On 1 February 1908 Emilia Manfredi filed a formal lawsuit charging Elvira Puccini with causing the suicide of her daughter Doria. Subjected to continual and blatant defamation, the lawsuit read, Doria Manfredi had swallowed a lethal amount of sublimate, a corrosive poison used as a disinfectant. The young woman did not die immediately but suffered excruciating pain for five days as the poison slowly ate her alive.

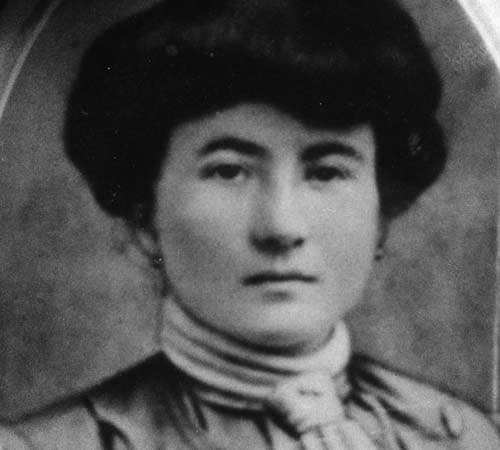

Elvira Puccini

The magistrate proclaimed that the case was to be heard, and on 6 July 1909 the trial began in Lucca. Elvira Puccini was charged and found guilty on three different counts; defamation of character, libel, and menace to life and limb. Elvira did not make a court appearance but stayed in Milan feigning illness, and thus offered no defense against the accusations. Emilia’s deposition produced a post-mortem report that her daughter Doria had still been a virgin, and that “the wife of the composer had started a war against her daughter made up of abuses.”

Eventually, the Court found “Elvira Bonturi Puccini guilty of the crimes ascribed to her and sentences her therefore to the overall punishment of five months and five days of confinement, and a fine of 700 lira. She is also responsible for all court expenses.” A young woman dead, the wife of the famous composer sentenced to jail and an opera composition that seemed to go nowhere; how did we get to this sad state of affairs?

Giacomo Puccini: La fanciulla del West, “Una partita a poker!” Act II (Carol Neblett, soprano; Sherrill Milnes, baritone; Royal Opera House Orchestra, Covent Garden; Zubin Mehta, cond.)

Doria Manfredi

It all started eight years earlier when Puccini was working on Madama Butterfly. He fell in love with a pretty young girl named Corinna he had met in Turin, and there is some suggestion that he proposed marriage to her. At that time, Puccini was living with Elvira Bonturi, who was still married to somebody else. Things seemed to get out of hand, but then, on 25 February 1903, Puccini suffered a severe car accident. He was seriously hurt and needed someone at home to take care of him. As such, Elvira hired the local girl, Doria Manfredi, to care for Puccini. By a strange coincidence, Elvira became a widow the very next day. In the event, it took Puccini nearly a year to recover from his injuries, and during that time, Doria became part of the Puccini household.

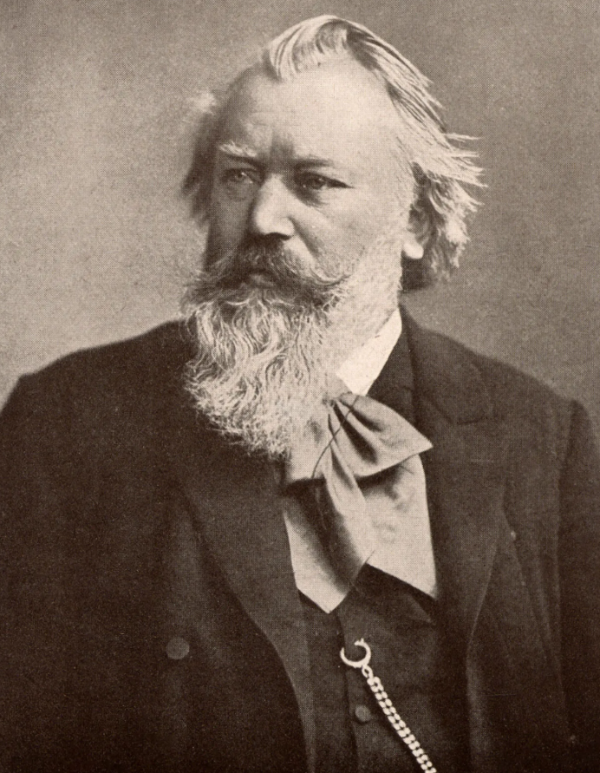

Giacomo Puccini and Elvira Puccini

But Puccini was still crazy about Corinna, and he hired a private detective who discovered that the girl was not as innocent as she pretended to be. He wrote her an angry note, “What an abyss of depravity and prostitution! You are a shit, and with this, I leave you to your future.” Corinna would have none of it and threatened legal action, and she was ready to go public over the affair. Puccini panicked, but he was eventually semi-successful in explaining to Elvira the “real meaning” of the letter she received from Corinna.

Giacomo Puccini: Madama Butterfly, “Un Bel di Vedremo” Act II

Thus primed and ready, in the autumn of 1908, Elvira became violently jealous and suspected that her husband was having an affair with the housemaid Doria Manfredi. Puccini did, in fact, have an affair, but it was not with Doria but with her cousin, Giulia Manfredi. Torre del Lago was rife with gossip, and by sheer accident, Doria discovered that Puccini’s stepdaughter Fosca, who was married to the impresario Salvatore Leonardi, was having a fling with the librettist Guelfo Civinini in the Villa Puccini. Fosca was terrified that the affair should be made public and decided to discredit Doria by accusing her of having an affair with her stepfather. And it was at this point that Elvira began her fierce campaign of harassment and persecution of Doria. Elvira summarily dismissed Doria and informed as many villagers as possible that Doria had an affair with her husband. She publically called her a “whore and a tart” and “a tramp who ran after my husband.” Sooner or later, Elvira asserted, “I will drown her in the lake.” Doria was probably innocent, but she could not defend herself without betraying both her cousin and the maestro. Unable to bear the pressure, Doria, aged 23, swallowed the corrosive poison.

Giacomo Puccini: La fanciulla del West, “Io non son che une povera fanciulla” Act I (Emily Magee, soprano; San Carlo Theatre Orchestra; Juraj Valčuha, cond.)

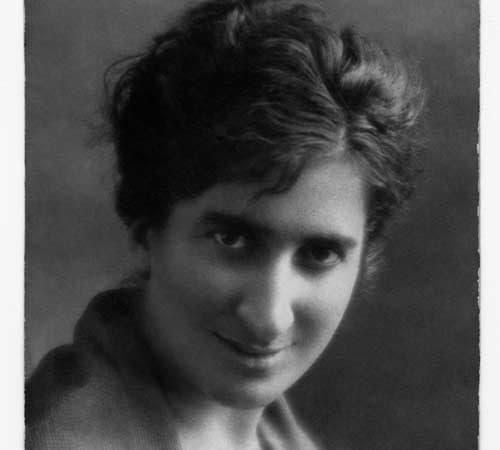

Giulia Manfredi

The trial verdict was widely publicised, and Elvira wrote to her husband. “Today, the news is all over other newspapers as well. And they want to avoid scandals! It would have been less scandalous if it were known to everybody that you had an affair with the servant rather than the outcome of the trial. Are you convinced now that Doria’s relatives have been the most disgusting in all this?” Unbeknownst to Elvira, Puccini secretly negotiated with the Manfredis family to drop the charges in exchange for a large cash payment. Arrangements were finally agreed upon, and the family received a settlement of 12,000 lire. As a result, the Court of Appeal declared the action extinct on 2 October. The composer writes, “Elvira seems to me to have changed a great deal due to the hardship of the separation, which she has endured—and so I hope to have a little pace and to be able to get on with my work.” So, what is the moral of this sordid tale? It was Puccini’s pursuit of women that created this crisis in the first place, leading to infidelity, jealousy, vengeance, despair, and the death of young women. It has even been suggested that Puccini might have had an affair with Doria but “paid” for the correct post-mortem results. In the end, as the world keeps spinning, money once again wins the day.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter