What would you say if I told you that the entire musical history of Vienna would be extremely different, if not for the little-known, strong-willed daughter of an Austrian pub owner?

Today we’re looking at the life and times of Maria Anna Streim, later known as Maria Anna Strauss, the matriarch of the Strauss dynasty.

If Johann Strauss II is the Waltz King, Anna Strauss is surely the dance’s queen mother. Today we’re looking at her extraordinary life story.

Maria Anna Strauss

Meeting and Marrying Johann Strauss I

Maria Anna Streim was born on 30 August 1801. Her father was a pub-owner in suburban Vienna.

In early 1825, when she was 24, she got pregnant by 20-year-old violinist and composer Johann Strauss. He was talented and ambitious, and had just expanded his dance band from a quartet to a string orchestra.

Johann Strauss I: Kettenbrücke,Walzer Op.4

As soon as Maria Anna realised she was pregnant, the couple married in July 1825. She gave birth to Johann Strauss II that October.

During their marriage, she had five other children: Josef in 1827, Anna in 1829, Therese in 1831, Ferdinand in 1824 (tragically, he died the same year), and Eduard in 1835.

Johann I’s Controlling Nature

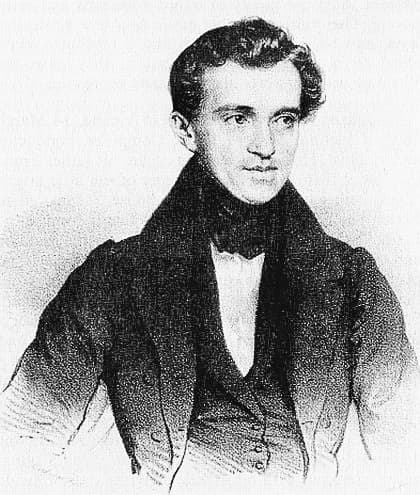

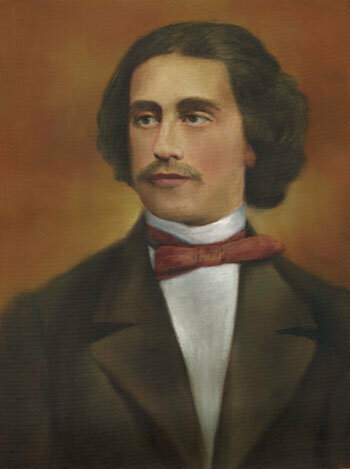

Johann Strauss I, 1835

During the first flush of his success, Johann I moved his family into an apartment in the center of Vienna.

His wife and children lived in one part of the home, while in the other, he kept his own rooms, including a couple of rehearsal spaces for his orchestra.

These at-home rehearsals exposed the Strauss children to the business from a very early age, sparking a love of music in all of them.

However, Johann I forbade his musically talented sons from pursuing careers in the field. Instead, he created detailed life plans for them, deciding that Johann II would go into banking, Josef would go into the military, and Eduard would go into diplomacy.

Although he believed he was entitled to micromanage his children, he was frequently absent from their lives, embarking on multiple tours that took him away from Vienna for weeks or months at a time.

Tensions rose, and it wasn’t long before Anna began to feel betrayed and abandoned.

Johann I Takes a Mistress

These frequent absences provided openings for Johann I to be unfaithful to his wife.

In 1834, he took a 20-year-old mistress named Emilie Trampusch. To help support her, he set her up with a millinery shop.

Apparently, Anna was willing to tolerate her husband’s dalliances, but setting up a mistress in another home – in Vienna, no less! – was a bridge too far.

Two months after giving birth to Eduard, Anna found out that her husband was having children with Emilie Trampusch…and publicly acknowledging their paternity. The couple would even name their eldest son Johann.

Anna was humiliated and enraged. The marriage was over.

Johann II Secretly Studies Music

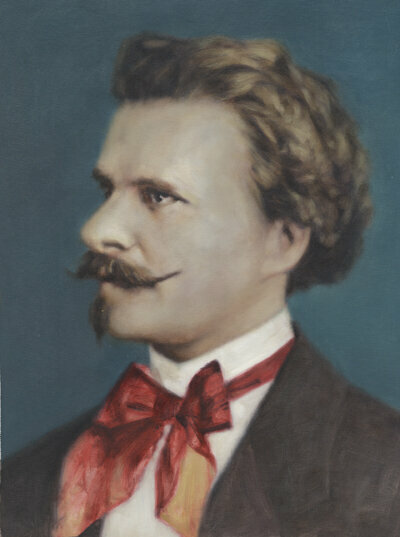

Johann Strauss II, 1888

Meanwhile, Johann II badly wanted to study music, despite his father’s having forbidden it.

Anna, no doubt, motivated in part by her own deteriorating relationship with her husband, arranged for her musical son to study with Franz Amon, concertmaster of the Strauss orchestra.

One day, Johann I overheard the boy playing violin. He stormed into the room and whipped him. But neither mother nor son let the violence stop his studies. Music was turning into Anna and Johann II’s escape plan.

Johann II began studying counterpoint and harmony with a professor and organist named Joseph Drechsler, as well as violin with Anton Kollmann, the ballet répétiteur (accompanist) for the Vienna Court Opera.

A particularly fateful day for the family came on 31 July 1844, when mother and eighteen-year-old son launched a joint attack on Johann I.

She submitted a petition for divorce, citing her husband’s infidelity.

Meanwhile, Johann II submitted an application to the city council, seeking to work as a musician.

Mother and Son Try to Take Down Johann I

The Strauss brothers

These two actions were connected. They telegraphed to the community that Anna and Johann II were willing to team up and compete with Johann I to support themselves financially, since Johann I was no longer interested in helping them.

The teenaged Johann II assembled a dance band like his father’s, hiring musicians from a local tavern and whipping them into performing shape himself.

Johann I was furious. He let venues across Vienna know what his wife and son were doing, and many, not wanting to upset Johann I, refused to hire Johann II.

However, Johann II did manage to secure a booking at Dommayer’s Casino in suburban Vienna in October 1844.

Unfortunately for Johann I, his son’s appearance there was an unqualified triumph. A critic from Der Wanderer wrote, “Strauss’s name will be worthily continued in his son; children and children’s children can look forward to the future, and three-quarter time will find a strong footing in him.”

While there, in gratitude for his mother’s support, he performed a waltz that he had originally titled “The Heart of a Mother” (it would later be renamed to “Seekers of Favor”, on Anna Maria’s advice).

Rivalry and Revolution

Over the next few years, father and son became bitter rivals (although Johann II was always happy to play his father’s music, since audiences loved it).

In 1848, a series of revolutions broke out across Europe, including in the Austrian Empire.

Johann I had once been named to the prestigious court position of KK Hofballmusikdirektor, so he sided with the aristocrats and royal family. In fact, he wrote the famous Radetzky March in praise of Hapsburg field marshal Joseph Radetzky von Radetz.

Orchestra Filarmonică din Viena – Marșul Radetzky Op. 228

But Johann II sided with the revolutionaries, going so far as to perform La Marseillaise, the veritable theme song of the French Revolution. After the Austrian revolutionaries were suppressed, Johann II was arrested, but ultimately acquitted.

Johann I’s Death

Maria Anna Strauss

This new wrinkle in the adversarial dynamic between father and son didn’t have much time to play out.

Tragedy struck in the autumn of 1849, when Johann I came down with a case of scarlet fever that he’d caught from one of his illegitimate children.

Taking the advice of his mother, 23-year-old Johann II moved quickly to merge his orchestra with his father’s.

He also set to work composing waltzes named after the new emperor, Franz Josef I, who had ascended to power after the 1848 revolutionary movement. Now that his father was dead, his dream was to be named KK Hofballmusikdirektor, too…but unfortunately for Johann II, his history with the revolutionaries would prove to be an obstacle for years.

His mother helped to choreograph his career during this pivotal time. She understood that in an era before stringent copyright protections, it was a financial imperative to establish Johann II’s status as the true heir and successor to Johann I.

To that end, she went to work defaming Emilie Trampusch and the Trampusch-Strauss boys.

She also ended up overseeing the younger Strauss brothers’ entrance into the family firm (eventually named Strauss Entertainment Music).

Bringing Josef Strauss Into the Fold

Josef Strauss

Johann II’s brother Josef was an impressively talented Renaissance man. He originally trained to become an engineer, and even invented a street cleaning machine.

In 1853, when Johann II had a weeks-long nervous breakdown due to overwork, Anna pushed 26-year-old Josef Strauss to step up to lead the orchestra, despite the fact that he hadn’t studied much music at all, besides what he’d learned via osmosis.

He also published his first waltz, “The First and the Last”, in 1853. Eventually, he would write 283 works with opus members.

Music of the Spheres, by Josef Strauss

Like his brother and father, he was received rapturously, although his popularity would never eclipse Johann II’s. Johann II once remarked, “Pepi [Josef’s nickname] is the more gifted of us two; I am merely the more popular.”

Josef was sickly through much of his adult life, complaining of frequent headaches and dizziness. He fell off a conducting podium while touring Warsaw in 1870, and died that July. He was just 42 years old.

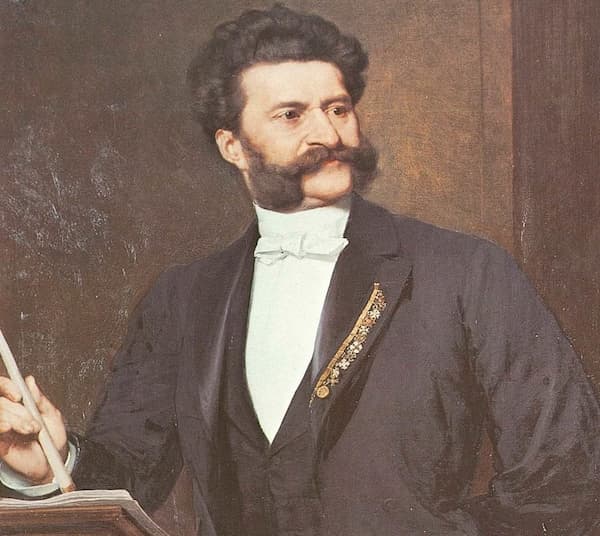

Eduard Strauss Takes the Baton

Eduard Strauss

The youngest Strauss brother, Eduard, was also enlisted into the family business. He was never as popular as Johann II or Josef, but he did carve out a niche for himself writing polkas.

Later in life, after Josef had died and Johann II had shifted his attention to writing operetta, Eduard took over the family orchestra.

Brakes Off, Quick Polka by Eduard Strauss

He had a famous rivalry with another conductor named Karl Michael Ziehrer, who made the infuriating decision to name his orchestra the Formerly Eduard Strauss Orchestra. Legal drama ensued.

The family spent down the money Eduard had helped to earn, without Eduard seeing a proportional share of the benefits. By the turn of the century, he became disillusioned and decided to step away from the business.

He disbanded the orchestra after an international tour in 1901, and wrote a memoir about his family in 1906. He died in 1916.

The Strauss Family’s Golden Age, and a New Wife

The firm’s most successful years were between 1863 and 1870. Many of Johann II’s most famous compositions were published during this period.

The Beautiful Blue Danube – Francisco Navarro Lara – Wiener KammerOrchester

Anna’s management of the family business enabled Johann II in particular to concentrate on performing and composing, without having to worry as much about day-to-day management issues.

This period of productivity also overlapped with the introduction of another woman to the firm. In 1862, Johann II married the singer Henrietta “Jetty” Treffz. She, like Anna, had definite ideas about how Johann II’s career should evolve. Not surprisingly, given her background, she envisioned him writing more operetta.

Jerry Hadley – Die Fledermaus: Act I Scene, Duet & Trio Rosalinde – Alfred – Frank

At first the family was leery about Jetty and her colorful romantic past. But they soon came to respect the value she added to the business.

Josef wrote in 1869 that Jetty was “indispensable in the home. She writes up all accounts, copies out orchestral parts and sees to everything in the kitchen with such efficiency and kindness that it is admirable.”

The Death of the Strausses

In February 1870, Anna died. She was sixty-eight years old. Her son Josef died just a few months later. The golden age of the Strauss dynasty was over.

Johann II responded to these losses by shifting from performing to following Jetty’s advice and composing operettas. Meanwhile, Eduard began his run conducting the family orchestra.

Anna Maria Strauss has long been an unsung hero of the Strauss family, who has been almost completely forgotten today.

But the history is clear: without her savvy and determination, her son would not have become a cultural icon, and the musical legacy of Vienna would be much poorer today.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter