Jessica Krash: Be Seeing You

American composer Jessica Krash was commissioned by two Washington DC arts institutions, the National Gallery of Art and The National Museum of Women in the Arts to create a work based on 14 works of art about women.

Krash chose 14 images of very different women, ranging over 7 centuries in time and decades apart in their ages, in whom she read mixtures of emotions. She chose ‘mothers who look both peaceful and worried, young women both glamorous and awkward, a middle-aged woman who looks feisty yet tired’. She also imagined what these women did outside of their portraits. She saw Fragonard’s garden beauty as having a secret worry about the global economy. Max Ernst’s statue has a second life as a glamourous pop diva.

She opens the work with Modigliani’s Madame Amédée (Woman with Cigarette). Madame Amédée sits on a wooden chair, one arm crooked, the other holding a cigarette. Her eyes pitch down at the corners, and her lips seem to be pursed. Krash imagines her as an imperious woman who has been distracted by a few daydreams.

Amadeo Modigliani: Madame Amédée (Woman with Cigarette), 1918 (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art)

Jessica Krash: Be Seeing You – I. Amedeo Modigliani, Madame Amédée (Woman with Cigarette) (Jessica Krash, piano; The Sunrise Quartet)

Jane (née Fortescue Seymour), Lady Coleridge, was an artist who was the wife of the 1st Baron Coleridge. John Duke Coleridge was the great-nephew of the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge. He married Jane Fortescue Seymour in 1846, who was already an accomplished and noted artist.

Her self-portrait, painted in 1841 when she was 17, shows us a self-assured girl with her hair in the fashionable ringlets of the time. She holds her palette in her left hand, brushes at the ready, while her right hand sits in her lap. She’s dressed in a black coverall, doubtlessly to preserve her clothes. She looks out at the viewer with a quiet confidence that immediately makes her seem older than her 17 years.

Jane Fortescue Seymour, Self-portrait at 17, 1841

In her music, Krash looks beyond the surface and seems to capture all the uncertainty and excitement of a teenager.

Jessica Krash: Be Seeing You – II. Jane Fortescue Seymour, Self-portrait at 17 (Jessica Krash, piano; The Sunrise Quartet)

In the 14th century, Giotto’s explorations and innovations in art pushed artists into what would become the full Renaissance style. No longer stylised ideas, his Madonna figures start to take on more human qualities. She doesn’t sit and simply hold a child but engages it with a white rose (as a symbol of her purity) while his left hand firmly holds her index finger. She’s not yet a fully realised Renaissance woman; there’s something not quite right about the back of her jaw, and the child could be 3 months or 6 years old. But there’s a new three-dimensional character that points the way forward.

Giotto di Bondone: Madonna and Child, ca 1310–1315 (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art)

In her music, Krash places us in a scene of string assonance and piano dissonance…or perhaps it’s the other way around. The piece seems unsettled, questing, and yet, behind it all, there is solid support.

Jessica Krash: Be Seeing You – III. Giotto di Bondone, Madonna and Child (Jessica Krash, piano; The Sunrise Quartet)

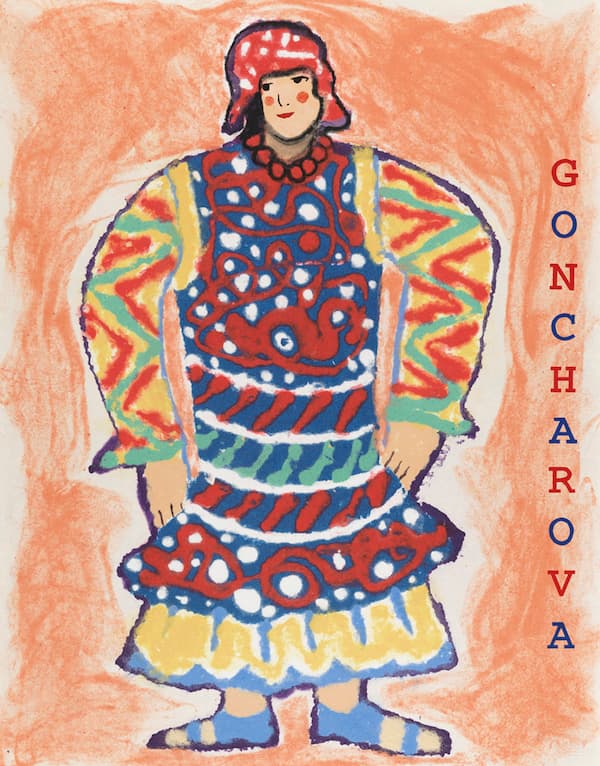

About as far from the refined work of Giotto as possible is Canadian artist Mariam Schapiro’s silkscreen entitled Goncharova. Her head is too small for her body, her arms too long and unmatched, and her feet barely seem able to support the body. But the colours are bright, the patterns exuberant, and every element of the body’s covering (torso, arms, underskirt, and hat) is distinctive.

Schapiro was an important member of the feminist art movement and worked with Judy Chicago (known for her installation The Dinner Party) at the California Institute of Arts. This print is from the portfolio collection Delaunay, Goncharova, Popova and Me (Pyramid Atlantic, 1992).

Schapiro wanted work by women artists and by women in their home arts to be recognised. Quilting, embroidery, and appliqué were more than just crafts and became part of what she termed ‘femmage’, creating a continuity between high art collage and works made by anonymous women. The title refers to the Russian avant-garde artist Natalia Sergeevna Goncharova (1881–1962), who had a successful career in fashion and design, creating the costumes for Serge Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes productions of The Golden Cockerel and The Firebird.

Miriam Schapiro: Goncharova, 1992 (Philadelphia: Museum of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts)

Krash’s Goncharova carries the sharp percussion of a Stravinsky ballet and the harmonies and melodies of Russia.

Jessica Krash: Be Seeing You – IV. Miriam Schapiro, Goncharova (Jessica Krash, piano; The Sunrise Quartet)

Lotte Lassertein’s Morning Toilette carries us back to the many familiar paintings of women engaged in their intimate lives. Renoir, for example, painted women in their daily routines, combing their hair, bathing, and other activities. Japanese artists also showed women at their toilette. Thirty years later, however, the soft-edge impressionism of Renoir is replaced with a more realistic image. It’s unflattering and closer to German realism than French impressionism. The sensuality of the 19th century has been exchanged for a less idealised view: Our subject (shown life-size) shows the effects of the sun on her face and hands, her hair is bluntly cut and falls across her view. Her clothes are old, and her slippers are worn.

Lotte Laserstein: Morning Toilette, 1930 (Washington, DC: National Museum of Women in the Arts)

The music seems to evoke the daily drudgery of spot bathing in cold water. No luxurious warm water soaks here, it’s just clean up and go off to the day’s tasks.

Jessica Krash: Be Seeing You – V. Lotte Laserstein, Morning Toilette (Jessica Krash, piano; The Sunrise Quartet)

Created in a folk-art style, Cherries in the Sun (Siesta) by American painter, illustrator, and designer Doris Lee brings out a question of place. Why is the bed outside? Is this a dream or reality?

On a hot day, our subject is lying on top of a colourful quilt, holding a fan. To her side, on a stump, is a bowl of cherry pits and a red beverage in a wine glass. On the ground, her book has been cast aside, along with her stylish shoes, and a bowl of cherries awaits. Birds perch on the bedstead and hide underneath, while a rooster has taken over the foot of the bed.

Doris Lee: Cherries in the Sun (Siesta), ca. 1941 (Washington, DC: National Museum of Women in the Arts)

Krash’s music picks up on the bird images and their repeating chirps and cries. Yet, our figure dreams in the sun, waiting to summon enough energy for one more sweet fruit.

Jessica Krash: Be Seeing You – VI. Dorris Lee, Cherries in the Sun (Siesta) (Jessica Krash, piano; The Sunrise Quartet)

In Matisse’s portrait, a woman with pale skin wears a turban and a goldenrod-yellow jacket. The background colours pick up on the painting colours. This is post-Impressionism, smoothing out the rough edges of fauvism and using contrasting colours to set a subject in place.

Lorette was an Italian model working in Paris and Matisse used her in a number of works in 1916 and 1917. This style of painting was new to Matisse and through his Lorette series, Matisse was able to develop a richer painting style, in contrast with his earlier paintings with their jarring colours, and to bring the viewer into a closer connection with the subject.

Henri Matisse: Lorette with Turban, Yellow Jacket, 1917 (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art)

Lorette, with her head bound in a turban and her slightly askance look at the viewer, keeps her thoughts to herself while judging you. Krash’s music catches both elements.

Jessica Krash: Be Seeing You – VII. Henri Matisse, Lorette with Turban, Yellow Jacket (Jessica Krash, piano; The Sunrise Quartet)

In capturing the Florentine aristocrat Ginevra de Benci, probably at the time of her engagement to Luigi di Bernado Niccolini when she was 16, Leonardo presents us with both a portrait and a metaphor. The juniper bush that frames her head is a symbol of female virtue while also being a play on Ginevra’s name (juniper is ginepro in Italian). On the back of the painting is a painting of a laurel branch, palm frond, and juniper plant with a scroll inscribed Virtutem Forma Decorat (Beauty Adorns Virtue).

Ginevra has flawless skin and fine features under shaded eyelids. She looks at the viewer but keeps her thoughts to herself. Completed when Leonard (at 21) was a little older than his 16-year-old subject, the painting was one of the first in a three-quarter view – earlier portraits were often painted in profile – which gave Ginevra’s clear-eyed glance at the viewer a power not possible before. A writer in the 15th century considered that Leonardo had ‘painted Ginevra Amerigo Benci with such perfection that it seemed to be not a portrait but Ginevra herself’.

Leonardo da Vinci: Ginevra de’ Benci, ca 1474–1478 (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art)

The piano takes the part of Ginevra, living the light-hearted life of a teen, while the strings are her future – marriage and responsibilities.

Jessica Krash: Be Seeing You – VIII. Leonardo da Vinci, Ginevra de’ Benci (Jessica Krash, piano; The Sunrise Quartet)

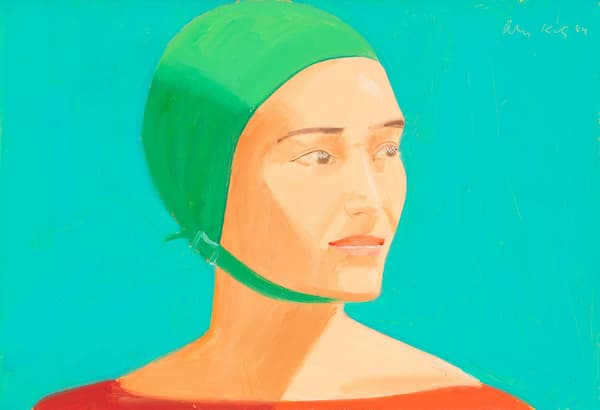

There’s no depth in Alex Katz’s The Green Cap. Its flat planes, plain forms, and striking colours all help to capture a mood, a time, and a moment that might change for each viewer. In his figurative art, Katz stripped down forms to their basics, and in his early works, often tied to the Pop Art Movement, his use of rich colours was distinctive.

The figure in The Green Cap doesn’t engage with the viewer but looks to the side, her eyelashes drawn, covering her eyes, yet not preventing her from taking a keen interest in something to the side, outside our view. The figure might be one of contemplation and self-reflection, but it is always in the viewer’s focus.

Alex Katz: The Green Cap, 1984 (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art)

Krash seems to place us in the figure’s thoughts as though we’ve always been there. There are times of introspection that are then interrupted by hurried rhythms. It’s like one’s thoughts – running here and there, pausing to reflect on something and then running on again.

Jessica Krash: Be Seeing You – IX. Alex Katz, The Green Cap (Jessica Krash, piano; The Sunrise Quartet)

Originally a work in cement and scrap iron left over from a building project, Capricorn, represents the 10th sign of the zodiac. A typical Capricorn figure is of a goat with a fishtail, but Ernst has divided the zodiac’s attributes between two figures: a horned male figure and a mermaid. Ernst always called the work ‘a family portrait’ although his wife, Dorothea Tanning, was doubtful about that.

The original cement and ironwork was rendered in bronze in 1964.

Max Ernst: Capricorn, 1947 (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art)

Krash puts the mermaid into motion, moving her through the water with an ever-building urgency.

Jessica Krash: Be Seeing You – X. Max Ernst, the woman from Capricorn (Jessica Krash, piano; The Sunrise Quartet)

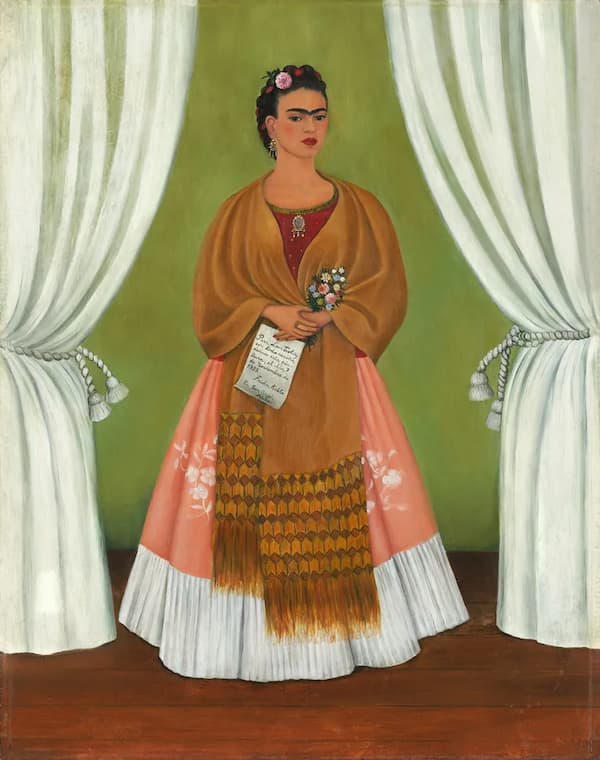

Shortly after his arrival in Mexico in 1937, exiled Russian Revolution leader Leon Trotsky had a brief affair with the Mexican artist Frida Kahlo. In her self-portrait for him, Kahlo presented herself as on a stage, curtain drawn back, wearing traditional Tehuantepec clothing from southwest Mexico. In her hand, she holds a letter of dedication to Trotsky, giving ‘all her love’.

Frida Kahlo: Self-portrait Dedicated to Leon Trotsky, 1937 (Washington, DC: National Museum of Women in the Arts)

Just as defiantly forward as the painting, the music for the work opens with a strong statement in the piano before relaxing into the string melodies.

Jessica Krash: Be Seeing You – XI. Frida Kahlo, Self-portrait Dedicated to Leon Trotsky (Jessica Krash, piano; The Sunrise Quartet)

American artist Helen Turner (1858–1958) found her greatest inspiration in the upstate New York artists’ colony Craigsmoor. Starting in 1906, she spent her summers for the next 35 years there and one of its influences can be seen in the painting The End of My Porch, done in 1914. Craigsmoor was designed as a ‘haven for artists seeking refuge from industrialisation and a return to nature’. Turner rented a cottage there and eventually built her own place, calling it Takusan.

Few of Turner’s paintings at Craigsmoor seem to venture further than her own yard. She often had her focus on her flowers and her garden. Her porch was a frequent setting for paintings between 1912 and 1923.

Much of her style is tied to a broken technique that is not unlike pointillism. There’s a golden glow to the sunshine on the trees behind the artist, shown perched on the porch railing, looking directly at the viewer. Her white summer dress echoes the glittering effect of the sunshine, and her blue coat and sash provide a stable centre while imitating the horizontal element of the porch railing.

Helen Turner: The End of My Porch, 1914

We’re placed on a shady porch on a summer’s day, watching the world go by. Light falls through the trees.

Jessica Krash: Be Seeing You – XII. Helen Turner, On My Porch (Jessica Krash, piano; The Sunrise Quartet)

Suzanne Valadon (1865-1938) painted The Abandoned Doll in 1921; it is one of two paired portraits of Marie Cola with her daughter Gilberte, niece of the artist.

Her childhood doll was discarded on the floor, its pink hair ribbon echoing in her own hair; the girl turned to a mirror to look at herself. On the cusp between childhood and adolescence, the girl sits with an older woman who is drying her with a cloth. Even with her twisted pose and distorted figure, she gives us a promise of the future. Her body has been sexualised but she is still young enough to be passive and does not turn towards the viewer, even with her mirror.

Suzanne Valadon: The Abandoned Doll (Washington, DC: National Museum of Women in the Arts)

The sorrow of abandonment opens the string quintet with thoughts of the past, and yet, there is a quiet optimism in the piano, painting sound images of the world that awaits.

Jessica Krash: Be Seeing You – XIII. Suzanne Valadon, The Abandoned Doll (Jessica Krash, piano; The Sunrise Quartet)

Considered Fragonard’s greatest work, The Swing immediately places us in a rococo world. With its full title, Les hasards heureux de l’escarpolette (The Happy Accidents of The Swing), gives us not only the central figure but also the world around her.

Jean-Honoré Fragonard (1732–1806) studied in Paris with François Boucher, who soon let him create replicas of his paintings. Fragonard’s style has been summarised as being ‘distinguished by remarkable facility, exuberance, and hedonism’. Ignored for decades following his death, his style was picked up by the Impressionists for its use of local colour and its expressive, confident brushstrokes.

The writer Charles Collé reported that the work was commissioned in 1767 by an unnamed gentleman who wished for a painting of his young mistress on a swing pushed by a bishop. The history painter Gabriel-François Doyen, who received the commission, refused it and passed it to Fragonard, Fragonard was in the middle of changing from being a history painter with royal commissions (that were never paid) to being a painter to a small select circle. Paintings like this for Fragonard’s private clients were not exhibited in the annual painting Salon.

The Swing is considered to be one of Fragonard’s greatest paintings. Reading the painting from right to left, a smiling older man (not a bishop) hidden in the shadows propels the swing with ropes, and a small white dog barks at the action. The beauty in the swing flings off her shoe, and as the action lifts her dress, a younger man hidden in the bushes points to her billowing dress. A putti holding its fingers to its lips, Falconet’s sculpture L’amour menaçant (Menacing Love), provides a silent commentary. Fragonard has imbued the often-backward-looking Rococo style with a forceful sensuality.

Jean-Honoré Fragonard: The Swing (London: The Wallace Collection)

Krash’s music places us in a world that is both cute and dangerous. The strings shiver, and the piano’s melody responds to the action. At the end, the swing comes to a rest.

Jessica Krash: Be Seeing You – XIV. Jean-Honore Fragonard, The Swing (Jessica Krash, piano; The Sunrise Quartet)

Krash closes her work with a final Coda.

Jessica Krash: Be Seeing You – XV. Coda (Jessica Krash, piano; The Sunrise Quartet)

In choosing her 14 women, Jessica Krash chose images that depict women as everything from adolescents to goddess-like figures. Experienced women of the world and frothy young mistresses. Women who look at the world through calm eyes and assess it. Since the viewer is on the other side of that gaze, what are these women looking at? Many of them are shown in the fashion of the day – did you go to the museum in your tracksuit again?

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter