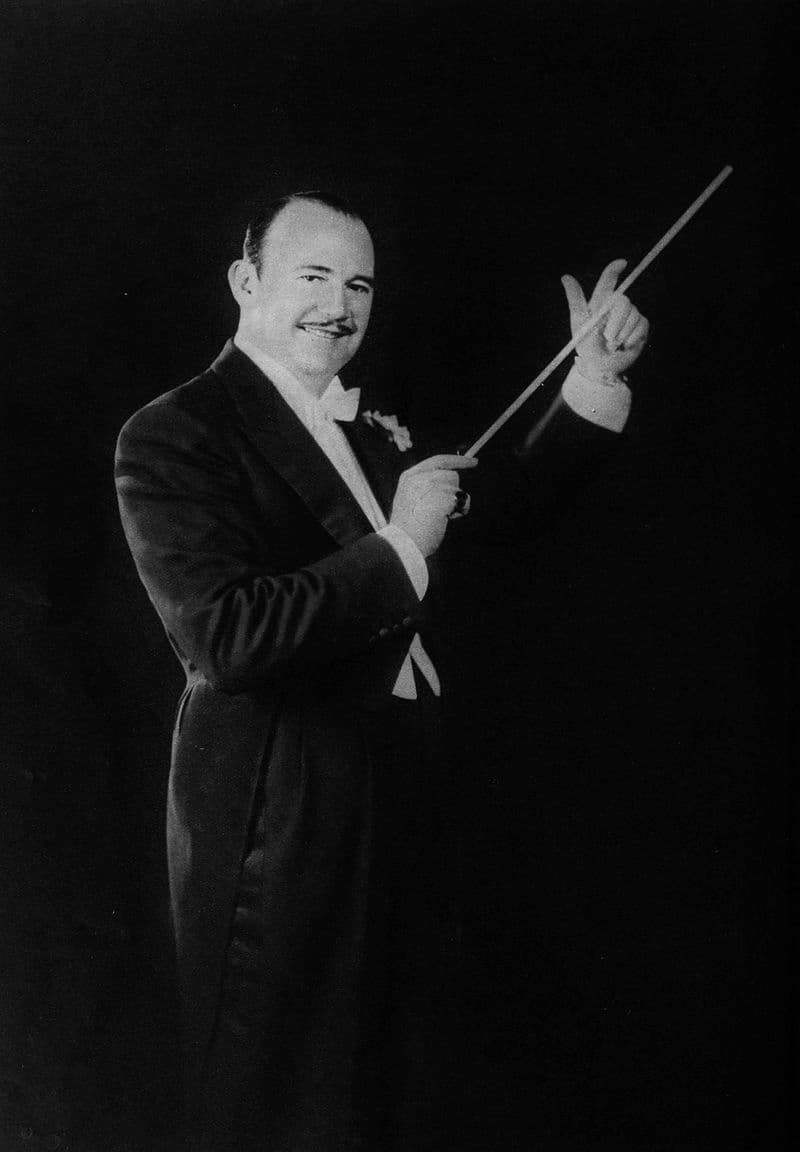

In 1921 Erwin Schulhoff (1894-1942) wrote to Alban Berg. “I have an overwhelming passion for modern dance, and I sometimes even dance night after night with the ladies at the bar… quite simply from enthusiasm for rhythm and from unconscious feeling, which is a phenomenal stimulant for my creative work, bearing in mind that in my conscious state, I am incredibly mundane.” It was Antonin Dvořák who recognized Schulhoff’s talents early on, and after a few years of private study, he entered the Prague Conservatory. He studied with the Smetana student Jose Jirànek, and during a two-year residency at the Leipzig Conservatory, he received composition lessons from Max Reger. Schulhoff embarked on several concert tours, including successful engagements in Paris and London in 1927, and he received the Mendelssohn Prize for piano performance.

Erwin Schulhoff: 5 Etudes de jazz “Charleston” (for Zez Confrey) (Louis Schwizgebel-Wang, piano)

Erwin Schulhoff, 1931

His early composition represented a late Romantic aesthetic, and the works of Max Reger and Richard Strauss greatly influenced Schulhoff. Exposure to the works of Claude Debussy in 1912 fundamentally changed his musical aesthetic, and fighting as a soldier in the Austrian army during World War I left a lasting and pessimistic impression. Post-Romantic expressions had lost all meaning, and Schulhoff was “searching for a new musical aesthetic suitable for his expressive purposes.” He had been exposed to jazz recordings, and the ethos of jazz, particularly the improvised jazz solo and the sensuality of the music, greatly appealed to Schulhoff. “The association of syncopation with primal sensuality could also have underscored subconscious sexual desires brought to the surface,” when African American performers Josephine Baker and Ada Smith danced their way through the cabarets of Paris. The city embraced the exotic sounds of rhythms of jazz, and the avant-garde used it as an inspiration for their own creative world.

Erwin Schulhoff: 5 Etudes de jazz “Blues” (for Paul Whiteman) (Louis Schwizgebel-Wang, piano)

Paul Whiteman

While the world was witnessing a global jazz phenomenon, the spirit of jazz ventured far beyond the Parisian dance hall. Schulhoff’s Cinq Études de Jazz appeared in 1926, and this composition confirms “that jazz was not simply a mere influence on modernism, but a branch of modern art itself. In his openness to engage with the new sounds and rhythms of popular musical entertainment, Schulhoff combined stimulating rhythms with accessible melodies and harmonic refinement.” Each etude is either named for a popular dance or for a subgenre of jazz, and dedicated to a representative musical or artistic personality. The opening “Charleston” originated as a popular social dance in Charleston, South Carolina. Associated with a characteristic syncopated gesture, the dance was made famous in Paris by Josephine Baker. She pointedly observed, “When the rage in New York of colored people, Monsieur Siegfried Folies said it’s getting darker and darker on old Broadway. Since the La Revue Negri came to Gai Parée I’ll say it’s getting darker and darker in Paris.”

Erwin Schulhoff: 5 Etudes de jazz “Chanson” (for Robert Stolz) (Louis Schwizgebel-Wang, piano)

Josephine Baker

“While the popularity of the Charleston provides social commentary on race relations involving the exploitation of black entertainment in Europe and the United States, the jazz subgenre of the blues offered commentary on the social conditions that existed in the southern United States.” As has been suggested, “the melancholic sounds and unfiltered expression of the blues reflected a music that had been crafted by an oppressed people.” For Schulhoff, “Blues reflected the atmosphere of Montmartre as the home of numerous cabarets. This fertile atmosphere that saw the mingling of writers, painters, artists, and musicians openly welcomed the aesthetic of blues music and the poetry it inspired.” Schulhoff’s “Blues” is dedicated to Paul Whiteman, called the “King of Jazz.” Whiteman was instrumental in introducing jazz to mainstream audiences during the 1920s and 30s. In the next etude titled “Chanson” Schulhoff pays homage to the café-concerts and the composer of light-entertainment music, Robert Stolz.

Erwin Schulhoff: 5 Etudes de jazz “Tango” (for Eduard Künnecke)

Eduard Künnecke

The tango originated in the slums of Buenos Aires, Argentina. It combined various influences from Latin American and African traditions. “The rhythmic patterns bear a remote influence of African musical traditions, while the melodies bear a distinctive Latin American influence. Furthermore, the influence of both musical traditions resulted from immigration from Africa and Spain to the West Indies, Central America, and South America.”

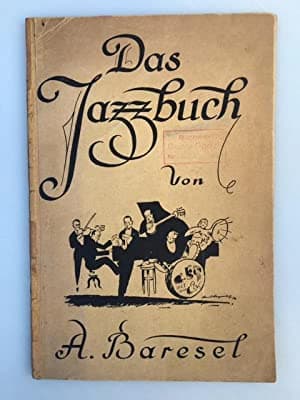

The Book of Jazz – Alfred Baresel

This dance form rapidly spread across the globe and soon was a popular fixture in the cabarets of Montmartre. According to scholars, “Schulhoff’s inclusion of the tango is a nod to the capacity of jazz to readily assimilate any culture.” The concluding “Toccata Sur le Shimmy” is based on an existing piano work published by Zez Confrey in 1921. “While the first four etudes are sonic representations and commentary of the sociopolitical climate and artistic tastes of the Jazz Age in Europe, the concluding etude serves as an epilogue that in itself represents a synthesis of several different musical styles.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Erwin Schulhoff: 5 Etudes de jazz “Toccata sure le shimmy ‘Kitten on the keys’ de Zez Confrey” (for Alfred Baresel) (Louis Schwizgebel-Wang, piano)