Böcklin: “Selbstbildnis mit fiedelndem Tod (1872) (Berlin: Alte Nationalgalerie)

The Swiss symbolist artist Arnold Böcklin (1827-1901) was born in Dusseldorf and studied at the Dusseldorf Academy. His teacher sent him to Antwerp, Brussels, and Paris to study the old masters and develop his potential. In 1850, after a stint in the army, he headed for Rome and there found something more than the old masters of the north had given him – he discovered the power of using allegorical and mythological references in his work. Nymphs and naiads, the huntress goddess Diana, the Greek poet Sappho populated his work. He moved every few years between Italy and the north, working in Weimar, Basel, and Munich.

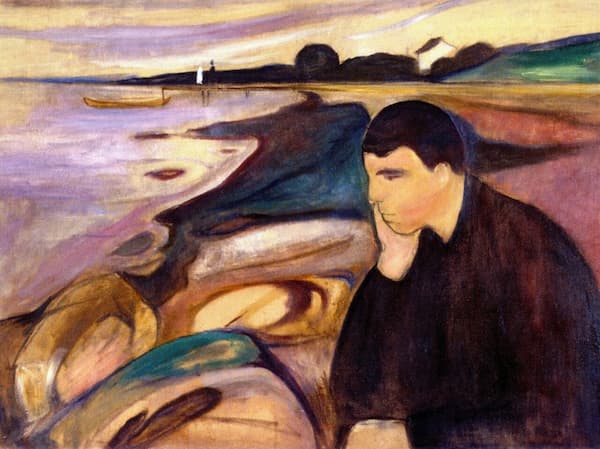

In 1872, he painted his Self-portrait with Death Playing the Fiddle (violin solo), which according to Alma Mahler, had been the inspiration for the second movement of Gustav Mahler’s fourth symphony. Mahler began working on the fourth symphony in the summer of 1899. The second movement is generally described as a Totendanz (Dance of Death). The Scherzo soloist is a violin, but tuned up one tone from the orchestra. This Scherzo movement is more than the usual Scherzo – Trio combination with the Trio being based on the traditional Ländler dance. The violin presents the character ‘Freund Hein’ (Friend Henry) who is a German medieval personification of Death. In his self-portrait with Death, Böcklin is looking at the viewer, but his attention is elsewhere as he has his head tilted to hear what Death is playing on his one-string violin. Originally, Mahler had headed this movement: ‘Death strikes up the dance for us; she scrapes her fiddle bizarrely and leads us up to heaven.’

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 4 – II. In gemächlicher Bewegung, ohne Hast (Polish National Radio Symphony Orchestra; Antoni Wit, cond.)

Böcklin: St. Anthony Preaching to the Fish (1892) (Kunsthaus Zurich)

Twenty years later, Mahler took up a different image from Böcklin as the inspiration for two further works. In a song cycle setting some of the anonymous texts from Des Knaben Wunderhorn (The Youth’s Magic Horn), collected by Achim von Arnim and Clemens Bretano, Mahler took an anonymous poem on St. Anthony preaching to the fishes as one text. The poetry of Des Knaben Wunderhorn, published in 3 volumes 1805 and 1808, collected children’s songs, songs of love, about soldiers, about wandering, and was a large part of the idealized folklore that was so important in the rise of Romantic nationalism in the 19th century. The Brothers Grimm began their fairytale collection under the guidance of Bretano, for example.

Mahler found the collection to be a particular point of inspiration and beginning with using the text in his Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen (Songs of a Wayfarer) song cycle of 1885. His larger song cycle, Des Knaben Wunderhorn (The Boy’s Magic Horn), begun in 1887, included one setting that was both from the Des Knaben Wunderhorn collection and also inspired by Böcklin: St. Antony Preaching to the Fish.

The story comes from the life of St. Anthony of Padua. He had travelled to Rimini to preach because it was supposed to be a ‘hotbed of heresy.’ The people of the city, as instructed by their leaders, ignored him. Anthony went down to the Marecchia River and began to preach to the fish, saying ‘You, fish of the river and sea, listen to the Word of God because the heretics do not wish to hear it.’ Thousands of fish gathered in rows to hear his words, as did the people of Rimini to see this miracle. The heretics Rimini were convinced by his words to return to the church and St Anthony was successful in his mission.

In his 1892 painting, Böcklin depicts one particularly attentive fish out of the water at the saint’s feet, while out in the river, the other fish line up with their heads out of the water to hear St Anthony’s words. Even the crabs have come out of the water and lift their claws to the saint. The dark panel below shows yet more fish in the water; these are not listening to St Anthony, but continue in their self-regarding ways, eating smaller fish. Behind the saint, in front of the city, we see a few figures of people watching the saint’s actions.

Mahler’s setting of the song is dry and mocking, setting up the heretical citizens of Rimini as being much less than the fish of the sea.

Gustav Mahler: Des Knaben Wunderhorn – No. 6. Des Antonius Von Padua Fischpredigt (Håkan Hagegård, baritone; Cologne Radio Orchestra; Gary Bertini, cond.)

In his second symphony, Resurrection, the third movement, was also inspired by the same Böcklin image of St Anthony and the fish. In the movement, which operates with the other middle movements as a kind of intermezzo from the larger questions of life, death, and future life that frame the symphony as a whole, Mahler creates scherzo filled with a variety of emotions. It’s full of uncertainty and despair, but, at the same time carries an optimism that is uplifting.

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 2 in C Minor, “Resurrection”: III. In ruhig fliessender Bewegung (Polish National Radio Symphony Orchestra; Antoni Wit, cond.)

Chronologically, Mahler wrote the second movement of his Symphony No. 2, wrote the Des Knaben Wunderhorn song, and then returned to the symphony, writing the third movement with its inspiration from the song and the image together. Mahler’s setting of the song is dry and mocking, setting up the heretical citizens of Rimini as being much less than the fish of the sea.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Very interesting . In fact many composers were inspired by artists or philosophers like R.Strauss. Thanks.