Wolfgang-Andreas Schultz: Maria Aegyptica

In this 16th-century statue of St. Mary of Egypt, we see her with her usual characteristics: Long flowing hair, in this case, worn to cover her body and three loaves of bread that she took with her when she went into the desert.

16th century statue of Mary of Egypt (Église Saint-Germain-l’Auxerrois) (photo by Mbzt)

In paintings, she’s often depicted as a tanned, emaciated figure, with her ribs showing and few clothes, in a desert setting. In the statue above, there are trees behind her; in Tintoretto’s painting, she’s also shown in a forest. Both forests and deserts represented uninhabited areas.

In this Russian icon of Mary, she’s shown in the center with her long hair and exposed ribs. In the bottom left corner, Zosimas of Palestine gives her his cloak to cover her nakedness, and in the bottom right corner, he finds her dead body.

Russian icon of St. Mary of Egypt, 18th century (Kuopio Orthodox Church Museum, Finland)

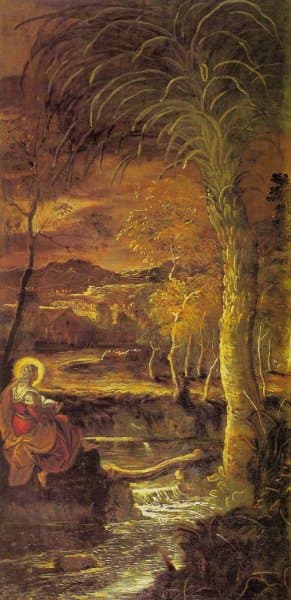

Tintoretto’s painting, known as St. Mary of Egypt or Santa Maria Egiziaca, was painted for the Scuola Grande di San Rocco in Venice as one of a pair of paintings.

Mary sits in the bottom left corner on a rock, separated from the background of a forest and stream at night. The moonlight catches the water and the high ground at the back of the picture. The brightness of her halo draws the viewer’s attention, as does her red dress. She’s fully clothed and holds a book; her back is to the viewer.

Tintoretto: St. Mary of Egypt, 1582 – 1587

(Venice: Scuola Grande di San Rocco)

Because of the lack of attributes for the typical depiction of Mary of Egypt, i.e., the long hair, the 3 loaves of bread, and the emaciated body, there is some doubt about the identification of the woman as really being Mary of Egypt. Nonetheless, that is the name that has come down to us in the Tintoretto works.

Mary of Egypt is a story of redemption from the 4th century. Mary started her life as a prostitute, fleeing her family in Alexandria to live a life of sexual depravity. Her goal was to have sex with as many men as possible, and she wound up on a boat for the Holy Land, with all the men on the boat as her sexual slaves. When she arrived in Judea, she attempted to enter a church but was barred by an invisible force. Her impurity was preventing her entrance, so she prayed to an icon of the Virgin Mary, asking for forgiveness and promising to give up the world. She was then able to enter the church. When she left the church, the icon instructed her to cross the Jordan River. She crossed the river to enter the desert where she lived as a hermit in penitence. She brought with her three loaves of bread, and when they were finished, she ate only what she found in the wilderness.

She met Zosimas of Palestine and asked him for his cloak to cover her. The story of Mary comes down through Zosimas’ records. He met her, and she told him her life story while he was in the desert for the 40 days of Lent. She asked him to meet her again in a year and to bring her Holy Communion, which he did. The third time he tried to meet her, he found her dead and buried her.

Zosimas’ story, which existed only in the oral tradition around Palestine, was recorded in the 7th century by Sophronius, Patriarch of Jerusalem from 634 to 638. The Vita of St. Mary of Egypt is traditionally read on the fifth Thursday of Lent.

Tinoretto’s painting was the inspiration for German composer Wolfgang-Andreas Schultz (b. 1948) and his chamber work, Maria Aegyptica. Written for a string trio of viola da gamba, viola, and cello, the work, described as a Fantasy, picks up on the darkened Tintoretto landscape and gives us a somber picture.

Wolfgang-Andreas Schultz

Schultz has been described as ‘a melodist who thinks in images or scenes’, and we can hear that in this work. As in the story of Mary of Egypt, we also have the redemptive element, which emerges in the ending.

Wolfgang-Andreas Schultz: Maria Aegyptica (Bernd Musil, viola da gamba; Fridtjof Keil, viola; Angela Klotz, cello)

Schultz was a student of Györgi Ligeti and served as his assistant from 1977 to 1988. In 1988 he was appointed professor at the Hochschule für Musik und Theater Hamburg, retiring in 2016. Initially following Ligeti’s example of static sound surface composition with a compositional technique influenced by impressionism, he broke away from this and worked on his own evolutionary music aesthetics, in which innovation developed from tradition. His philosophical inquiries include the book Avantgarde, Trauma, Spiritualität: Vorstudien zu einer neuen Musikästhetik (Music, Trauma, Spirituality: Preliminary Studies for a New Music Aesthetic), where he attempts to include the spiritual dimension of man into the music history of man. He thinks beyond postmodernism. Maria Aegyptica fits into this aesthetic by looking at the life of a saint who redeemed her life and became one of the Desert Mothers, who is now commemorated by the Catholic Church as the patron saint of penitents.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter