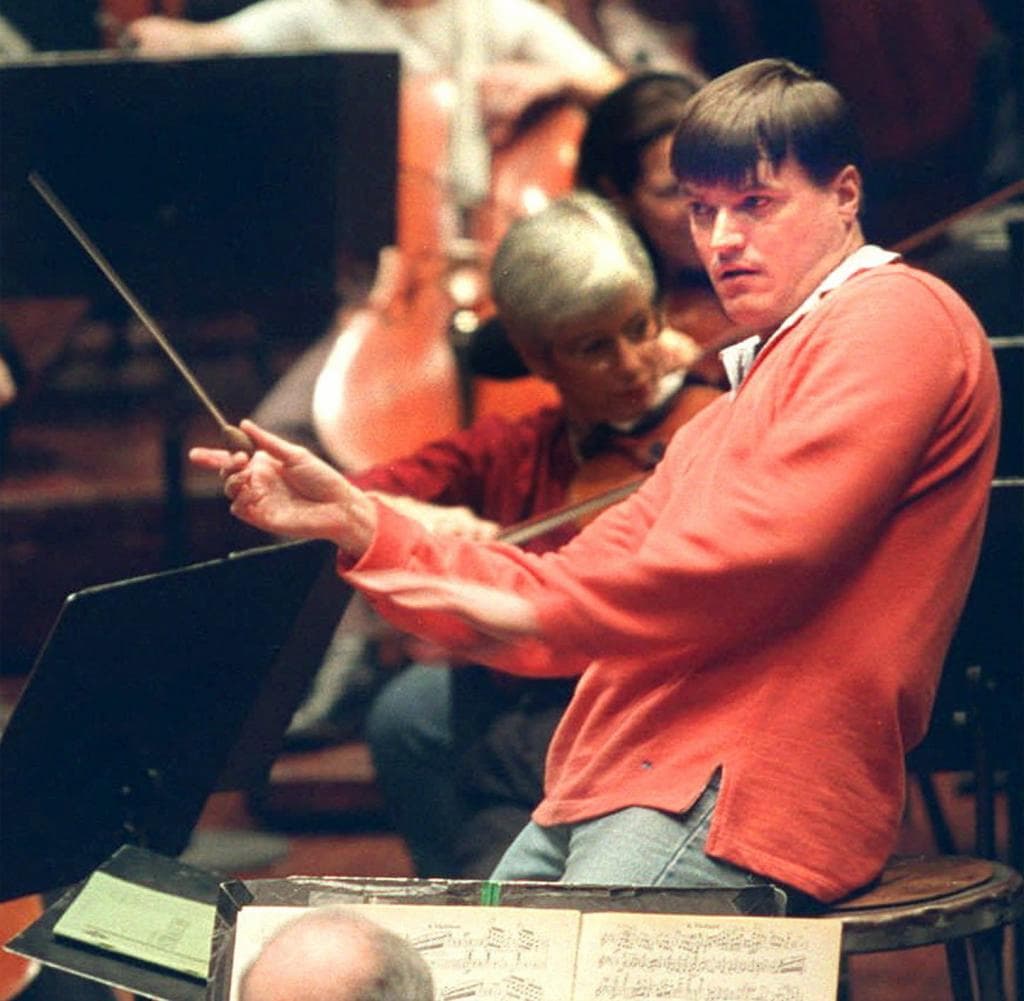

Thielemann received his piano diploma at the Berlin Conservatory, and he entered the Academy of the Berlin Philharmonic as a violist. Simultaneously he took conducting lessons with Hans Hilsdorf and secured a job as an accompanist at the German Opera, in Berlin. One year later, he assisted Herbert von Karajan in Salzburg. And it was Karajan who encouraged him to enter the Karajan conducting competition in 1985.

Members of the jury included Wolfgang Stresemann, director of the Berlin Philharmonic, Herbert von Karajan, Kurt Masur and Peter Ruszicka. The examination work was the prelude to “Tristan,” and Thielemann was one of 26 competitors. During the allotted time of 20 minutes, Thielemann worked in great detail on improving the orchestral sound and only managed to make it to measure 19 or 20. Thielemann remembers, “I got disqualified because I did not make it to the end of the score.” Fortunately, Herbert von Karajan had already seen his potential.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

I go to a lot of concerts, and I’ve seen every great conductor live. So I can say that when you see Christian Thielemann live, you can see that this man is a major force in music. I always say that he doesn’t hold a baton, he holds a magic wand. I’ve seen him conduct Beethoven, Mendelssohn, Brahms, Wagner, Bruckner, Mahler and Strauss. When he conducts, you can see and hear every note of every instrument in the piece. You are drawn into the music, guided by his magic wand. I even agree with his political incorrectness and his confrontational attitude towards the media. Happy birthday, Herr Thielemann, and I hope to see you often in Berlin.

Hi Elsa,

I love Thielemann very much, but where I can learn his conducting languages? Espesially I need to know what does it mean than Thielemann’s both hands move down following stronly move up? Is it the latter half or just the stress only. Point out or recommend references to me via my email address, Thanks.

Gary