On 27 July 2024, we celebrate the 100th anniversary of Ferruccio Busoni’s (1866-1924) death. At the time of his passing, he was widely remembered as a pianist with legendary technique, “but his activities as composer and author usually received only passing mention, while his role as a teacher was largely forgotten, except by his pupils.” Busoni always strove to reconcile tradition with innovation, and his essay on the unity of music aimed for the “mastery, examination and exploitation of everything gained from previous experiments, while avoiding the bizarre aping of the multitude of possible ingredients music history could provide.”

In honour of Busoni’s anniversary, we decided to look at some of his earliest character pieces for clarinet and piano, specifically the Suite for Clarinet and Piano, Op. 10. Why did he write clarinet music that early in his life? Well, Busoni grew up in a musical family as his father was an Italian clarinettist, and his mother a German pianist. He was certainly acquainted with the clarinet from early on, and he later even wrote his own three-part clarinet method. As such, it is hardly surprising that his very early attempts at compositions were pieces for the instruments of his parents.

Ferruccio Busoni: Suite for Clarinet and Piano, Op. 10 “Impromptu: Allegro” (Dimitri Ashkenazy, clarinet; Vovka Ashkenazy, piano)

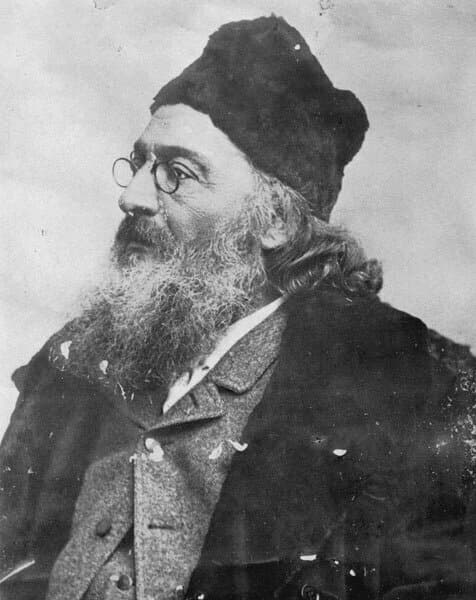

Ferdinando Busoni: The Father

Ferdinando Busoni

The composer’s father, Ferdinando Busoni, was naturally gifted in music, but he never received systematic training. He learned to play the clarinet as a boy and worked with local bands and orchestras, but eventually, he adopted the career of a travelling virtuoso. A scholar writes, “his lack of conventional musicianship made him unfitted for a permanent post in an orchestra, and his quarrelsome temper injured him when he stayed more than a few days in one place.” It was suggested that he was a poor sight-reader and that his sense of rhythm was erratic, however, his performances on the clarinet were considered quite extraordinary.

Ferruccio described his father as “a clarinettist who handled his instrument as a soloist in a special way, sometimes drawing inspiration from the violin, sometimes from Italian vocal music. During his lifetime, he turned his nose up at playing in an orchestra, partly out of pride and partly because he was a natural artist who largely followed his instincts.” Ferdinando was said to have been strikingly handsome in the style of this day, “with a luxuriant brown beard and a somewhat theatrically romantic appearance.” Allegedly, he was involved in countless love affairs with ladies of the Italian aristocracy. On a fateful afternoon, he played at Trieste and was accompanied by a young local pianist, Signorina Anna Weiss.

Ferruccio Busoni: Suite for Clarinet and Piano, Op. 10 “Barcarola: Allegretto” (Dimitri Ashkenazy, clarinet; Vovka Ashkenazy, piano)

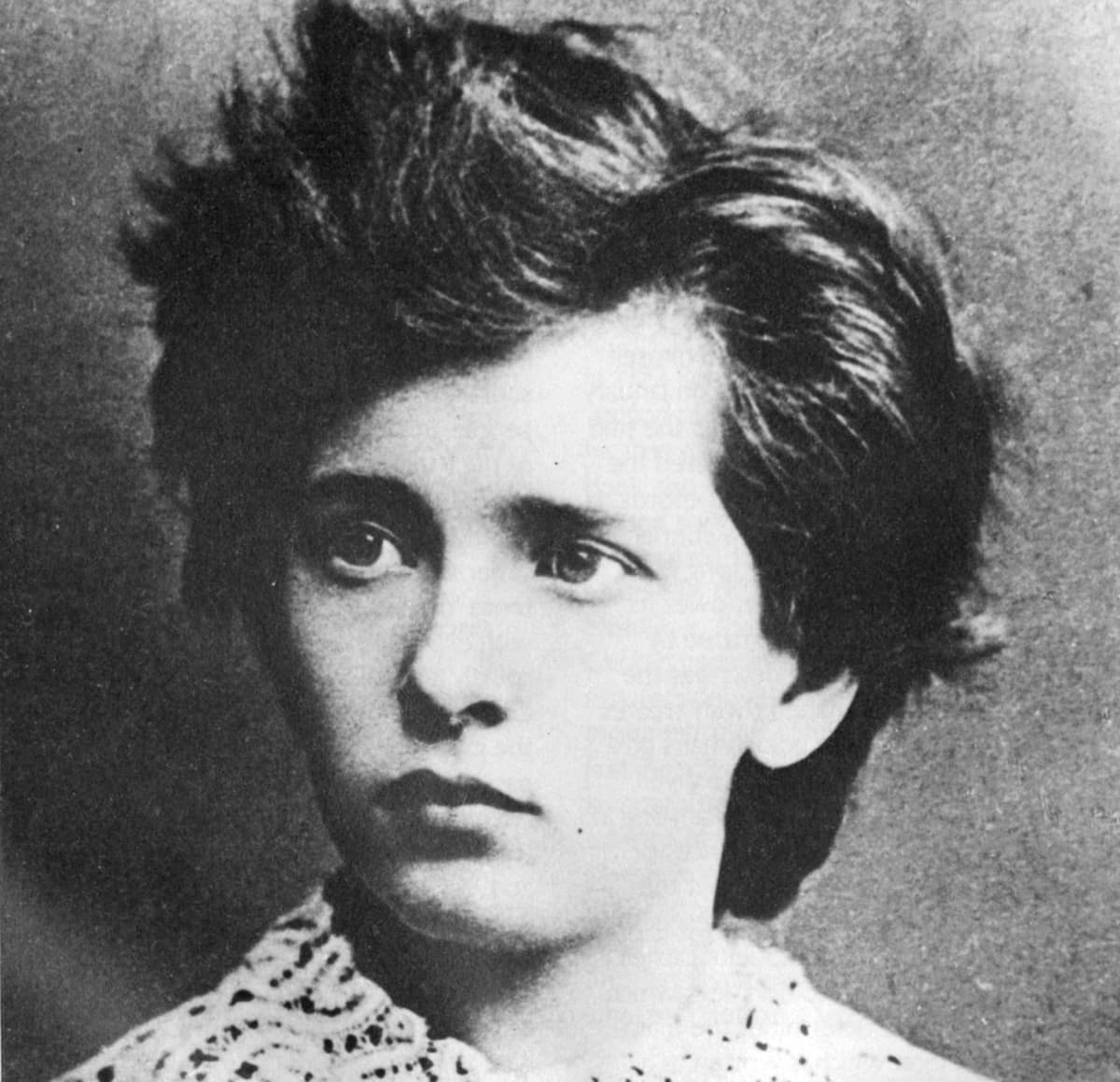

Anna Weiss: The Mother

Anna Weiss

As it happens, Anna fell in love with Ferdinando at first sight. She had had many suitors, but her father thought none of them good enough for her. Now that she had rounded thirty, she was ready to make her own decisions. Her father’s ancestry hailed from Bavaria, but he had been born and educated in Laibach (Ljubljana). He later established himself in Trieste, and he raised his children with considerable strictness. Anna’s musical gifts were apparent at an early age, and she was given every opportunity to cultivate them. She made her debut as a pianist at the age of 14 and, in subsequent recitals, presented her own composition.

According to contemporary reports, audiences were simply enraptured by the delicacy and precision of her execution and “a fairy-like appearance and the ecstatic devotion with which the child threw herself into the expression of her music.” Over the years, she became a local celebrity in Trieste, and she also gave a series of recitals in Vienna. When Anna’s father had a look at Ferdinando Busoni, he quickly saw a “scoundrel who sought popular applause and who had no great love for hard work.” He essentially told him to get lost, but Anna insisted and Ferdinando and Anna were married a few weeks later.

Ferruccio Busoni: Suite for Clarinet and Piano, Op. 10 “Elegia: Adagio” (Dimitri Ashkenazy, clarinet; Vovka Ashkenazy, piano)

Ferruccio Busoni

Ferruccio Busoni

With typical flair, their son was baptised “Ferruccio Dante Michelangelo Benvenuto,” and the child was deposited with his grandmother while the parents went on tour. Ferdinando and Anna settled in Paris, and young Ferruccio “had reached the most delightful age of childhood and was developing rapidly both in body and in mind.” His musical aptitude was truly astounding, and a proud mother writes, “he sits at the pianoforte like an angel, and holds his violin as if he had been practicing for three years. He has a little toy flute too, on which he accompanies my pieces… He is all music and when he hears a beautiful melody he dances and jumps for joy.”

Rumours of the impending war of 1870 caused the Busoni family to leave Paris, with Ferdinando continuing his travels and Anna and Ferruccio returning to Trieste. Ferruccio made rapid progress in his musical and general education, and he reports to his father, “I have an hour’s lesson on the pianoforte every day with Mamma, and I take assiduous lessons on the violin. I hope to do credit to myself in my studies and thus to endear myself the more to my beloved parents.” When Ferdinando unexpectedly returned home, Ferruccio reports, “from that evening onwards my life underwent a complete change.”

Ferruccio Busoni: Suite for Clarinet and Piano, Op. 10 “Danza campestre” (Dimitri Ashkenazy, clarinet; Vovka Ashkenazy, piano)

Lessons from Hell

Ferdinando quickly decided that Anna was too gentle a teacher of Ferruccio, and that the obvious talents of the boy could translate into money. As such, he took charge of the boy’s musical education, and Ferruccio writes in his autobiography, “my father knew little about the pianoforte and was erratic in rhythm. For four hours a day, he would sit by me at the pianoforte, with an eye on every note and every finger. There was no escape and no interruption except for his explosions of temper, which were violent in the extreme.

A bow on the ears would be followed by copious tears, accompanied by reproaches, threats and terrifying prophecies, after which the scene would end in a great display of paternal emotion, assurances that it was all for my good, and so on to a final reconciliation—the whole story beginning again the next day.” Around the age of 7, Ferruccio first stood on the public stage as a pianist, and he started to compose as well. Until his dying day, Ferruccio was convinced that composition was his truest form of self-expression. With regard to this childhood, however, he wrote, “All through my childhood and all through my youth I had to suffer at the hands of my father, and indeed, it has not come to an end yet.”

Ferruccio Busoni: Suite for Clarinet and Piano, Op. 10 “Tema variato” (Dimitri Ashkenazy, clarinet; Vovka Ashkenazy, piano)

Vienna

Ferruccio Busoni, 1913 (Photo by Varischi & Artico)

Following some local successes in Trieste, Ferdinando decided to bring his nine-year-old son to Vienna. It opened up completely new vistas for the boy as he heard Brahms play, thinking little of him as a pianist, but certainly liking his music. He was accepted into the Conservatory, and quickly became known as “a second Mozart.” He played for Liszt and Anton Rubinstein writes, “the young Ferruccio Busoni has a very remarkable talent both for performance and for composition.”

Within a few months of arriving in Vienna, Ferruccio first performed in the Bösendorfer hall alongside the young violinist Artur Nikisch. Eduard Hanslick was in the audience and wrote, “For so long, there has been no child prodigy that spoke to us as likeably as the young Ferruccio Busoni. Particularly as he has so little of the child prodigy per se, on the contrary, much more the makings of a good musician, both as a pianist as well as a budding composer.”

Hanslick went on to assess Ferruccio’s original compositions and writes, “they reveal the same healthy musical feeling as we enjoyed in his playing; no precocious sentimentality or studied bizarrerie, just naive enjoyment of music making, in lively figuration and little combinatorial arts. Nothing operatic or dancelike, more a remarkably serious, masculine mind, which indicates a dedicated study of Bach.” The Suite for Clarinet and Piano, Op. 10 originates during Ferruccio’s time in Vienna, and it “breathes with the spirit of clear and coherent form, inner equilibrium and a balance between moments of tension and those of peace.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Ferruccio Busoni: Suite for Clarinet and Piano, Op. 10 “Serenata” (Dimitri Ashkenazy, clarinet; Vovka Ashkenazy, piano)