“Mahler’s total symphonic work, as the final, highest product of the Romantic worldview, is at once guarantor and foundation of a new idealism.”

~ Paul Bekker

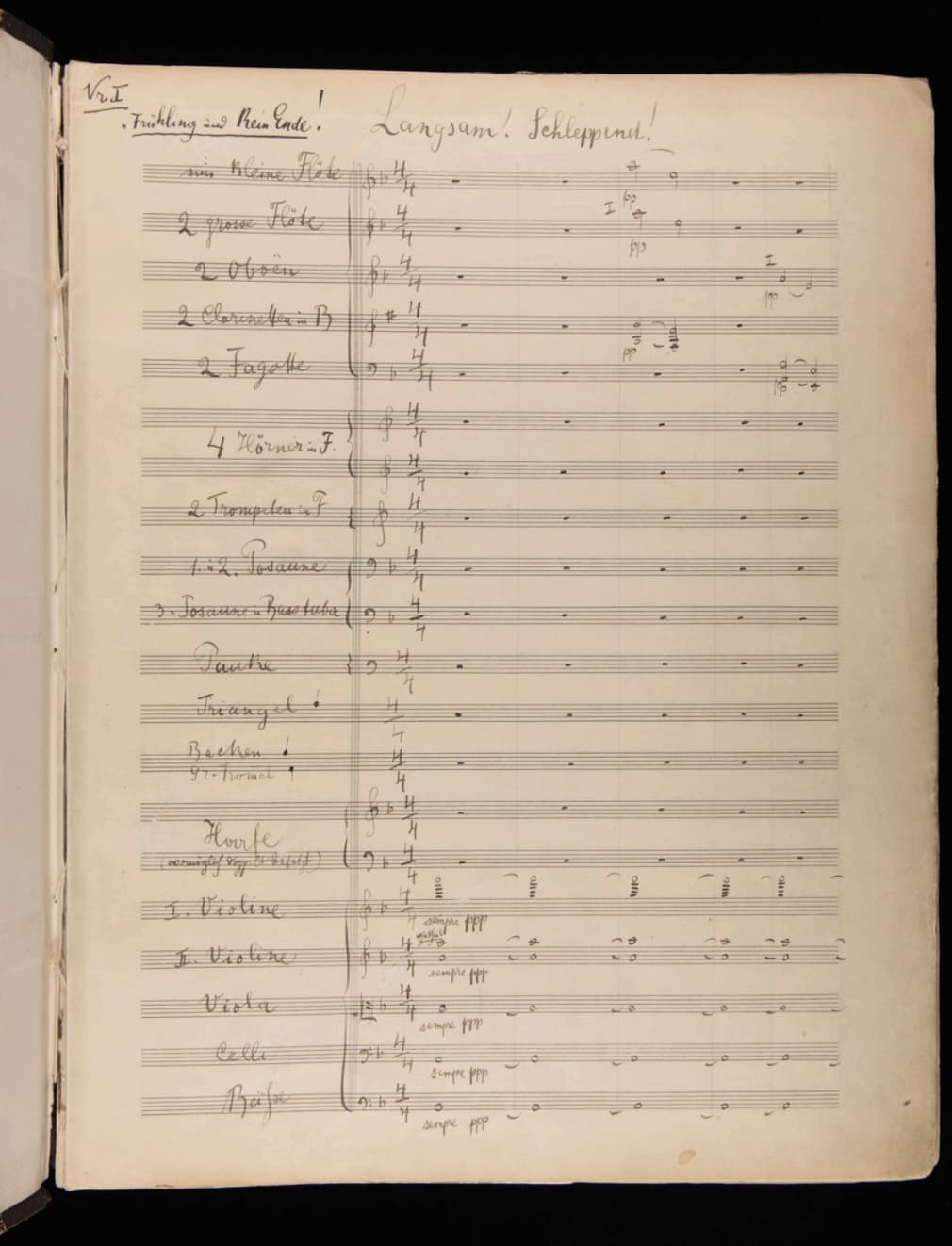

Courtesy of the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University

Vienna, at the turn of the 19th century, was in its cultural prime, with legends in the likes of Freud, Nietzsche and the Viennese art nouveau school, called Secession. Composers such as Richard Strauss, Arnold Schoenberg, as well as Richard Wagner were part of cutting edge Vienna, with musical works connected with their contemporary thought and art styles. Gustav Mahler was an anomaly in this regard: he was inclined to the early Romantics of the 1800s, engaging heavily with nature and a rediscovery of folk soundscapes. This affinity with natural landscapes seemed to nurture within Mahler a new geographical awareness of music; among the many 19th-century Tondichter (tone poets), there was none more effective with orchestral colours than Mahler.

***

The Opening: Cosmic Proportions of Nature

Mahler’s First Symphony opens with seven octaves of As, with strings entirely in natural harmonics – this sonic evocation was the emblem of the cosmic. Mahler is well-known today as a proponent of Weltanschauungmusik (world-view music), as indicated in his oft-quoted aphorism: “A symphony must be like the world.” The sheer range and the elusive colour of these figures laid out Mahler’s intentions from the start.

Utterances from woodwinds follow, almost all of which are the simple interval of a fourth. Even the clarinet’s cuckoo call that breaks the silence is built from that fourth. Gradually one fourth gets stacked upon another in a fragile attempt to build a theme. Presenting a main theme through genesis was not an alien concept: Beethoven’s Pastorale symphony has an opening that withers away shyly and incompletely on the first instance and then, after a series of developments, grows into a fully-fledged, fortissimo theme. Mahler’s theme is much more expansive, yet he plays with an intervallic cell (the smallest melodic unit possible) and generates a variety of characters through it. While his predecessors often made subtle musical associations to nature, Mahler did not shy away from obvious natural devices – the cuckoo, the bugle calls, the nightingale (in the finale) – instead of forcing them into a wider melodic context, he contented with presenting them as their own organic units and allowing them “full interpretive space” (quoting Mahler).

The start of the exposition is a magical moment when that cuckoo finally sounds and reveals itself as the opening to one of Mahler’s Songs of a Wayfarer. It’s as if the chain of fourths had traversed a long barren space between the glacial string figures and had finally found its tonic in a stroke of springtime exuberance.

***

The Opening: “As if from afar”

In the vastness of our modern-day repertoire, the ‘offstage trumpet calls’ may be rendered as cliché or even, in the words of 20th-century critics, as ‘acts of excess’. Nonetheless, in Mahler’s time, these features were not only rare but also exclusively to operatic/theatrical works; having an instrumental sound ‘from afar’ in the concert hall seemed antithetical to the ‘sacred nature’ of absolute music.

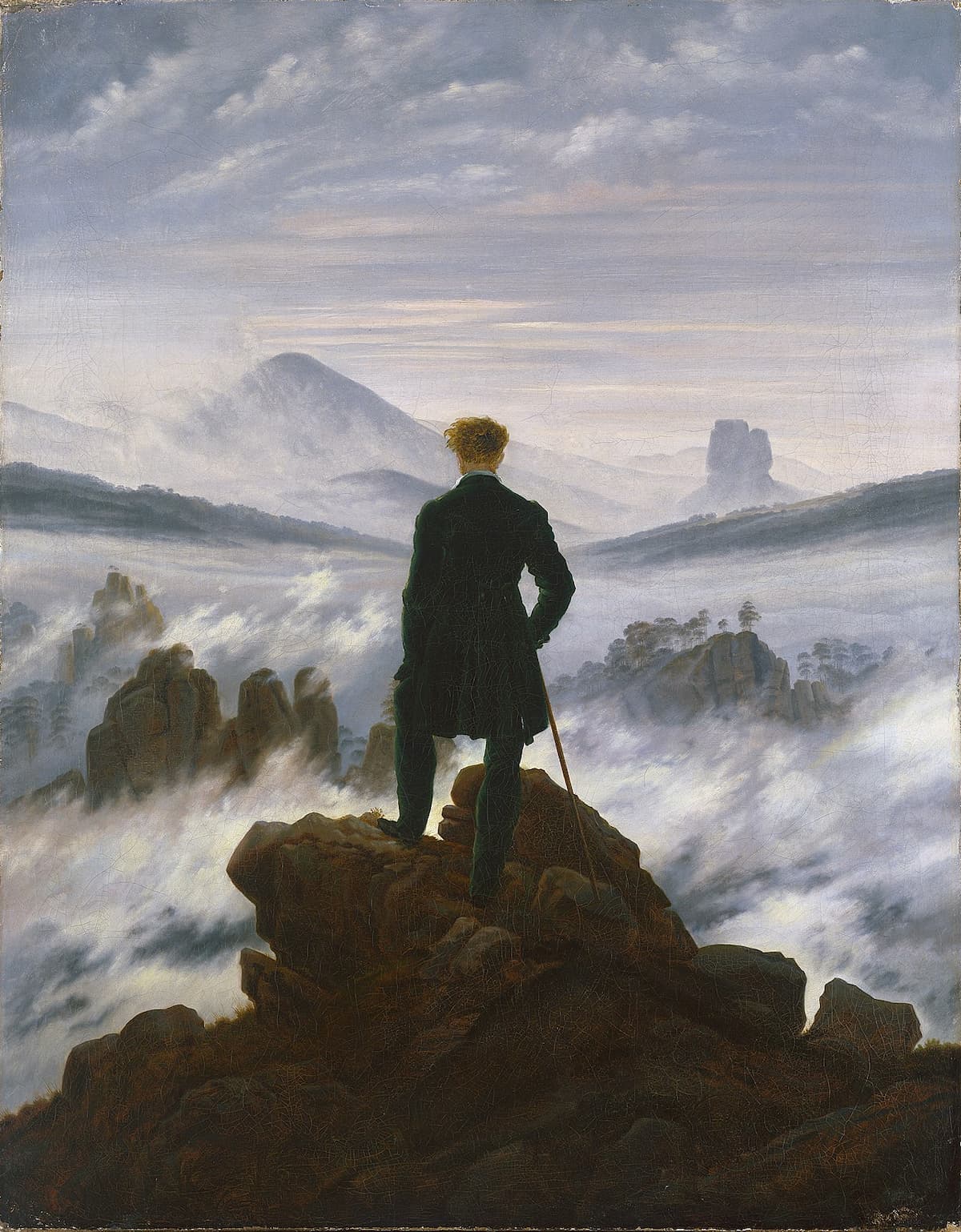

The Wanderer over the Sea of Fog (1818), by Caspar David Friedrich. This hallmark Romantic-era painting encapsulates the impulse to nature, the idea of a hero aspiring to the distant and the common trope of the Wanderer.

The music philosopher Theodor Adorno described Mahler’s symphonies as “opera assoluta” – operas in the genre of absolute music. At a time when absolute and program music were in an antithetical relationship, Mahler was an agent who forged a link between the two spheres. Many years of work in opera houses had added a theatrical quality to his symphonic impulses, and the act of flexibly displacing instruments throughout a hall was an evident link to the flexible geography of the stage. One can trace Mahler’s vocabulary of offstage “bugle calls” as influenced by Beethoven’s Fidelio – in particular, the trumpet call that sounds from afar, such as Leonore comes to the rescue of the politically-imprisoned Florestan. Mahler delights in the impression of distance – often noting “wie aus der Ferne / in weiter Entfernung” (as if from afar / in the distance) in his music. The idea of distance was a hallmark of early Romantic music and poetry: Beethoven’s song cycle An die ferne Geliebte (To the Distant Beloved) is regarded as the trailblazer of musical romanticism. Mahler’s symphonies, instead, now go beyond the theme or idea of distance and integrate them into their own sound palette.

(An interesting factoid: when asked about his approach to orchestrating soft, subdued sounds, Mahler said he scored them for instruments that can only get the notes with effort and pressure—almost having to force or exceed themselves!)

***

The Third Movement: The Original Soundwalk

The opening gesture of the movement quite the stroke of mystery: it presents the nursery tune Frère Jacques in a pianissimo minor-key canon spread over two minutes. There is a noticeable element of irony here – the canon in western classical music is often considered a display of ‘intelligence’ – yet without a single hint of harmonic change, the music simply becomes a bed of sound: perhaps that soundscape was what Mahler was aiming for?

As the music continues, abrupt interjections are signified by a pair of piercing E-flat clarinets and the steadily vamping percussion rhythm of a “Turkish march”. These active interjections disrupt the sombreness of the funeral march, seeming almost out of place. That distinct sound world, however, evokes Jewish klezmer music, which Mahler would presumably have assimilated from his childhood. In an interview in 1911, Mahler emphasises the significance of music that is “mentally digested” from one’s childhood upbringing – in a sense that folk songs or nursery tunes could transform into the most vivid, masterful compositions (in fact, this could equally be applied to the previous Frère Jacques theme).

With all these ever-varying elements laid one upon another, it almost seems like there is an underlying narrative in play. As a modern scholar, I cannot help but compare this to the process of soundwalking. The soundwalk as a musical concept is quite a recent, postmodern device – it was only proposed in the 70s, amidst a time when musical circles started debunking ‘music creation/reception’ as something beyond the score and its ‘dots’ and seeking a sonic immersion into a particular environment. Albeit a century prior, I would interpret this third movement as equipped with the same ethics as the modern soundwalk – they both seek to totally and aurally experience the aesthetic of a time and place. I can envision Mahler harking back to a childhood setting, delineating his movement through a particular landscape, and narrating it through notes rather than words. I can see the abrupt interpolations of klezmer themes as streetbands from afar getting within earshot and fading out (in diminuendo/ritardando) as Mahler walks on thither. Mahler’s product of soundwalking does, altogether, provide us with what may be a canvas from his early life – often left behind him as he entered the school of Austro-German music.

***

The First Symphony is a lofty milestone for any budding composer. Beethoven’s First flipped the classical symphonic traditions on its back through wit, irony and his own temperament; Brahms’ First (in the long shadow of Beethoven) expands massively on the traditional sonata form, with associations with Austro-German cultural heritage and the master Beethoven himself. Mahler’s First opens up an entirely new dimension of the ‘symphony’, enhancing it from a linear trajectory through time into one that covers both time and space. In a genre monopolised by absolute music, Mahler’s symphonies add many distinct touches of theatricality, which paved the way for the “symphonic-tone poetry” for Richard Strauss and beyond. Despite being a “cultural outsider” of the time (being Bohemian in nationality and Jewish in race), Mahler’s symphony has, in hindsight, successfully ‘written’ him into the Austro-Germanic canon.

On 9 August (Fri), the Hong Kong Youth Philharmonia will perform Mahler’s First Symphony, conducted by Isaac Chan. Also on the programme is Grieg’s Piano Concerto, featuring the wonderful young pianist KaJeng Wong, and a world premiere Dreaming of Butterfly by Nok-Him Chan, conducted by Henry So. Please click the link here for tickets.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Isaac Chan is currently reading Music at the University of Cambridge (Clare College). Originally a French horn player, he now focuses his time avidly on orchestral conducting, and enjoys playing collaborative piano. As of 2024, he is Conducting Scholar at the University of Cambridge, where he will conduct the university Symphony Orchestra and Wind Orchestra. Formerly a graduate of Chetham’s School of Music sixth form, he founded and conducted the Chetham’s Camerata and Operetta, where he put on multiple projects including his operatic debut of Hansel and Gretel in 2022. He currently studies conducting with Sian Edwards at the Royal Academy of Music.

Since being at Cambridge, Isaac has thoroughly enjoyed extensive academic work on music, as well as collaborated with multiple academics on lecture-performance events. While a music analyst at heart, he counts 19th-century German instrumental and vocal music, as well as Italian-French opera studies as his chief interests. He was recently awarded the Donald Wort Prize for coming top of the class in his first year.