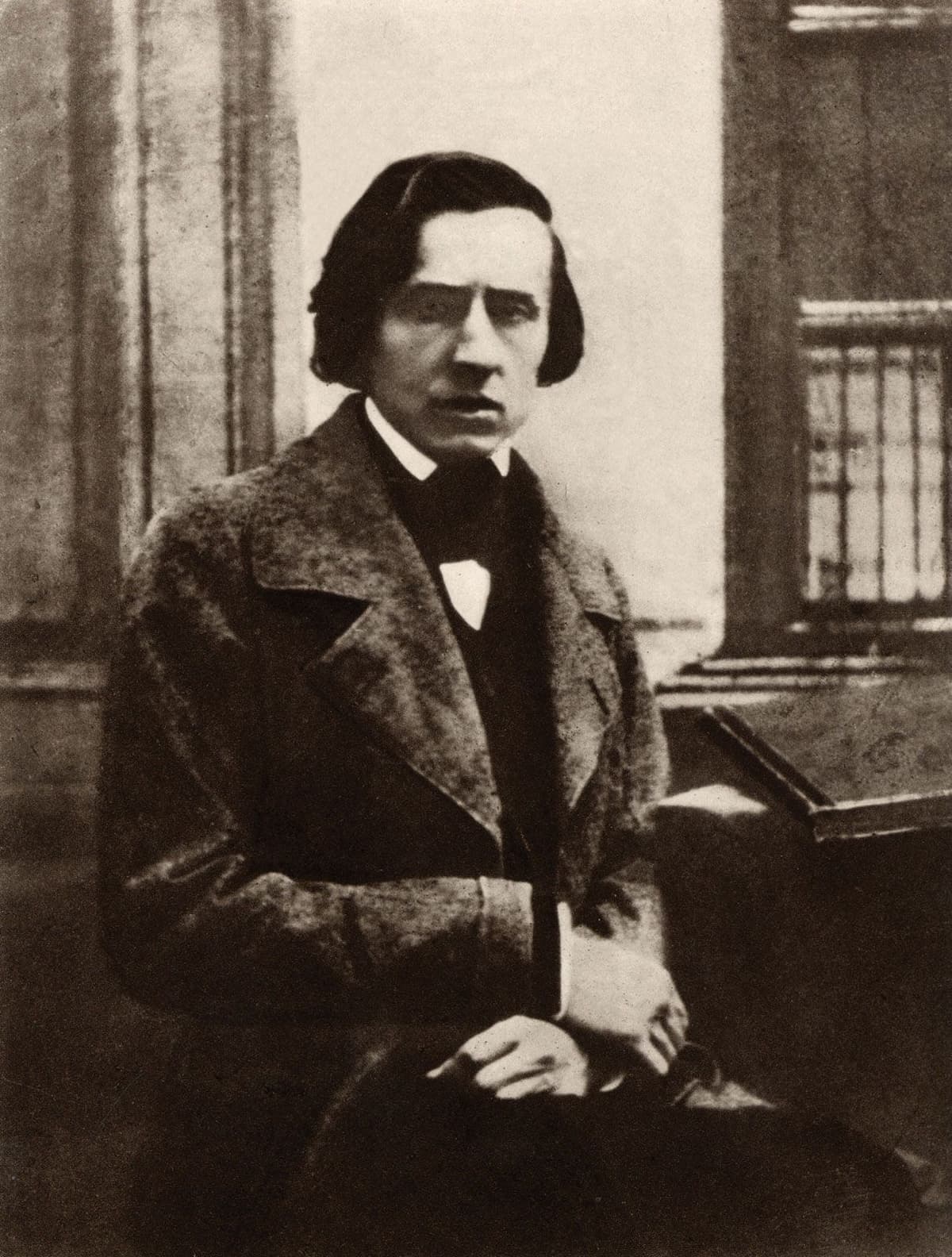

Frédéric Chopin (1810-1849) had a wonderous gift for combining melody with an adventurous harmonic sense. Paired with an intuitive understanding of formal design and a brilliant piano technique, Chopin composed some of the most beloved compositions in Classical music. And while we have no problems coming up with a list of his most popular compositions, there are still works lurking in the composer’s oeuvre that are hardly known.

Frédéric Chopin

Among these neglected works are the Polish Melodies, Op. 74, composed between 1828 and 1845 and collected and published posthumously. Chopin actually did not approve of his songs being published at all, as he considered them “reflections of his very soul.”

In my article The Music of Poetry: Chopin’s Polish Songs, I have provided some background to Chopin’s choice of poets and poetry and discovered “the simplicity of a first-hand folkloric inspiration, an almost naive, youthful tenderness, a boisterous aplomb, a nostalgic reflection, and finally a deep feeling for one’s country.”

Liszt/Chopin: 6 Polish Songs, No. 1 “Mädchens Wunsch”

Liszt and Chopin

Chopin and Liszt

In Chopin’s Opus 74 we find nineteen songs, and Franz Liszt transcribed six of them for piano. Chopin’s relationship with Liszt was often a rather stormy affair, but they clearly had plenty of mutual respect for each other. They had first met in 1831, shortly after Chopin had arrived in Paris. As a critic writes, “their association was unlucky at best and often flawed by misunderstanding and little warmth.”

According to an anecdote, the relationship between the two artists suffered a serious blow when Liszt used Chopin’s lodgings during his friend’s absence for a tryst with Marie Pleyel. Since Chopin was a close friend of Camille Pleyel, Marie’s mother, Liszt’ conduct left him in a rather uncomfortable position.

When Chopin gave a concert in Salle Pleyel in Paris on 26 April 1841, Liszt wrote a long review that was open to varying interpretations. While Liszt expressed his unequivocal admiration for his fellow artist, he did not praise Chopin as a composer. Chopin, his circle of friends, and his family members took great offense.

Liszt/Chopin: 6 Polish Songs, No. 2 “Frühling”

Chopin Monument

It has been suggested that Liszt may well have been jealous of Chopin. Apparently, he was greatly incensed that he was only seen as a virtuoso. His compositions, unlike those of Chopin, “were hardly met with a single word of praise.” Chopin had increasingly distanced himself from the works of Liszt and his breathtaking virtuosity and style, and it might have aided Chopin’s escape into self-imposed seclusion.

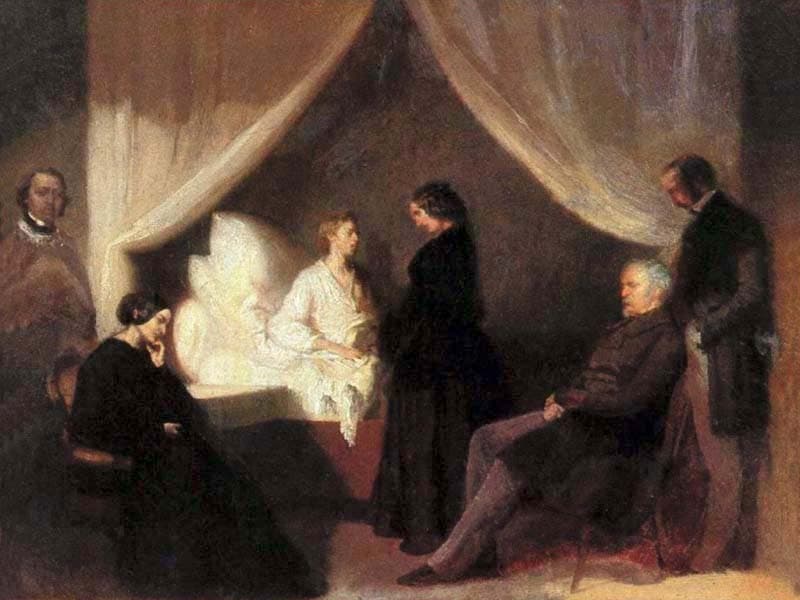

Chopin on His Deathbed, by Kwiatkowski, 1849, commissioned by Jane Stirling.

Liszt and Chopin met for the last time in December 1845, and after Chopin’s death in October 1849, Liszt had a monument erected in memory of his fellow artist. He also started to write the first monograph on Chopin’s life and work, in essence becoming Chopin’s first biographer.

Simply titled “F. Chopin by F. Liszt,” the author quickly underscores that their names alone need no further explanations. Yet, Liszt did need some reliable information before starting to write his Chopin biography, and he turned to Chopin’s sister Ludwika for questions. The family was not amused getting questions about the relationship between Chopin and Sand a mere two weeks after the composer’s funeral. Ludwika strongly suggested that Liszt contact the “official widow,” Jane Stirling, one of Chopin’s former students. However, she was not talking either.

Liszt/Chopin: 6 Polish Songs, No. 3 “Das Ringlein” (Elena Rozanova, piano)

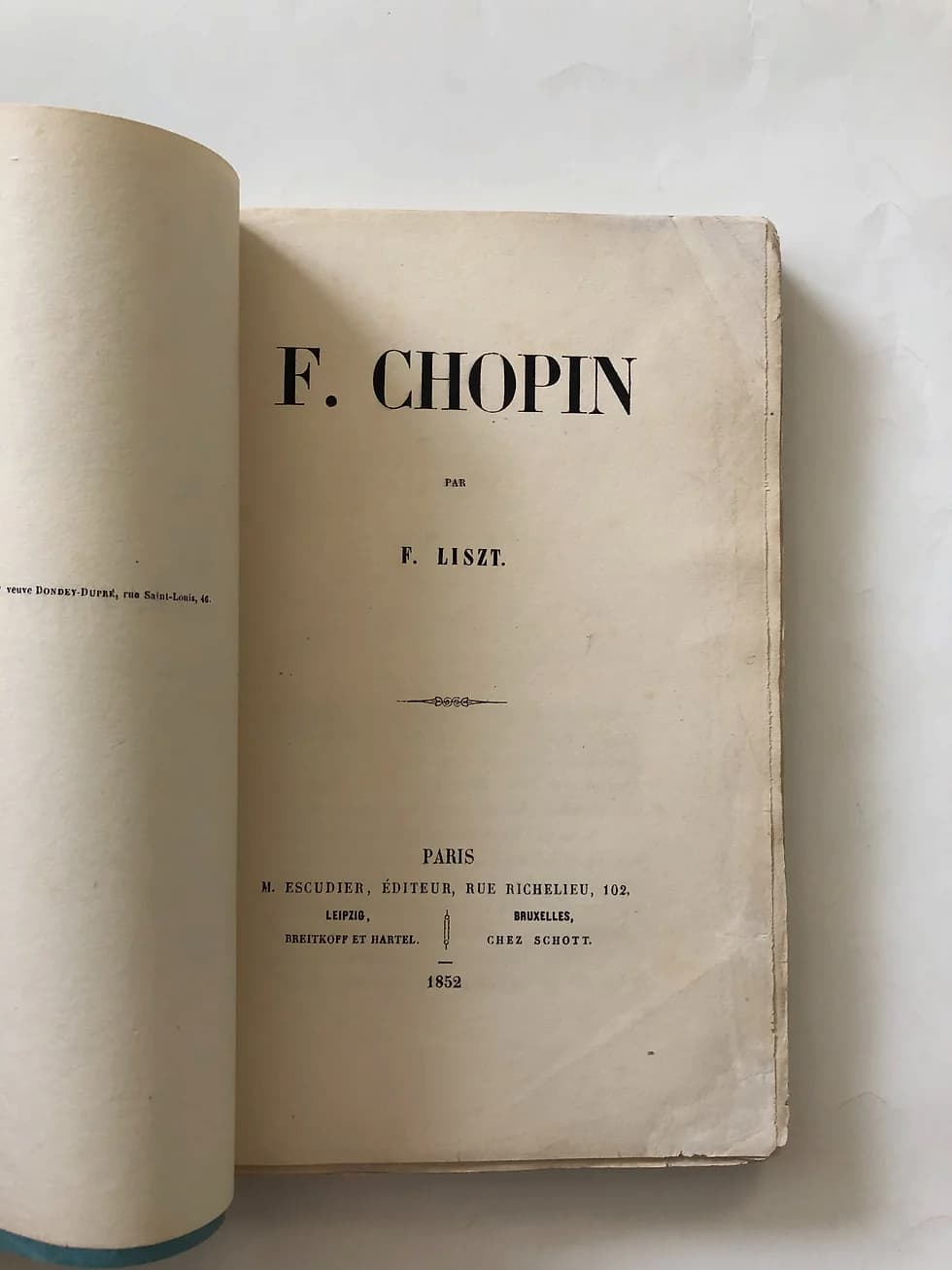

The Chopin Biography

F. Chopin by F. Liszt

A recent study has concluded that the decision to author his book on Chopin was motivated by several factors. Liszt might have felt that with the deaths of Chopin and Mendelssohn, the Romantic movement had lost two seminal figures. Liszt slowly came to feel increasingly alone, “the last remaining representative of a trend.”

Liszt had a very strong sense of artistic heritage that was central to his thinking. Equally important was the teaching of the arts and the circumstances and social role of the artist. As explained, “It was Liszt’s intention to liberate the artist from all limitations and constraints so that he would be able to follow the promptings of inspiration and in doing so, fulfil his calling.”

Liszt set upon the task of writing his Chopin biography without a great deal of details and information. Written in French, it is full of misleading statements while disclosing a number of biographical references. As a scholar wrote, “It should be considered not so much a reliable monograph as the portrayal—complex, at times grandiloquent, at times pathetic—of a great artist and admired friend.

Liszt/Chopin: 6 Polish Songs, No. 4 “Bacchanal” (Geoffrey Tozer, piano)

Critics and Second Edition

F. Chopin by F. Liszt

Liszt was severely taken to task for his Chopin project, “showing abominable taste in publishing a terrible book on Chopin. The small volume was turgid at best, full of useless digressions and misinformation. Today, most musicologists agree that the book was the handy work of Liszt’s mistress, Carolyne Wittgenstein.”

I’ve read the Chopin book, and it is by no means, as bad as some critics have suggested. It is an inspired depiction of Chopin and the world in which he lived. Of course, romantic flights of fancy, veiled interconnections, visions of landscapes, and literary quotations are found throughout. Liszt does reference works by Dante, Petrarch, Tasso, Shakespeare, Goethe, Byron, and Miczkiewicz.

Liszt was aided by his then partner Carolyne Sayn-Wittgenstein, who assisted him primarily with descriptions of the Polish historical background. Initially it was published in instalments, but by 1874 the publisher suggested it be published again in a revised version. And the task of reworking the text fell to Carolyne. This second edition was significantly expanded between 1876 and 1879, and its publication caused a “good deal of misunderstandings.”

Liszt/Chopin: 6 Polish Songs, No. 5 “Meine Freuden”

Polish Song Transcriptions

Franz Liszt and Carolyne Wittgenstein

If Liszt was struggling to put his Chopin biography together, he had no such problems creating a series of six transcriptions from Chopin’s Op. 74. Liszt processed an amazing response to poetic imagery. He strongly believed that purely musical images of poetic ideas were capable of being projected to the listener and that he could illustrate such imagery without words. And in the case of Chopin, the Polish texts would just get in the way. Hardly surprising, therefore, that Liszt provided German titles for his transcriptions.

In the opening “Maiden’s Wish”, Liszt combined the piano part with the vocal part, and the simple melody is treated to three elaborate variations. It illuminates the original text, which describes a girl who, in turn, would be the sun, or a bird, in order to show her love. With its mazurka rhythm, simple and singable melody, it pays delightful homage to beauty and to love. “In Spring” was composed as a lament of one who wanders through a pleasant valley only to be reminded by its beauty of a beloved person who is dead. Liszt provides a simple setting, with the vocal line doubled in octaves, as a lament for a dead lover.

“The Ring” tells of a young man who discovers his ring still on the finger of a young woman, even though she has turned him down and married someone else. The mazurka rhythm makes it immediately clear that this is not a story of sadness but of anger. Liszt seamlessly proceeds to the “Bacchanale,” and an ode to love and wine. Liszt boldly colours the bright and festive melody with glissandos, making abandonly clear that love is much less reliable than drinking.

Liszt beautifully captures Chopin’s mood in his fifth transcription, “My Joys.” It is a passionate song about a beautiful woman and her lover. Liszt provides a sheer lyrical outpouring in almost operatic grandeur, with the lover unable to resist the pleasure of taking her in his arms and wildly kissing her to a mazurka rhythm. In Liszt’s hands, the concluding “Homeward” becomes a short symphonic sketch, fully transforming Chopin’s original compositions. In terms of popularity, Liszt’s transcriptions have far outstripped Chopin’s original songs and have become highly popular encore pieces.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Liszt/Chopin: 6 Polish Songs, No. 6 “Homeward” (Mariam Batsashvili, piano)

Excellent. Illuminating