When musicians and composers get together to have a little brainy fun, they generally turn towards counterpoint. But not just any counterpoint, as composers throughout the ages have looked towards imitative counterpoint as practiced in canons and rounds. So, what is the actual difference between the two? A “round” is a limited and simple type of canon in which each voice enters after a specified interval of time at the same pitch, using the same notes. This type of canon theoretically has no ending, as it may continue repeating indefinitely. If you quickly grab a couple of friends and sing through “Row, row, row your boat,” “Frère Jacques,” or “Three Blind Mice”, you quickly know how a “round” works. This type of music was first named in England in the 16th century, but the musical practice goes much, much further back. The oldest surviving round in English dates from the 13th century, and it celebrates the coming of summer. Scored for four voices plus two bass voices—either sung or played instrumentally—it is a marvel of medieval musical ingenuity.

Sumer is icumen in

Anon: Sumer is icumen in (Summer has come) 13th century (John Potter, vocals; Dufay Collective)

Canons, by definition, tend to be slightly more complicated. Like a round, they sing or play the same music starting at different times. However, the original musical line in a canon can be imitated at any given time and any melodic interval. In addition, when a voice finishes its part in a round, it will start again from the beginning; in most cases, that is not true of canons, as these musical marbles can continue freely. Let’s demonstrate this bit of music theory with a relatively simple and highly popular canon.

Pachelbel’s Canon in D

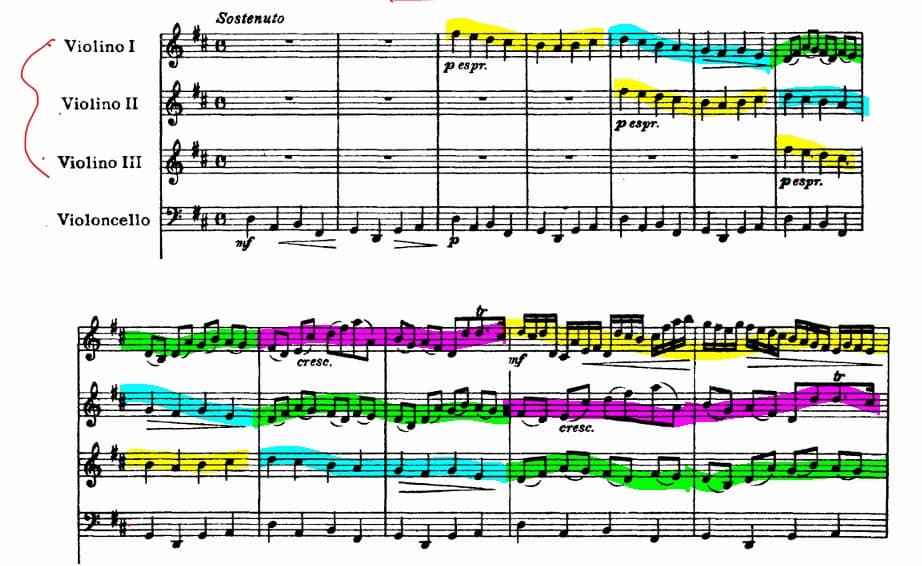

Composed by the German Baroque composer Johann Pachelbel sometime between 1680 and 1706, it achieved pop status in the late 20th century. It can be heard at weddings, funerals, graduations, and in commercials of all kinds, and that also includes background music in airports, malls, and toilets. Pachelbel’s Canon lingered in obscurity for centuries until it was first recorded in 1968. It is an accompanied canon for three violins and basso continuo. The canon unfolds successively in the three violins in unison. And if you listen very carefully, you will also hear that the basso continuo—always consisting of at least two instruments—plays a repeating bass pattern known as a ground bass or ostinato. In due course, the combination of the three-voice canon and the ostinato ground undergoes a number of delightful variations.

Johann Pachelbel: Canon in D Major

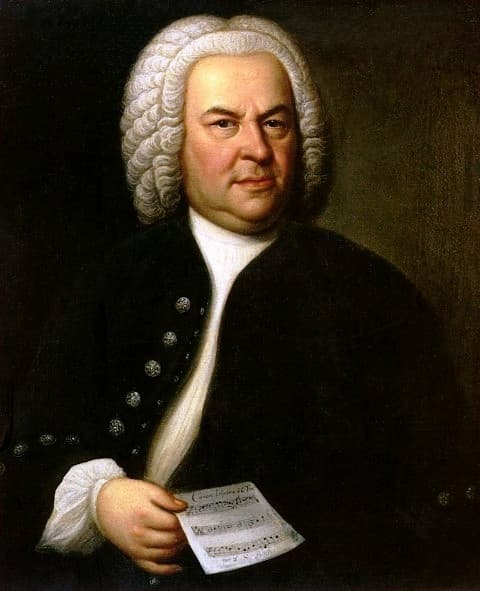

During the final decade of his life, J.S. Bach became musically preoccupied with canons and fugues. In June 1747, he was admitted to a society devoted to musical scholarship founded by Lorenz Christoph Mizler. Mizler was a physician, historian, mathematician and composer, and his “Corresponding Society of the Musical Sciences” was established to enable musical scholars to circulate theoretical papers to further musical science by encouraging discussion—what a concept! To celebrate his admission as the fourteenth member, Bach presented a portrait painted by Elias Gottlob Haussmann, in which the composer holds a copy of his “canon triplex a 6 voci,” BWV 1076.

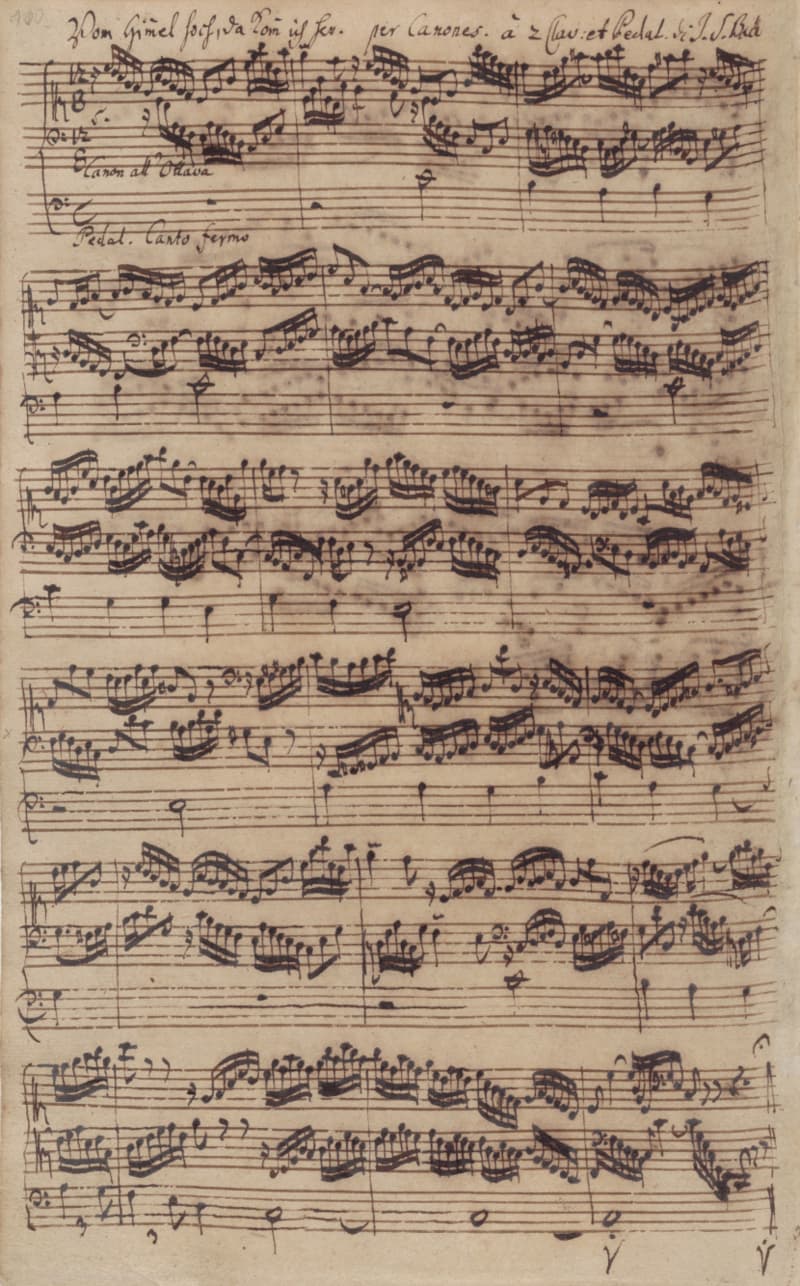

J.S. Bach’s Canonic Variations on “Vom Himmel hoch”

But what is more, Bach also submitted a set of five variations in canon for organ on the Lutheran Christmas hymn “Vom Himmel hoch.” Bach explores the canonic possibilities of that hymn to never-matched perfection. Variation 1 sounds a canon at the octave between the right and left hand, with the chorale in the pedal, followed by a canon at the fifth with the chorale once again in the pedal. In further variations, the chorale itself becomes the canonic voice, sounding at the interval of a seventh and in augmentation. The final variation is simply astonishing. The choral becomes a canon at the sixth, inverted—upside down—between the right hand and the left. Then we hear the canon at the third, followed by canons at the second and the ninth. And if that wasn’t enough, Bach musically also signs his name B-A-C-H. But don’t be distracted by all this complexity, as “these variations are full of passionate vitality and poetic feeling… The experiences of a fruitful life of sixty years are interwoven with the emotions of his earlier year.”

Johann Sebastian Bach: Canonic Variations on “Vom Himmel hoch” BWV 769

Canons come in all forms, shapes and musical styles, and in this series I will present, as the title implies, my favorite canons and other musical puzzles. In a puzzle canon, one voice is generally notated and the rules for determining the remaining parts and the time and musical interval of imitation must be guessed. Frequently, the composer provides clues, hints, cryptic symbols or texts in a variety of languages to allow the musician to arrive at a proper musical solution.

Schoenberg’s 4 Part Puzzle Canon

Countless composers have fashioned puzzle canons, and that includes Arnold Schoenberg. Rudolph Ganz, pianist, composer and music director of the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra and director of the Chicago Music College had contacted Schoenberg about an academic opening. Although they could not reach an agreement, Schoenberg sent him a puzzle canon with the words, “It’s too bad that I can’t come to Chicago.” In this version, the perpetual canon is taken by a saxophone quartet.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Arnold Schoenberg: 4 Part Puzzle Canon for R. Ganz “Es ist zu dumm” (Marcus Weiss, saxophone; Jean-Michel Goury, saxophone; Pierre-Stephane Meuge, saxophone; Sergio Bertocchi, saxophone; Jürg Henneberger, cond.)