“I have to warn you, this is not classical music the way you know it”. These were the words of the person sitting behind me before the performance of Feldman’s For Samuel Beckett at the Queen Elizabeth Hall in London, on Friday 29th November. And this could not have been more right indeed.

If I am familiar — and in fact an admirer — of Feldman’s work, this particular one was unknown to me. And I purposely kept it unknown until the performance started. My surprise, therefore, was great.

If the work, as its title suggests, is dedicated to Samuel Beckett, it is not illustrative of anything that the author wrote, however, it reflects on an idea that the author developed. And it is a truly fascinating work.

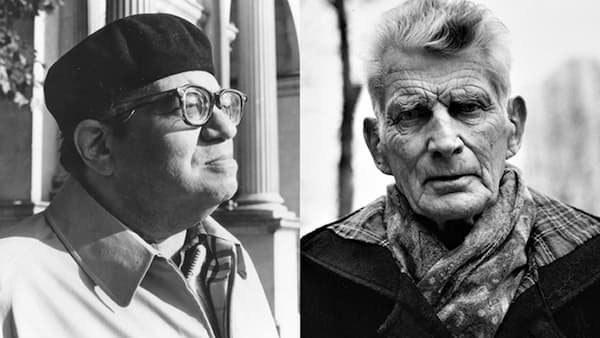

Morton Feldman and Samuel Beckett © bowerbird.org

For Samuel Beckett starts abruptly — one is thrown into this delicate musical vertigo as if it had always been here. Throughout the piece, the music keeps going round in circles, never quite reaching what it should, gently persisting with the sensation of not going anywhere. Creating a sensation of malaise. However, no repetition is ever the same, and through the absence of beginning and ending, it seems that the music simply floats. Just like in Zen Buddhism, the piece seems to have no purpose. This piece indeed reflects on the ideas of Buddhism, and the absence of meaning and intentions. In fact, one seems to ask — where is Feldman going with that? It seems that this has not been defined yet, and this is perhaps what makes For Samuel Beckett such an interesting piece. It goes nowhere and brings the listener to unknown places, in a state of reflection through an absence of direction. The listener is lost, and it is through that confusion that the listener starts to reflect, and perhaps understand.

The instrumentation of the piece is odd; a doubled woodwind quartet, a brass septet, a string quartet, and a trio of harp, piano, and vibraphone. For the performers, it is a challenge. For Samuel Beckett has no beginning, nor end, and keeping track of it is serious mental work.

Queen Elizabeth Hall in London © bynder.southbankcentre.co.uk

In a previous article, I mentioned how minimalism can be divided into two different approaches: one which focuses on the economy of musical sounds and the almost absence of a sense of pace, and the other which looks at maximising the repetition of a small selection of musical ideas, creating a strong sense of pulse. In other words, minimalism and maximalism. Feldman surely belongs to the former in most of his music, however, in For Samuel Beckett, there is a strong sense of pulse, albeit slow and hypnotising.

Morton Feldman – For Samuel Beckett (1987)

Feldman is a minimalistic composer who deserves more attention. It is the perfect missing part between the New York school of Reich and Glass, and the Eastern Holy Minimalism school of Pärt and Tavener. For Samuel Beckett, it is definitely one of his most interesting works.

Some members of the audience decided to leave mid-show — it is true that this creates a particular tension on the listener, testing the ability to accept this absence of intention and clear sense of direction. Like the first time one meditates. And further to that, experiencing this work in a live setting has the wonderful effect of marking the listener in a very distinct way. Almost transcendentally.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter