Janet Horvath performing

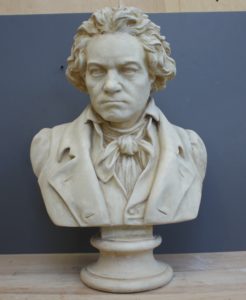

I grew up with Beethoven. From my earliest years I remember the scowling white plaster bust on our piano, and the divine sounds of the Moonlight sonata rising from my mother’s piano studio. My father, a cellist, when he didn’t have an orchestra concert, played string quartets and trios in our living room, after my brother and I had supposedly gone to bed. I remember the irresistible urge to sneak out to the railing to spy on them rehearsing the glorious music.

The Beethoven String Quartets were played with an unusual ardor. A towering figure in our household, the quartets are ground-breaking and wonderful works. But there was an underlying reason, I later learned.

Joseph Haydn playing quartet

My father, a Holocaust survivor, performed extensively in Europe before the Second World War even though he was barely in his twenties. Because he was Jewish, he was not allowed to become a permanent Budapest Symphony Orchestra member. Jewish musicians had severe challenges when the Third Reich came to power in Germany in the 1930s. By 1933 the “Law for the Restoration of the Civil Service” was enacted in Germany, excluding all racial and political enemies of the state—in other words anyone non-Aryan. Jewish conductors, singers, music teachers, composers, and administrators were fired. Musicians, dismissed from orchestras, and forbidden to perform with “Aryan” groups, formed ensembles comprised solely of Jewish performers—so they could continue to play music; so Jewish audience members who were no longer allowed to attend orchestra, opera, or theater events, could hear music.

The Nazis, aware music has significance and power, proud of the history of noteworthy German composers Mozart, Bach, Beethoven, Haydn, Schubert, Bruckner, Wagner, determined their music was to be preserved and sheltered, and not defiled. Soon Jewish musicians were forbidden to perform the works of these composers, especially the music of Beethoven.

When Beethoven’s chamber music resounded from our living room I sensed a singular meaningfulness and it stirred me.

The sixteen string quartets epitomize the unprecedented complexity, energy, and intensity of Beethoven’s music. The works are grouped by time-periods. The Op.18 quartets, were composed during 1800 – 1801 and consist of six quartets. They are close in form to Haydn’s quartets but already show Beethoven’s imagination and originality.

String Quartet No. 4 in C Minor, Op. 18, No. 4 – I. Allegro ma non tanto (Miró Quartet)

IV. Allegretto – Prestissimo (Miró Quartet)

Beethoven’s so-called middle period produced some of the most astonishing works in existence. Between the ages of 35-40 Beethoven wrote his middle quartets, the three quartets of the Op. 59 series, which were dedicated to and commissioned by Russian Ambassador to Vienna Razumovsky, an accomplished musician himself, the Op. 74 Quartet, The Harp so named because of Beethoven’s use of pizzicato, and Op. 95 the Serioso. These pieces show increased drama, lyricism, and a breaking away from classical forms and structure.

String Quartet No. 10 in E-Flat Major, Op. 74, “Harp” – I. Poco adagio – Allegro (Tokyo String Quartet)

Beethoven

The only way to describe the late string quartets is to say they are profound, contemporary- sounding, and enigmatic. These works push boundaries structurally and emotionally, and inspired subsequent composers including Wagner, Stravinsky, and Bartók— Op. 127, 130, 131, 132, 133, the massive Grosse Fugue published separately, and the last piece Beethoven ever wrote, his Op. 135 quartet from 1826—transcends everything that had come before. Beethoven changed not only how music was written. He changed how people listened to music.

Finally, it was my turn to learn a Beethoven string quartet. From the first pulsating notes of Op. 18, No. 4, in C minor, it’s pathos and restlessness thrilled me. Beethoven’s characteristic misplaced accents and sforzandos on offbeats, begins almost immediately with the three lower instruments playing big chords. The first violin interjects. This strategy keeps us slightly off-kilter. We are taken on a musical journey through various moods ranging from the dramatic, the mysterious, the intense. Some unusual compositional techniques are implemented—the entire quartet is mainly in C—minor and major. There is no slow movement, but instead, a flirtatious scherzo, which begins to probe fugal episodes. The last movement is a dramatic prestissimo in Rondo form but nothing like those of his predecessors. Towards the end the tempo hurtles forward and with some surprise pauses, ends in a fury. Playing this piece reinforced my love affair with Beethoven’s music.

The first time I performed Beethoven Symphony No. 5, with the Toronto Youth Orchestra, at all of age fifteen, I remember feeling very insecure about the lilting solo for the cello and viola sections at the beginning of the second movement. When my father instructed me to start the upbeat downbow at the tip of the bow, and to play virtually all of the theme on the D string, resulting in the requisite dolce, sweet, mellow sound. It was a revelation.

Symphony No. 5 in C Minor, Op. 67 – II. Andante con moto (Zagreb Philharmonic Orchestra; Richard Edlinger, cond.)

I’ve lost count how many times I’ve played and recorded the nine symphonies. The Minnesota Orchestra programmed the monumental Symphony No. 9 nearly every season, often to ring in the New Year. Once, German Conductor Klaus Tennstedt was on the podium. “It must be. You must be! Pianissimo.” he cajoled. The Ode to Joy theme, proclaiming universal brotherhood, is played first almost inaudibly by the cellos and basses. Our music picked up a little breeze and the page flipped over. Not daring to breathe let alone disturb the undulating melody by turning the page back, we played the entire two pages from memory.

Symphony No. 9 in D Minor, Op. 125, “Choral” – IV. Finale: Presto – Allegro assai (Vienna Symphony Orchestra; Herbert von Karajan, cond.)

My father and I were fortunate to play Beethoven throughout our long careers. What’s uncanny about Beethoven is whenever we perform any of his five cello sonatas, his piano trios, and within the orchestra, the sublime violin concerto, the five piano concertos, or the nine symphonies, we discover something new—profound concepts to express in fresh ways.

Of the many times I performed Beethoven Cello Sonata in A major, a recital in Canada stands out. It meant so much to be able to play this beloved composer on the occasion of my father’s 80th birthday. I dedicated the performance to him and to anyone who has been or is now being prevented from making music. Beethoven, 250 years after his birth, continues to be relevant.

Beethoven: Cello Sonata No. 3 in A major, Op. 69 – II. Scherzo. Allegro molto

Beethoven: Cello Sonata No. 3 in A major, Op. 69 – III. Adagio cantabile – Allegro vivace

Marvelously passionate playing. Two consummate artists.Oh I love the cello!!