Richard Strauss

Richard Strauss (1864 –1949) was the major German opera composer of the late 19th to the mid-20th century. His life and music were controversial during his lifetime and remained so after his death.

One can argue about his music, his writings, his ability to catch the heart of his public but a look at opera programs over the world would quickly settle such discussions. His many operas, including Salome, Elektra, Der Rosenkavalier, Ariadne auf Naxos, Die Frau ohne Schatten and others are on the schedules of all the major opera houses around the world. One of the most recent productions was his 1928 opera Die ägyptische Helena at the magnificent Teatro La Scala, which was nearly full.

Jacques-Louis David: The Love of Helen and Paris by Jacques-Louis David (1788, Louvre, Paris)

Richard Strauss composed this opera working closely with his friend and literary inspiration, Hugo von Hofmannsthal, who was a well-known writer and poet and who contributed to most of his operas. Die ägyptische Helena was the last opera created with von Hofmannsthal who died tragically in 1929 of a stroke at age 55 two days after the funeral of his son who had committed suicide.

Strauss came from a musical family; his father was a member of the Munich orchestra and his mother a singer descended from a wealthy family. Strauss entered the Munich Conservatory studying piano and composition, but soon abandoned piano to dedicate himself full time to composition. A bitter quarrel ensued between Richard, who became totally devoted to the music of Wagner, and his father who was an outspoken anti-Wagnerian. Richard was a long-time Wagner devotee and follower and many of his operas recall Wagner’s works in their choice of historical setting, the characters, and the non-stop singing, which often left the singer, the orchestra, and the public exhausted.

While the factual story of Helen of Troy is straightforward, the philosophical and metaphysical narrative that von Hofmannsthal developed looks more deeply into the jealousies that Helena’s beauty inspired. Helena, who was kidnapped and taken to Troy, has been liberated after the long war and is being taken away by her husband Menelas who succeeded in killing her kidnapper, Paris. Yet, Menelas is determined to kill Helena for her unfaithfulness.

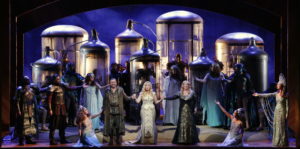

La Scala: Die ägyptische Helena finale (2019)

She is rescued by the sorceress Aithra, who shipwrecks them off her island. Aithra is an oracle, a sorceress, who has great affection for Helena, the most beautiful woman in the world. Aithra helps Helena regain her lost beauty and Melenas is tormented by a spectre of the dead Paris and his jealousy. Both parties are put to sleep by Aithra.

In Act II, Menelas is still uncertain about Helena and now believes her to be a spirit. Prince Altair appears to offer Helena presents. Menelas has a new jealousy and kills Altair’s son on a hunting trip. Aithra gives Helena a potion of remembrance and through this, Helena and Menelas can leave their history behind and, with their daughter Hermione restored to them, start their lives again.

The singing, the stage, the orchestra

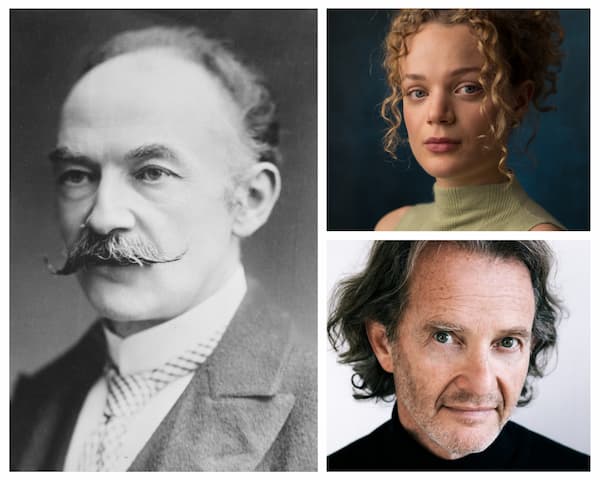

Peter Hermes with Eva Mei

Eva Mei (Aithra) vocally dominates this production through her great volume, superb colour, splendid soffragio. Ms. Mei keeps her instrument infallible, not losing her cue or intensity in high or low registers. Ms. Mei is also a consummate actress, now terrifying, now sweet, now mysterious, and at times erotic, she succeeds in energizing the rest of the cast into this complicated plot. The tercet the end of the first act is a musical highlight.

Ricarda Merbeth (Helena) has an imposing voluminous voice with superb control and a thrilling high register that, however, sounded sometimes strident especially in the first act. She seemed somewhat immobile and her stage presence could benefit from additional adrenaline.

A delightful surprise was young Caterina Maria Sala (Hermione, daughter of Helena), a soloist from the La Scala Academy, who at the end the second act delivered a spectacular aria.

The male cast although of great provenance was less arresting. Menelas, the young German tenor Andreas Schager, was being continuously put in the shadow by Helen and Aithra in spite of a solid voice.

Thomas Hampson (Altair), the world-famous American baritone who is now resident in Vienna, took this minor role. I found his singing to be lacking the golden voice so familiar from his videos and recordings.

In the final moments we have a discreet trio of Helena, Aithra and Menelas whereby the sopranos masterfully cover the tenor. There is Altair’s intervention to save the tortured couple and presently Helena and Menelas can elope happily to their royal home in Sparta.

Franz Welser-Möst, the conductor, has been music director of The Cleveland Orchestra for the past 18 years. He conducted the La Scala orchestra with a sure hand although his head was buried much of the time in the score and he was not seen singing with the soloists as some of the great opera conductors do.

La Scala orchestra sounded first class, responding to all the rhythmic changes and bringing forth a great sound. I counted 7 contrabasses and two harps in addition to the full complement of strings and wind instruments…this is probably today the finest orchestra in Italy.

To Sven-Eric Bechtolf, the designer, we can be grateful that he, unlike other invasive registas, made economical use of the wood contraptions, the significance of which I admit escaped me, which did nothing to hinder the singing or moving of performer across stage.

All in all, it was a musically very challenging afternoon of great voices, a great orchestra, and great

music by Strauss.