Listen to the music of Jean-Baptiste Lully, Marc-Antoine Charpentier, Michel-Richard Delalande, François Couperin and Jean-Philippe Rameau, and you enter a world of elegance, ornamentation and artful rhythm. Most of all, as scholar James Anthony noted, French Baroque music “speaks of the dance in all its guises as does no other music.” At the heart of this distinctive style lies the performance practice of notes inégales—a technique where even note values are performed with a slight inequality, infusing the music with a sense of graceful movement.

François Puget: Portrait of several musicians and artists, traditionally said to include Jean-Baptiste Lully and librettist Philippe Quinault

The performance convention of notes inégales was described in more than 60 treatises and instructional manuals of the time, starting with Jean Rousseau in 1687 and continuing as late as Jean-Jacques Rousseau in 1768, when its use was likely waning. In the words of Étienne Loulié in 1696, “Les Notes égales se jouent inégalement” (“Equal notes are played unequally”). He went on to describe four ways this inequality could be applied. Typically, within a steady beat, a performer would elongate a first note and shorten the second. But by how much? This was left to the discretion of the musician.

This inequality was not explicitly notated in the music but was instead understood by performers of the time as an inherent part of the musical language. The decision whether to apply inequality, as well as its degree, depended on meter, tempo, character of the music and— most elusively—good taste. One contemporary writer said, “Expression consists principally in knowing what notes are equal or unequal.”

Performance of Jean-Baptiste Lully’s opera Alceste in the Marble Court at Versailles on 4 July 1674

To illustrate the most common use of notes inégales, listen to two performances of the Rondeau from Suite of Fanfares of Jean-Joseph Mouret, famously known as the theme of the television series Masterpiece Theatre (now Masterpiece). First, here is a recording from 1963, made before most musicians were aware of the convention.

Jean-Francois Paillard leads the Paillard Chamber Orchestra,

with Maurice Andre and Marcel Lagorge, trumpets

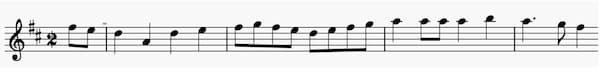

Theme, as notated:

In contrast, this 2023 recording employs period instruments and uses notes inégales after a series of introductory drumrolls:

Barocktrompeten Ensemble Berlin

Theme, as performed:

One of the key challenges for performers today is determining when and how to apply notes inégales. While historical sources provide general guidelines, they often leave room for interpretation. The many treatises, as well as musical cylinders for clocks and other mechanical devices, offer clues, but along with the evidence of changes over time, this direction is often conflicting. Compounding the complexity is the question of whether to apply the practice to non-French music. Musicologists have clashed for generations about notes inégales, and by no means has everything been settled.

What is clear is that during the French Baroque, rhythm was not merely a matter of mathematical precision but was imbued with a sense of movement and gesture. This approach reflects the broader cultural values of the time, which prized elegance, refinement, and a natural, unforced expressiveness. The use of notes inégales is just one example of how performers of the era breathed life into French music.

A performance of Rameau’s La princesse de Navarre on 23 February 1745 in the theatre of the Grande Écurie, Versailles,

as part of the celebrations of the marriage of the dauphin Louis to Maria Teresa of Spain.

The revival of this practice began as early as 1915 when the instrument maker Arnold Dolmetsch delineated performance practices in his book, The Interpretation of the Music of XVII and XVIII Centuries Revealed by Contemporary Evidence. After World War II, numerous scholars influenced the historically informed performance (HIP) movement. Yet until the 1970s, most recordings of French Baroque music featured sluggish tempos, modern instruments and the literal performance of note values that ignored this research. The French Overture that begins this 1968 recording of Jean-Baptiste Lully’s Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme is a typical example:

Lully : Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme, LWV 43

Just five years later, Gustav Leonhardt and La Petite Bande recorded the same music with period instruments, double-dotting the overture.

Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme – Comédie-Ballet, LWV 43: Ouverture

With the rise of the Classical style in the late eighteenth century, the practice of notes inégales quickly faded. The new aesthetic emphasized clarity, homophonic textures and symmetrical phrasing, making strict rhythmic precision more desirable. More than two hundred years later, however, musicologists and performers have revived this practice, bringing fresh energy and elegance to French Baroque music. While the great French composers of the era are still underappreciated relative to their Italian and German counterparts, their music is at last being heard with vitality and spirit of dance that originally defined it.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter