Modest Mussorgsky

When many composers work, they start with a piano score – just getting the basic melody and harmonies down. If they’re going on to create an orchestral work, many composers start with the piano score and fill that out as they start on the task of orchestration. The ideas in the piano score are augmented with the world of sounds that an orchestra can provide: the warmth of the clarinets, the piercing sound of the piccolo, the enveloping sound of the low strings.

We’re familiar with this from works such as Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition, which started out as a piano piece and is much more familiar in its orchestrated version, whether you mean the one by Tushmalov (1891), Wood (1915), Funtek (1922), or Ravel (1922), the latter being the most popular. Even Ravel’s orchestration, still others jumped on the Mussorgsky bandwagon: Leonardi (1924), Cailliet (1937), Stokowski (1939), Goehr (1942) all made their own orchestrations of Mussorgsky’s orignal… the list goes on and on.

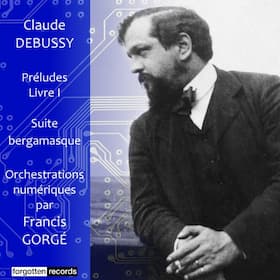

Claude Debussy

When the orchestral colour is added, the piece changes. Often, we hear new lines that were hidden in the piano version, or the orchestrator chooses to emphasize something that came out of his careful analysis.

The French composer Francis Gorgé has been working on the music of Claude Debussy, taking some original piano works in for orchestration: the Preludes, Book I, and the Suite Bergamasque. These were orchestrated earlier, the first for the Hallé Orchestra in 2001 and the second by André Caplet in Debussy’s time. In his notes Gorgé described his working method, which, unlike the others, was a completely digital process.

Francis Gorgé

First, using CAM (Computer Assisted Music) software, he writes out the score, note by note, into the computer. This fills one track. Next, he starts to create new tracks, one for each instrument or groups of instruments. Once he’s decided what notes the violins, for example, will play, he adds the articulation such as the marks for sustained or pizzicato sounds. More instruments are added: woodwinds, a doubling on harp. Although a virtual instrument, technically, has no limitations, he’s always guided by his ear. If this legato bassoon line doesn’t sound right, then it must be changed. Next come the choices guiding interpretation. Sound and timbre can be adjusted and micro-adjustments can be made concerning the attack of the notes, duration, placement, etc. finally, it’s tempo, accelerandos and ritardandos added as necessary. With such fine control of his instruments, Gorgé becomes the ultimate orchestrator and performer in one. The full power of interpretation is in his hands.

It’s the last part – the adjustments for time and tempo that turn the work from a mechanical exercise into a piece of music that adds something important to the musical world. As one person noted, this also frees the orchestrator from the surprises visited upon it by performer and conductor alike. He doesn’t have to worry about engaging a performer who will play only a note or two in the entire work – it’s all digital.

The other side of this lies in the trust the listener has to put in the orchestrator to know the style appropriate for the music and the composer he’s arranging. And, in this, Gorgé has done a lovely job. His imagination both for the style of Debussy’s music and for the scene he’s setting comes across beautifully.

We spoke with Mr. Gorgé and he said that one of the problems with working digitally was that it was difficult to get a complete view of the entire score at once – he’d need a monitor so big as to be impossible. He can see one or two voices at once and concentrates on those.

When he starts each work, he says it’s important to already have an idea of the orchestration ahead of time. A work can take him just a few days or up to a month to orchestrate. It’s also important to finish it and let it alone for a time before taking a new listen – and readjusting things again as he listens to it with new ears.

When he starts each work, he says it’s important to already have an idea of the orchestration ahead of time. A work can take him just a few days or up to a month to orchestrate. It’s also important to finish it and let it alone for a time before taking a new listen – and readjusting things again as he listens to it with new ears.

In his work, he strives to maintain Debussy’s innate style, things shouldn’t be too heavy and he wants to hear the individual voices. He finds that some combinations of instruments are better than others as he experiments.

Claude Debussy: Preludes, Book I – Les Collines d’Anacapri (Francis Gorgé)

We asked Gorgé why he was orchestrating Debussy, since it had been done before. One of the principal reasons was his dissatisfaction with earlier work. Many of the orchestrations had been created for large symphonic orchestras and he was more interested in creating them for his smaller digital ensemble. Impressionism is better on a smaller scale.

Claude Debussy: Suite Bergamasque – Passepiedi (Francis Gorgé)

Having completed the Preludes Book 1 he’s now in the middle of Book 2 and after that, has been looking at works by Ravel, such as Miroirs. As an orchestrator, he’s facing a complete change in style – Ravel’s music is very pianistic, very complex and a very different proposition than what he’s learned after working on Debussy. Satie may be another composer to consider next.

Listen to Debussy with new ears – Francis Gorgé has found a new way to help us hear a master.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter