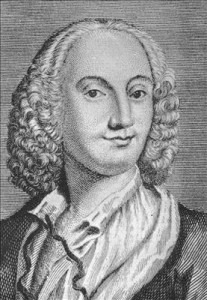

An impresario working in the late 17th century was solely responsible for running all the artistic and business matters of the theater. He rented the house, negotiated and signed contracts with everyone connected with productions. Singers, instrumentalists, technical staff and other support staff for the production had to be engaged as well, promising heavy losses if the opera was a failure. However, in case of success, all profits earned went to the impresario. In addition, impresarios had considerable influence on the artistic side of the production, often choosing the libretto, the composer, and the cast. Amongst all that wheeling and dealing, composers were paid rather modest sums for composing the music. You can see the conundrum faced by aspiring composers like Antonio Vivaldi. Although his music significantly contributed to the success of a production, all the money went to the impresario! It is hardly surprising that Vivaldi, blessed with great organizational skills, devoted much of his energy to being an impresario. And his early focus fell on the Venetian Carnival season, a period of frenetic activity when all theaters were open and putting on daily performances.

An impresario working in the late 17th century was solely responsible for running all the artistic and business matters of the theater. He rented the house, negotiated and signed contracts with everyone connected with productions. Singers, instrumentalists, technical staff and other support staff for the production had to be engaged as well, promising heavy losses if the opera was a failure. However, in case of success, all profits earned went to the impresario. In addition, impresarios had considerable influence on the artistic side of the production, often choosing the libretto, the composer, and the cast. Amongst all that wheeling and dealing, composers were paid rather modest sums for composing the music. You can see the conundrum faced by aspiring composers like Antonio Vivaldi. Although his music significantly contributed to the success of a production, all the money went to the impresario! It is hardly surprising that Vivaldi, blessed with great organizational skills, devoted much of his energy to being an impresario. And his early focus fell on the Venetian Carnival season, a period of frenetic activity when all theaters were open and putting on daily performances.

Initially, Vivaldi signed appointment papers to manage the Venetian Carnival seasons of 1714 and 1715, and he also became the impresario at the “Sant’Angelo” theater in 1716.

Initially, Vivaldi signed appointment papers to manage the Venetian Carnival seasons of 1714 and 1715, and he also became the impresario at the “Sant’Angelo” theater in 1716.

Vivaldi got his feet wet with a highly successful production of Orlando furioso by Giovanni Alberto Ristori, and an opera by Michel Angelo Gasparini. Empowered by his initial success, Vivaldi set to work and produced his first opera specifically written for Venice. Unfortunately, Vivaldi’s first setting of Ariosto’s epic poem Orlando finto pazzo came at an inopportune time, and it closed after a couple of weeks. However, Vivaldi still raked in the profits as his opera was replaced by the revival of Ristori’s popular setting on the same topic. During the 1715 season Vivaldi presented the pasticcio Nerone fatto Cesare. The opera contained music by seven different composers, including an aria by Vivaldi. A contemporary critic wrote on 19 February 1715, “In the evening I saw, at the small St. Angelo opera house, an opera composed entirely by and produced by Vivaldi. I did not like it, neither for the subject matter nor the decor nor, especially, the costumes… in short, it was a quite absurd mishmash of things that did not belong together; and Vivaldi only played a short violin solo.”

Antonio Vivaldi: Arsilda, regina di Ponto, (RV 700), Act I: Aria: La tiranna avversa sorte

Va per selve e sol pien d’ira

Va superbo quel vassallo

Vivaldi had plans to present an original opera to Venetian audiences in 1715. However, his Arsilda regina di Ponto fell afoul of government censors. The problem was a racy plot that saw the main character Arsilda falling in love with another woman, who in turn pretended to be a man! After a bit of wining and dining, Vivaldi got the censors to accept the opera the following year. With his reputation as an impresario and composer firmly established, Vivaldi added the San Moisè theatre to his performance venues, and when he left Venice to take up the post of court music director in Mantua, he immediately composed several operas and managed the opera houses. In fact, over a period of roughly 25 years, Vivaldi was responsible for composing 50 operas and had his hands in the production of as many as 94. His activities as an impresario, however, were fraught with significant difficulties that caused him a good deal of frustration. His most outspoken critic was the magistrate and amateur musician Benedetto Marcello, who wrote the pamphlet Il teatro alla moda. Satirizing Vivaldi’s style of dedications, Marcello declared, “he hereby kissed with great respect, the fleas on the paws of Your Excellency’s dog.” To be sure, virtually every aspect of “opera seria” and its environment was mercilessly criticized. This included the “artificiality of plots, the stereotypical format of the music, the extravagant scenery and machinery, the inability of composers and poets, the vulgarity of singers, and the avidity of impresarios.” However, as you can clearly see in the drawing on the cover, Marcello’s primary target was Vivaldi. How else can we explain the little angle, wearing a priest’s hat and playing the violin on the left end of the boat! Regardless, Vivaldi made a fortune as a composer and impresario, but sadly his success did not last. During the final years of his life he was forced to beg for money from his aristocratic friends.

Antonio Vivaldi: La costanza trionfante (RV 706), excerpts

You May Also Like

- Movers and Shakers of Music World

Emanuel Schikaneder (1751-1812): The Original Papageno He has been called “one of the most talented theatre men of his era,” and we primarily know him for writing the libretto of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s opera - Movers and Shakers of Music World

Paul Sacher: Plutocrat and Patron Without the extraordinary generosity of legendary conductor, patron, and impresario Paul Sacher, a myriad of masterworks by twentieth-century composers would simply not exist. - Movers and Shakers of Music World

Sir Rudolf Bing The opera stars of the1950s to 1970s have become household names: Maria Callas, Renata Tebaldi, Richard Tucker, Robert Merrill, Joan Sutherland and Franco Corelli. - Movers and Shakers of Music World

Johann Peter Salomon: “He brought Haydn to England” King Edward the Confessor started to rebuild St. Peter’s Abbey—today known as Westminster Abbey—between 1042 and 1052 to provide himself with a royal burial church.

More Anecdotes

- Bach Babies in Music

Regina Susanna Bach (1742-1809) Learn about Bach's youngest surviving child - Bach Babies in Music

Johanna Carolina Bach (1737-81) Discover how family and crisis intersected in Bach's world - Bach Babies in Music

Johann Christian Bach (1735-1782) From Soho to the royal court: Johann Christian Bach's London success story - A Tour of Boston, 1924

Vernon Duke’s Homage to Boston Listen to pianist Scott Dunn bring this musical postcard to life