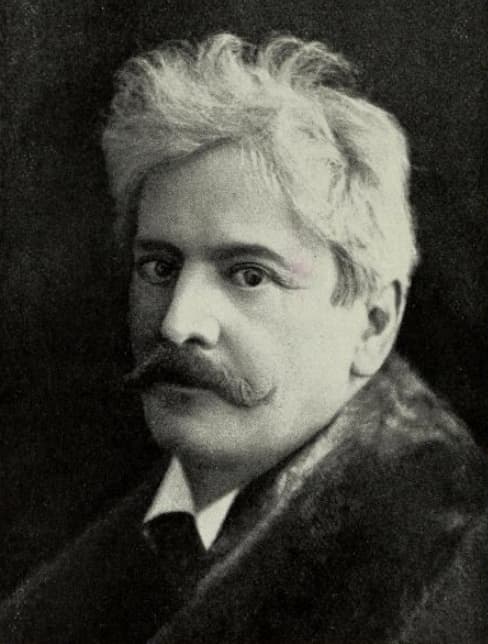

David Popper, born in Prague in 1843, was one of the most influential cellists of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. He was a celebrated virtuoso of his time, lauded for his flawless technique and expressivity, with George Bernard Shaw calling him “the best player in the world.” In addition, he was also an experienced orchestral and a sought-after chamber musician, performing with such greats as Brahms, Liszt, and Hubay.

David Popper

Throughout his active career, Popper travelled and composed non-stop, and his salon pieces were extremely popular. Every self-respecting cellist would play one or two of Popper’s compositions as encores. They are still in the repertoire of cellists across the globe, and these charming virtuoso pieces continue to delight audiences. More than enough reason to get to know some of these works a little better, don’t you think?

David Popper: Suite for 2 Cellos, Op. 16

Paganini of the Cello

The son of a Jewish Cantor at two local synagogues in Prague, young David started taking cello lessons and made phenomenal progress. At the age of fifteen, he was asked to substitute for his teacher, and audiences started to recognize a resemblance between Popper and Paganini. Popper writes, “When I began my public career, everywhere people discovered in my physical appearance a coincidental resemblance to Paganini: this was due mostly to my thinness, bordering on transparency, as well as to my raven, long black hair…”

Popper continued, “It earned me a little halo, which I did not really deserve, during my first independent concert efforts… Many famous musicians who had known Paganini and associated with him were astonished by the similarity of appearance between the young Bohemian knee fiddler and the Italian magician of the violin. The more intense the desire of the people to recapture what had been lost, the more keen the search for a present substitute. They transferred the physical resemblance to my playing and imagined that they heard the demonic sound of the great Italian. These were certainly very promising beginnings.”

David Popper: Suite for Cello and Piano, op. 69 (Laszlo Mezo, cello; Gábor Farkas, piano)

Founder of the Belgian School

The Paganini comparison did play a part in Popper’s first virtuosic concert appearances, but in terms of performing style, he was most frequently, and perhaps surprisingly, associated with Vieuxtemps. Commentators found a similar style, a noble, graceful, elegant, and controlled passion, and a smooth playing style. A noted musicologist actually considers Popper one of the founding cellists of the Belgian school of cello playing. He writes, “We can see that Popper was close to the style of the Franco-Belgian violin and cello school in his very cultured tone and in his elegant phrasing and technique.”

The Belgian school of string playing produced works “in romantic forms best suited to the improvisatory and virtuosic nature of music, influenced by the increasing popularity of opera in the 19th century.” In his extensive catalogue of compositions, Popper preferred to compose in three basic groups: the fantasies, the concertos, and salon music.

David Popper: Sérénade Orientale in G Minor, Op. 18 (Martin Rummel, cello; Mari Kato, piano)

Superstar

A tall and handsome man, Popper developed an irresistible stage charisma. After a performance in December 1868, a critic wrote, “Vienna has had, until now, no cellist to boast about, and none was received with such enthusiasm, other than some foraging artists who appeared on transitory visits. We can congratulate ourselves on the recent acquisition of such an artist in David Popper.” The critic was referring to the fact that Popper had just been appointed principal cellist with the Vienna Philharmonic and the orchestra of the Vienna State Opera.

The new darling of the Viennese music scene perfectly fitted the male superstar look of the 19th century. He was taller than the average individual with a wiry and lean physical frame but with broad shoulders, wavy hair, distinguished facial features, a masculine chin, and a chiseled profile. In fact, musical talent, physical appearance, showmanship, and virtuosity were, and still are, indispensable and intertwined elements of all musical performances.

David Popper: Dance of the Elves

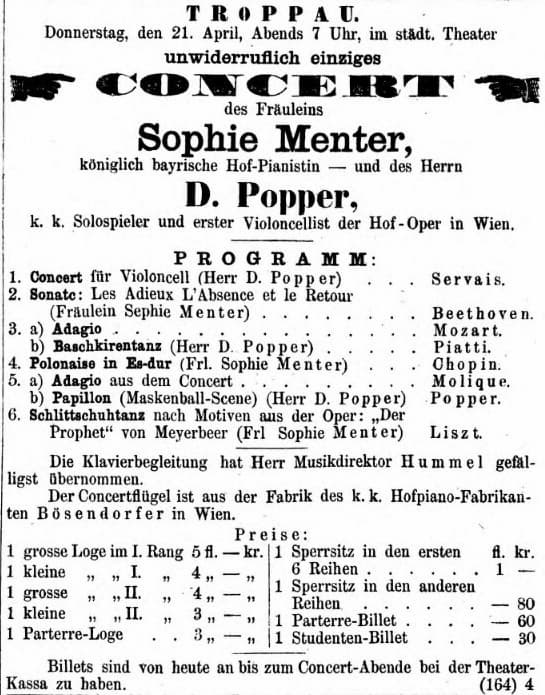

Marriage to Sophie Menter

In 1872 the handsome cello star married Sophie Menter, the greatest woman pianist of the age. Sophie Menter (1846-1918) gave her pianistic debut at age 15, and she took further lessons with the Liszt pupil Carl Tausig. She soon appeared in concerts throughout Europe. Her very first concert in Leipzig featured a composition by Franz Liszt, and the E-flat major concerto became her signature piece. “Miss Menter,” a critic wrote, “deserves the praise of all the other performers of this concert for having reproduced the witty composition in accordance with its true intention.”

Pianist Sophie Menter

Although Liszt called her “my only legitimate piano daughter,” Menter was not actually one of his students. Rather, they looked at each other as colleagues, visited each other, and made music together. Liszt remarked that the Popper/Menter marriage was “Un marriage concertant.” George Bernard Shaw heard Menter in 1890 and wrote, “she produces an effect of magnificence which leaves Paderewski far behind … Mme Menter seems to play with splendid swiftness, yet she never plays faster than the ear can follow, as many players can and do; and it is the distinctness of attack and intention given to each note that makes her execution so irresistibly impetuous.”

David Popper: Fantasy on Little Russian Songs, Op. 43 (Martin Rummel, cello; Mari Kato, piano)

Glamour Couple

Popper and Menter became a true glamour couple of their time, and gossip columns would not stop writing about “the world famous David Popper and his gorgeous wife.” They quickly travelled throughout Europe, Russia, and even embarked on a concert tour of America. This union of two celebrated artists was beloved by the public far and wide, and it certainly added to their fame. However, almost as expected, there was a good bit of rivalry between these two great artists.

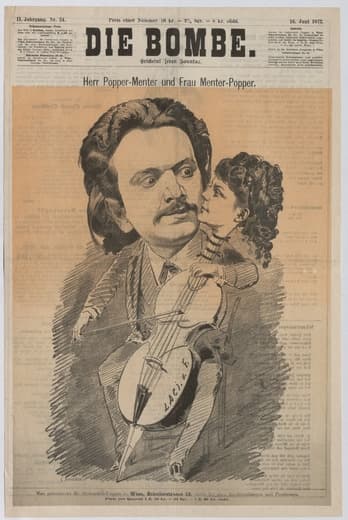

The marriage of Sophie Menter and David Popper

Apparently, they started fighting about such things as who received more applause at the end of a recital. Like Popper, Menter was also busy as a composer. She wrote various pieces for piano, mainly in a brilliant style, yet referred to her own compositional talent as “miserable.” Tension between the glamorous couple was rising, and a funny little anecdote relates that Menter was given the newly composed “Hungarian Rhapsody” by Liszt and secretly studied it. “However, in a joint recital, Popper stole the momentum and played an improvisation on the same theme by Liszt in as virtuosic and entertaining manner as he could. The professional jealousy and tension harmed their marriage, which ended after 14 years.”

David Popper: Hungarian Rhapsody Op. 68

The Performer…

In his performances, Popper’s warm tone and technical perfection saved many compositions from arousing public antagonism. As his biographer writes, “Popper as a virtuoso never suffered from the accusation that his recitals were dull. The qualities of his extraordinary playing often overcame the limitations of a work he was to perform, and the projection of his individuality could enhance even an unimportant composition.”

Poppers’ own compositions were in high demand in public appearances and private salons. Apparently, Popper was able to “discriminate effectively in producing music which satisfied the demand for appealing music, and elevated the standard of cello salon literature, while incorporating a special touch of originality and new technical effects.” Even the usually grumpy Eduard Hanslick stated, “Popper has composed a number of very effective bravura pieces… His pieces found acclaim everywhere, and are also played by other virtuosos, and sell well. This all proves their practical value. They are cleverly made little things, which betray more coquettishness than creative strength.”

David Popper: Im Walde, Op. 50 (Martin Rummel, cello; Gerda Guttenberg, piano)

… and Composer

The press excerpt titled “Die Bombe” about the relationship of David Popper and Sophie Menter

Popper was considered the perfect blend of charm, personality, and virtuosity. “When we see and hear him perform,” wrote a critic, “our soul is harmoniously filled with charm and joy. Whenever the name David Popper is mentioned, from deep in our memories we recall his nobly featured head leaning over his instrument, the controlled elegance of his bow-arm, the clear sweet tone welling from his cello, and the graceful, harmonious winding melodies blending with the colourful fireworks of virtuosity.”

David Popper: Spinning Song

A good many of Popper’s most rousing compositions were arranged for the violin by such greats as Auer, Sauret, Herrmann, Neruda, and others. Predictably, some critics accused Popper of being superficial in his compositions, but to this day cellists enjoy playing his delightful character pieces and dances. David Popper died of a heart attack in the evening of 7 August 1913 in the resort town of Baden bei Wien. According to his wishes, he received a stab in the heart before cremation, and his ashes are buried in close proximity to the remains of his son in Dresden.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter