Franz Schubert’s final chamber work, the String Quintet in C Major (D. 956) is regarded as one of the greatest compositions in all of chamber music. The “sublime” second movement has long been viewed as the essence of coming to terms with the end of life. The famous novelist Thomas Mann wanted it played on his deathbed, as did pianist Arthur Rubinstein, and Benjamin Britten considered “Schubert’s final year as the most miraculous year in the history of music.”

Franz Schubert, c. 1827

Completed just two months before the composer’s death in 1828, D. 956 is frequently described as a work in the “late style.” But what does that actually mean? Schubert was only in his late twenties, and he was certainly an experienced, calm, and confident composer. Did Schubert expect to die, and did this knowledge inspire a flowering of a late compositional style? As a scholar wrote, “Is it even viable to speak of late style in a composer who died so young… Is lateness always an indication of life, or can it emerge through a recognition that the end is near?”

Franz Schubert: String Quintet in C Major (D. 956) “Allegro ma non troppo”

Mortality

Schubert contracted syphilis in 1822, and within a few weeks, he began to exhibit symptoms, including symmetrical rashes on the palms of his hands, headaches, dizziness, and the loss of his voice. As he tellingly wrote to Leopold Kupelwieser in March 1824, “I feel myself to be the most unhappy and wretched creature in the world. Imagine a man whose health will never be right again, and who in sheer despair over this ever makes things worse and worse, instead of better; imagine a man, I say, whose most brilliant hopes have perished, for whom the felicity of love and friendship have nothing to offer but at best pain…”

However, Schubert clearly had future professional ambitions. “Of songs, I have written many new ones,” he reports, “and I have tried my hand at several instrumental works.” And he writes to his brother shortly thereafter, “True, it is no longer that happy time during which each object seems to us to be surrounded by a youthful gloriole, but a period of fateful recognition of a miserable reality, which I endeavour to beautify as far as possible by my imagination. I am better able now to find happiness and peace in myself than I was then.”

Franz Schubert: String Quintet in C Major (D. 956) “Adagio”

Stylistic Evolution

Schubert’s String Quintet D. 956 score cover

There is much debate as to whether Schubert’s compositional style developed after 1822 through a confrontation with his own mortality or as part of a natural stylistic evolution. For some scholars and performers, “everything Schubert wrote after 1823 was produced under the star of looming mortality,” while more cautious opinions suggest that “Schubert’s style was already in a state of development before the period of illness.”

While these two strands of conflicting thoughts are not easily resolved, it has also been suggested that Schubert approached composition with a “new seriousness, subjectivity, and rigorous self-examination that go well beyond the pleasure principle of cosy Schubertiades. The integrity he attained suggests that he no longer wrote music solely for the delight of companions, the profit of publishers, or the entertainment of the public. He was now writing essentially for himself and for the future.”

Franz Schubert: String Quintet in C Major (D. 956) “Scherzo” (Guarneri Quartet)

Embracing Everything

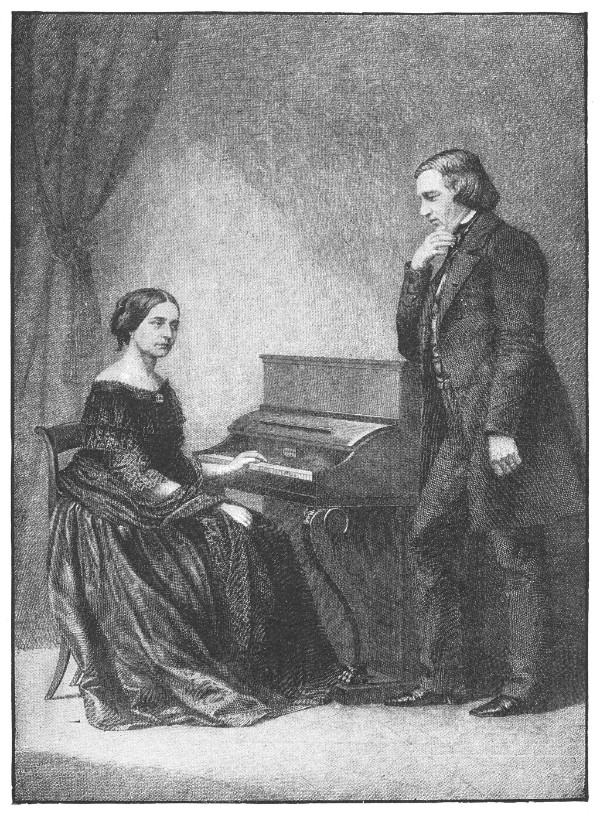

A Schubert Evening in a Vienna Salon by Julius Schmid

The C-Major Quintet contains aspects of innocent beauty and sheer terror. It is essentially symphonic in character, simultaneously drawing on Schubert’s emotional turmoil and on universal yearnings. For Krzystztof Chorzelski, violist with the Belcea Quartet, the C-Major Quintet, more than any other work, “embraces every side of Schubert: exquisite lyricism, Viennese Gemütlichkeit in the finale’s theme for two cellos, intense pathos and, in parts of the first movement and finale, a titanic sense of struggle.” At the center, the “Adagio” is one of the most tormented outbursts in all music. It is an outer-worldly hymn, encompassing passion and emotional intensity projected against the anxiety and desperation of the human experience.

As tranquil intimacy and popular dance music contrast with brooding and menacing passages, it becomes immediately obvious why it is so difficult to write about matters of style. Yet, the work is irresistible as “Schubert’s musical vision is born from anxiety, misery and fleeting hope.” In my personal opinion, no other work so perfectly encapsulates the contradictory and complementary aspects of human existence in musical contrasts between destabilized harmonies exposed to harsh dissonances, and tender themes expressing perfection of balance and contentment.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

As with the Grand Duo, this work very strongly suggests an orchestral symphonic setting, particularly in the latter two movements. I consider this a lesson to the effect that oftentimes in regarding a work of music, it can be necessary to look beyond merely what is handed down to us.