The archduchess of Austria, Marie Antonia Josepha Johanna arrived in France at the age of 14. She became dauphine of France, under the name Marie Antoinette, when she married Louis-Auguste in May 1770. Four years later Louis-Auguste ascended the throne as Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette became queen.

Jean-Baptiste André Gautier-Dagoty: Marie Antoinette playing the harp at the French Court

Marie Antoinette had always been artistically inclined, as she was a competent singer, dancer—she received ballet lessons from the French master Jean-Georges Noverre—and instrumentalist. In fact, music always played a prominent role in her life. As soon as she arrived in Paris, Jeanne-Louise-Henriette Campan—an educator and writer—was assigned her Lady’s maid. Madame Campan remembered, “The Dauphine, who assuredly preferred music to intellectual effort, found the wherewithal, in spite of receptions, hunting parties and theatrical performances, to reserve an appreciable portion of her time for it every day, and in short music was her principal occupation during the first years of her marriage.”

The royal instrument of choice was the harp, which she took up with a burning passion. We really have no idea how well Marie Antoinette played the instrument, but her daily music studies did include harp lessons. Said harp lessons were provided by the German harpist Philipp Joseph Hinner (1755-1784).

Joseph Philipp Hinner: 3 Harp Duets, Op. 8, No. 1 (Alchimia Duo)

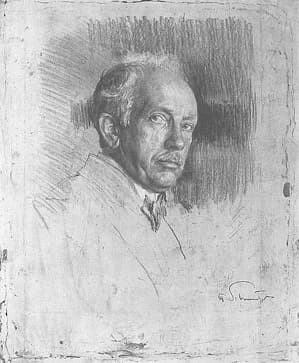

Philipp Joseph Hinner

Young Hinner had spent some time in French-Guyana, and after the death of his parents was brought to Paris. Exceptionally talented, Hinner soon performed at the “Concert spiritual,” and was appointed harpist at the “Chapelle Royale.” He took Marie Antoinette under his wing in 1774, and he officially carried the title “maître de harpe,“ and “harpiste de la musique du roi et de la reine.“ It is said that Hinner and Marie Antoinette gave frequent concerts at the courts, and a good many of his harp duets seem to have been written for such occasions. Marie Antoinette did much to promote the operas by Christoph Willibald Gluck (1714-1787), who in turn became her official music teacher. He instructed her in the art of playing the harpsichord, the flute, and helped her to develop into a fine singer. He might even have awakened her interest in composition, as Marie Antoinette is said to have authored a number of delightful songs.

Marie Antoinette: “C’est mon ami” (Isabelle Poulenard, soprano; Sandrine Chatron, harp)

Johann Baptist Wendling

Marie Antoinette’s love for music and the arts was well publicized across Europe. As such, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart fancied his chances of securing a court appointment as “writing opera is now my one burning ambition.” With his compatriot Marie Antoinette securely installed as Queen of France, Mozart headed towards Paris. On his way, he did stop in Mannheim during the winter of 1777/78. Once arrived, he made the acquaintance of Elisabeth Augusta Wendling, daughter of the Mannheim flautist Johann Baptist Wendling. Augusta, commonly known as “Gustl” was an able soprano who had turned down a marriage proposal from Johann Christian Bach, a fact that provided much amusement to the young Mozart. Soon after his arrival in Mannheim, he received two French texts from “Gustl” and quickly set them to music. Mozart reports, “at the Wendling household it is sung every day for they are absolutely crazy about it.” Although the accompaniment was destined to be provided by piano accompaniment, it works remarkably well when played by the harp. By setting a French text to a possible harp accompaniment, Mozart appears to have knowingly composed a musical calling card for his upcoming visit to Paris.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: “Oiseaux, si tous les ans,” K. 307 (Isabelle Poulenard, soprano; Sandrine Chatron, harp)

Marie Antoinette’s harp

Music at the court of Marie Antoinette was not merely social pleasure. It also communicated a life of privilege, refinement and wealth. The harp, as has been suggested in recent scholarship, “was not only a musical instrument but a social prop that was used to highlight the body…The harp proved to be a powerful instrument of seduction and a sexual stimulant for players and spectators.” As has been written, “a young woman hugs her thighs suggestively around the harp, even revealing a popped ankle… Although confined and immobilized by the bulk of the harp, the young woman successfully adjusts her body to communicate sensuality and elegance.” For Marie Antoinette’s birthday, Jean-Louis Naderman presented the Queen with a beautiful instrument decorated with “flower and hand-painted depictions of the patroness of artists.” Magnificently decorated with relief carving, lavishly gilded and hand painted, harps were prized as “objets d’art” and frequently commanded a special room.

Jean-Baptiste Krumpholtz: Sonata in F Major for flute and harp (Robert Aitken, flute; Erica Goodman, harp)

Sébastien Érard

When Marie Antoinette arrived in Paris in 1770, the harp was already a relatively widespread instrument in Paris. However, her unwavering passion for the instrument was partially responsible for inspiring a veritable harp craze. Also contributing to the popularity of the instruments were important contributions to the development of the single-action harp by Sébastien Érard (1752-1831). He refined the older generation of instruments crafted by Georg Hochbrucker, a member of a family of Bavarian instrument maker. Apparently, Hochbrucker had the initial idea of adding pedals to shorten the strings and thus alter the notes chromatically. Sébastien Érard, initially a fortepiano builder, took up this idea and consulted with the virtuoso harpist Jean-Baptiste Krumpholtz (1742-90). He is considered the inventor of the “opening shutters, which made it possible not only to prolong and enlarge the sonority of the instrument, but also to produce tremolo.” Krumpholtz hailed from Bohemia, and he is still considered the foremost classical composer for the harp. He studied with Georg Christoph Wagenseil and Joseph Haydn before moving to Paris in 1777. He married Marguerite Gilbert, the daughter of a harp maker and busily appeared at the Concert Spirituel.

Jean-David Hermann: Harp Concerto No. 1 in F Major, Op. 9 (Xavier de Maistre, harp; Les Arts Florissants Ensemble; William Christie, cond.)

‘Grecian Harp’ by Sébastien Érard

Krumpholtz constantly pushed the boundaries of his instrument and exploited its expressive potential to the fullest. Since the single-action mechanism did not permit ease of execution, he pioneered the use of enharmonic techniques to remedy this shortcoming. He conceived the “pédale de renforcement,” operating shutters to reinforce the sound, and the mute pedal “pédale de sourdine.” This pedal operated a damper situated on the bridge between the strings, and Krumpholz is also “considered the inventor of the pedal glissando.” Following his first appearance at the Concert Spirituel in 1785, Marie Antoinette immediately engaged Jean-David Hermann (1760-1846) as her fortepiano teacher. Very few works of Hermann seem to have survived, among them, however, three concertos for harp. Interestingly, his third harp concerto is dedicated to Madame Élisabeth, Louis XVI’s younger sister. She was also a harpist and really did not get along at all with her sister-in-law Marie Antoinette.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Concerto for Flute and Harp, K. 299

Hermann’s harp concertos possess a special significance, as they “were among the first harp concertos written by a composer who was not himself a harpist. The same is of course true of Mozart’s delightful Concerto for Flute and Harp, composed in the spring of 1778 in Paris. Arriving from Mannheim, Mozart found Marie Antoinette indisposed and unable to entertain him. Mozart took on a host of private students, and hoping to obtain a lucrative musical post in Paris, composed on commission. In April 1778 he was engaged to give composition lessons to Marie-Louise-Philippine Bonnières, youngest daughter of the Duke of Guînes. His young charge was a capable harpist, and the duke an excellent flutist. As such, the duke commissioned Mozart to compose a concerto that he could perform with his daughter. It is said that the duke never paid for the commission, and that it might never have been performed. Mozart, it has been suggested, had rather ambivalent feelings towards the harp. And in fact, he might simply have considered the harp as kind of plucked piano, as the concerto lacks the glissandi and broadly dramatic arpeggios we think of as idiomatic harp gestures.

Joseph Bologne Chevalier de Saint-Georges: Sonata for Flute and Harp in E-flat Major (Amelie Michel, flute; Sandrine Chatron, harp)

Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges

Known in contemporary circles as the “Black Mozart,” the Chevalier de Saint-Georges (1745-1799) created a sensation by performing as a violin soloist for François-Joseph Gossec’s “Le Concert des Amateurs.” He was, according to newspaper reports “appreciated not as much for his compositions as for his performances, enrapturing especially the feminine members of his audience.” Nevertheless, Saint-Georges was a capable composer, taking his inspiration from the early string quartets by Haydn. Besides several sets of string quartets, he also wrote 3 forte-piano and violin sonatas and 6 violin duets. Saint-Georges definitely had his finger on the pulse of his time as he also authored a sonata for harp and flute. The violinist and composer Jean-Guillain Cardon, meanwhile, was appointed court violinist at Versailles. His son Jean-Baptiste Cardon (1760-1803) took a distinct liking to the harp, and at the tender age of fifteen entered into the services of Maria Theresa of Savoy, the princess of Sardinia, wife to the Count of Artois who later became King of France as Charles X. In 1784, Cardon published his textbook “L’Art de jouer de la harpe” a method that significantly expanded the technique of the instrument and contributed to a previously unknown virtuosity of harp playing. Cardon was a darling of concerto audiences, but when the French Revolution got started in earnest, he accepted an appointment by Tsarina Catherine II of Russia. As for Marie Antoinette, And we all know what happened to Marie Antoinette.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Jean-Baptiste Cardon: Harp Sonata in E-flat Major, Op. 7, No. 1 (Anna Sikorzak-Olek, harp; Konstanty Andrzej Kulka, violin)