Carl Vollrath: Pollock’s Pictures

As a painter, Jackson Pollock (1912–1956) broke all the rules. He pushed abstract expressionism to dizzying heights. Enjoying both fame and notoriety during his lifetime, his works continue to challenge us to see how he did, with line detached from colour, and creating a new way of defining pictorial space.

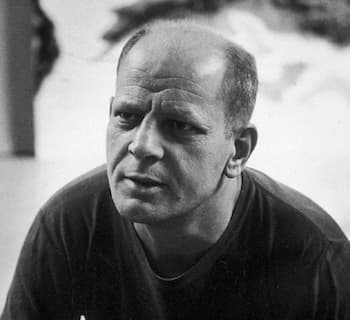

Jackson Pollock

After seeing an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in November 1939 on 40 years of Picasso, which concluded with Guernica, Picasso’s striking anti-war mural, Pollock reconsidered European modernism and began to create his own ‘semi-abstract totemic compositions’.

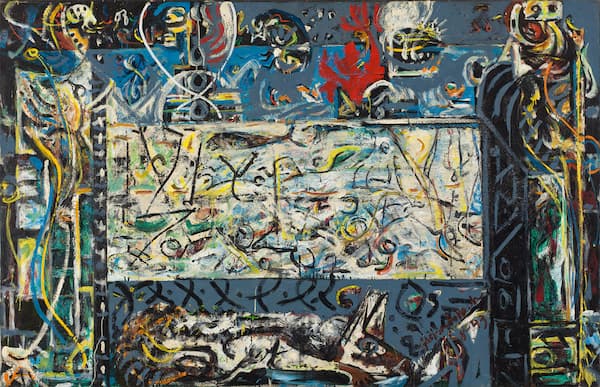

Pollock’s 1943 work, Guardians of the Secret, shows the influence of Picasso’s Guernica, in its division of the space into separate sections. The work is large, standing 4 feet high and over 6 feet wide. At each side of the painting stand tall vertical figures. The left figure has a skull-like head and bones make up its body. The right-side figure is clothed in black wearing a head covering, which could be a mask, a helmet, or just cloth.

At the bottom edge of the painting is a dog-like figure, facing to the right with paws extended. We can see ears, a single eye, and its long snout. Above the dog is a lighter coloured area, brightened by the use of yellow, white, and green, with black and red/orange for emphasis. One writer on this painting suggested that this area could be ‘a tapestry, a scroll, or a shroud marked by hieroglyphics’.

Across the top of the painting are abstract symbols with some suggestions of realization: is the bright red at the right of centre a rooster? Is the curved figure to the left centre the figure of Kokopelli, the flute-playing god of the Native Americans? Is the figure to the left of Kokopelli a scarab? They are all guardians of the secret.

Jackson Pollock: Guardians of the Secret, 1943 (SFMOMA)

American composer Carl Vollrath (b. 1931) used three Pollock paintings as the inspiration for his chamber work, Pollock’s Pictures, for clarinet, cello, and piano. We’re not hearing the Pollock painting, but rather Vollrath’s interpretation of the painting. We’re not getting the complexity of the painting, but rather a reading that captures first one aspect, then another.

Carl Vollrath

Carl Vollrath: Pollock’s Pictures – I. Guardians of the Secret (Rane Moore, clarinet; Jonathan Miller, cello; Randall Hodgkinson, piano)

Next is a work by Pollock from 9 years later, Convergence. Pollock has firmly departed from any idea of representation and is fully into the abstract. This is one of Pollock’s most famous works, described as ‘a collage of colours splattered on a canvas that created masterful shapes and lines that evoke emotions and attack the eye’. The work is enormous, 7.8 feet by 12.9 feet (237.5 cm x 394.7 cm). and is a combination of his drip method and brushstrokes. All the elements of colours, lines, textures, lights, and contrasting shapes come into play.

Jackson Pollock: Convergence, 1952 (Buffalo AKG Art Museum)

Vollrath’s Convergence movement isn’t full of the textures of the art: piled-up and overlaid lines are not in the music. Instead, the three voices each have their own tessiture and style. One might almost imagine the clarinet’s wavering line as the oranges or yellows, the cello and the while, and behind it all the complexity of the piano’s black.

Carl Vollrath: Pollock’s Pictures – II. Convergence (Rane Moore, clarinet; Jonathan Miller, cello; Randall Hodgkinson, piano)

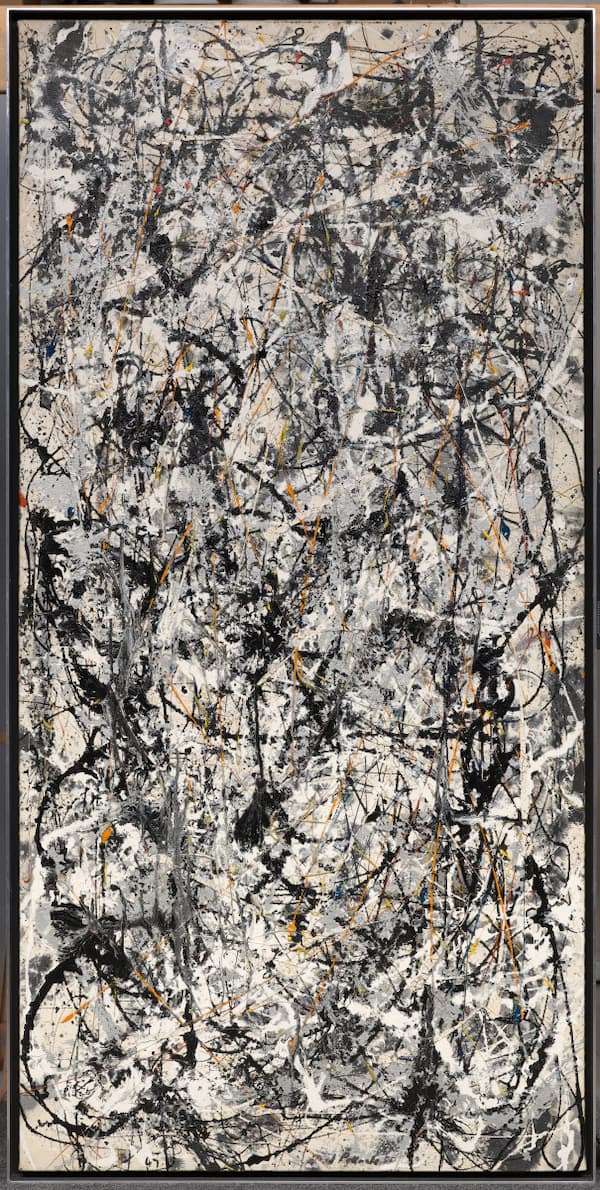

Cathedral, a drip painting from 1947 at first seems to be all black, white, and grey, but then you start to see the smaller colours – red and yellow. The size is a more manageable 6 feet x 3 feet (181.61 cm x 89.06 cm).

Pollock famously said about his drip works: ‘On the floor, I am more at ease. I feel nearer, more a part of the painting, since this way I can walk around it, work from the four sides and literally be in the painting’. One writer saw the title, Cathedral, as a reference to the painting as an evocation of ‘the soaring heights and intricate details of a Gothic cathedral’s architecture’.

Jackson Pollock painting in 1950

Cathedral is considered one of Pollock’s ‘Action Paintings’ where the physical process of making the work of art is as important as the art itself.

Jackson Pollock: Cathedral, 1947 (Dallas Museum of Art)

In the final movement, we’ve slowed the speed to one that encompasses reflection and meditation.

Carl Vollrath: Pollock’s Pictures – III. Cathedral (Rane Moore, clarinet; Jonathan Miller, cello; Randall Hodgkinson, piano)

These works all appear on a 2021 album of Vollrath’s works entitled Transit Voices: Underground Landscapes, where the composer used Andrew Robinson’s book Lost Languages: The Enigma of the World’s Undeciphered Scripts as a springboard for his thoughts. The existential questions, such as who we were before history and what we share with those ancestors, are central to his thoughts. Vollrath goes on to say ‘Most of human history is unknown to us, and all we have are underground landscapes. The meaning of words has changed throughout time— what did the word “love” mean 5,000 years ago? How much of their meanings are still with us today? The works here are an attempt to explore the hidden possibilities of humans’ past existence. One might ask: what about Pollock’s paintings? Are they not the most organic paintings in modern history? Since music is an abstract art, we can similarly conceptualise its meaning.

In working through his interpretation in view of Pollock’s paintings, and in choosing works both before and after his change in style to drip painting, Vollrath gives us his reading of Pollock. He’s not caught up in the surface action, but the support thought. His first movement, Guardians of the Secret, isn’t about the guardians, but about the secret. In Convergence, each instrument takes its own way through the work. Cathedral is about the centuries and millennium of thought that any cathedral building embodies. This may not be the way you’ve ever ‘heard’ Pollock’s work, but Vollrath’s interpretation seems to follow the idea of his album title and look for the underground landscapes in Pollock’s creations.

With only three voices, Vollrath’s chamber work is lucid and clear, and he’s adept at using the wide range of the piano to prompt responses from the other two instruments, and, conversely, using the piano to support their statements.

In the 1950s, Jackson Pollock’s paintings provoked a flood of criticism and commentary. In Vollrath’s music, those paintings are the new normal, and let’s move forward. Don’t react to the surface, respond to the thoughts behind it all.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter