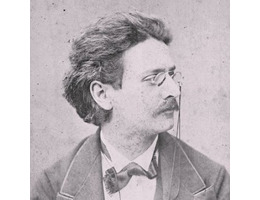

The Dandy

David Popper

Ungarischer Rhapsodie, Op. 68

Im Walde, Op. 50

David Popper (1843-1913) had a remarkable aptitude for the cello — although he first started on violin — and was taught by the Hamburg cellist Julius Goltermann at the Prague Conservatory. When David reached the tender age of eighteen, he had not only developed into a cellist of extraordinary ability, but also grown into a dapper and dandy young man. On his first tour to Germany, he caught the eye of Hans von Bülow — famed pianist, conductor and Franz Liszt’s son-in-law — who recommended him for a position at the court of the Prince Friedrich Wilhelm Konstantin von Hohenzollern in Löwenberg. His natural flair and flowing hair immediately attracted the attention of the composer Robert Volkmann, who had just finished work on his cello concerto Op. 33. Although many extraordinary cellists — among them Piatti, Servais, Davidov, Grützmacher and Franchomme — were active at that time, the honor of giving the premiere performance of the work in 1864 rested with David Popper.

Sophie Menter

By 1868 he had secured the position of principal cellist of the Vienna opera, a position he held for five years. In 1872 he married Sophie Menter, a former Liszt student and considered the greatest woman pianist of the age, and the happy couple embarked on a series of concert tours throughout Europe and Russia. Popper eventually settled in Hungary in 1886, where he accepted a position at the Academy of Music in Budapest. Together with the violinist Jenö Hubay, Popper formed the Budapest String Quartet and Johannes Brahms joined them in the premiere performance of his Op. 87 Piano Trio. As a performer — he was the last great cellist to perform without an endpin — Popper was described as graceful and elegant, effortlessly capable of navigating the most demanding levels of virtuosity. This combination of musical expressiveness and technical prowess naturally informs his roughly one hundred compositions, predominantly scored for cello and piano. Many of his works take the form of character miniatures and are known under evocative titles, like Gnomentanz (Dance of the Gnomes), Elfentanz (Dance of the Elves), Serenade, Spinnlied (Spinning Song), and Tarantelle. He also composed a number of cello concertos and his own cadenzas to the concertos by Haydn, Schumann, Saint-Saëns, Volkmann and Molique. Among his most unusual and moving compositions is the Requiem for Three Cellos and Piano, Op. 66, composed in 1892 and dedicated to the memory of his friend and first publisher Daniel Rahter of Hamburg. Elegiac and melancholic, the work was also performed at Popper’s own funeral in 1913. Popper’s most valuable contribution to the art of cello playing is his didactic publication High School of Cello Playing, Op. 73. It contains forty etudes that are universally recognized as an integral part of advanced cello instruction. Talent and looks, David Popper had it all!