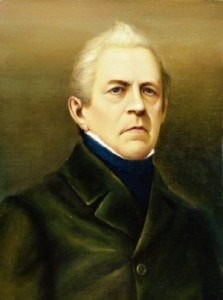

Franz Berwald

Credit: http://www.naxos.com/

Pauer’s key characteristics for A minor are that it is: “expressive of tender, womanly feeling; it is at the same time more effective exhibiting the quiet melancholy sentiment of Northern nations, and curiously enough, lends itself very readily to the description of Oriental character, as shown in Boleros and Mauresque serenades. But A minor also expresses sentiments of devotion mingled with pious resignation.”

Beethoven wrote far fewer works in A minor: 2 violin sonatas, Für Elise, and the String Quartet No. 15. If we take a look at Für Elise, and really listen to it in terms of Pauer’s organization, we might start to hear it in a new way. This Bagatelle for piano, written around 1810, is often one of the first pieces by Beethoven the beginning pianist learns, and usually, grows to ignore as it becomes too familiar. Listen however again – here are two different recordings, the first of which captures the melancholy sentiment that Pauer recognized, and the second, at a faster tempo, seems to rush the intention of the key.

Beethoven: Bagatelle in A Minor, WoO 59, “Für Elise” (Alice Sara Ott, piano)

Beethoven: Bagatelle in A Minor, WoO 59, “Für Elise” (1822 version, ed. B. Cooper) (Ronald Brautigam, piano)

The second version is based on an unpublished 1822 revision of the work Beethoven did when he tried to get a publication together of his ‘bagatelles,’ miscellaneous small piano works. The collection was published in 1867, 40 years after his death in 1827, but did not include this faster 1822 revision.

In terms of looking for a ‘Northern’ composer to fit Pauer’s definition, we have to look at the generations before Sibelius, Grieg, and Nielsen. If we step back in time to Franz Berwald (1796-1868), then we have a composer who fits comfortably into Pauer’s time.

Berwald’s Duo Concertant in A minor for 2 violins might fit the requirements exactly. The first movement, Adagio con espression, seems to have the melancholy sentiment that Pauer felt.

Berwald: Duo Concertant in A Minor for Two Violins: I. Adagio con espression (Tobias Ringborg, violin; David Bergström, violin)

Pauer seems to imbue A minor with characteristics of the ‘other,’ giving it to both ‘northern’ and ‘Oriental’, by which he seems to mean Arab-influenced Spain and Middle-Eastern, countries.

What pieces do you think should be added here? Keep in mind that the piece should date from before 1876, when Pauer’s book was published. Another guideline might be to note the relatively small list of composers he gave as examples: Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Mendelssohn, Schubert Rossini, Weber, and Spohr – all stalwarts of German classicism / romanticism.

Yes, Pauer is totally right about the exoticising, Orientalist nature of A minor! At the very least, Mozart seemed to believe it strongly–Mozart did not use the key too often as the principal key of a work (only the piano sonata K. 310 and the rondo K. 511 come to mind–neither of them is Orientalist as far as I can tell), but there is a rather shockingly high number of times when an A minor intrusion into a larger work signifies the exotic. For example:

– the beginning of the third movement of the piano sonata K. 331, i.e. the famous rondo alla turca

– the middle section of the finale of the violin concerto K. 219, called for this reason the “Turkish” concerto

– the representation of Osmin’s rage at the end of his first aria in Die Entführung aus dem Serail (“erst gekopft, dann gehangen, dann gespießt auf heißen Stangen!”)–this moment is reprised with some abbreviation in the act III finale

– the fandango in the middle of the act III finale of The Marriage of Figaro

I’m not sure about other composers just yet, but the fact that Mozart at least turned to A minor so often for these purposes, while using it so rarely as a “normal” key is striking and clearly meaningful. And even if it was only Mozart who did this (which I doubt), Pauer was clearly looking to Mozart as one of his main models, having studied with his son after all.

Thanks for this series of posts–I always love it any time someone pays lots of attention to key affect, and Pauer is a new name to me!