Throughout the history of classical music, it’s common to find examples of talented sibling pairs. (In fact, we wrote about some of the forgotten musical siblings) Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart worshiped his older sister Maria Anna Mozart as a child, and Felix Mendelssohn did the same to his sister Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel. But did you know that Chopin also had a talented older sister who not only composed, but was a professional writer, too?

Ludwika Chopin Jędrzejewicz

Today we’re looking at the remarkable life of Ludwika Chopin Jędrzejewicz.

Ludwika and Frédéric’s Musical Childhoods

Ludwika Chopin was born on 6 April 1807, the eldest child of teacher Nicolas Chopin and his new wife Justyna. Three more children followed in close succession: Frédéric in 1810, Izabela in 1811, and Emilia in 1812.

Ludwika was a very precocious child. As a child, she studied with a piano teacher named Wojciech Żywny, and she or her mother may actually have been Frédéric’s first piano teacher. We know for sure that the siblings played duets together, and that she helped her younger brother learn French and Polish.

Frédéric proved to be a talented youngster, too. At the age of six, he also began studying with Wojciech Żywny, and he made rapid progress. A year later, he was giving his first public performances, and soon he was composing, as well.

Around the same time, Ludwika also became interested in writing music. In one letter from 1825, Frédéric wrote to a friend, “Ludwika made a perfect mazur, one of the kind that Warsaw has not danced to yet.” Intriguingly, one of the only composers before Frédéric Chopin to write piano mazurkas was a woman: internationally renowned Warsaw-born pianist and composer Maria Szymanowska, who wrote a collection of them that same year. It’s unclear if Ludwika began composing a mazur independently of Szymanowska, or if she was inspired by her countrywoman. Regardless, Ludwika’s interest in the form almost certainly helped inspire her brother’s.

But Ludwika wasn’t just a talented musician; she was also a talented writer. In 1826 she went on a trip with her parents’ friends. They journeyed to Silesia, and she wrote a leaflet about the experience and had it published.

Frédéric’s Career, Ludwika’s Adulthood, and Tsarist Tyranny

Ludwika Chopin Jędrzejewicz with her son Henryk, fragment of a painting by Antoni Ziemięcki, 1833 © culture.pl

In 1830, her brother turned twenty years old. He was coming to an important professional crossroads, and it eventually became clear that he was going to seek his fortune away from Warsaw and his beloved Poland. In March, he premiered his second piano concerto in Warsaw, and he also gave Ludwika a famous gift: the manuscript to one of his C-sharp minor nocturnes, filled with the sadness of imminent departure. On 2 November 1830 he left Warsaw and his family.

Chopin: Nocturne 20 in C sharp minor, Op. posth.

Disaster struck a few weeks later, when on 29 November 1830 Polish patriots began mounting a failed uprising against tyrannical Tsarist rule. Frédéric was deeply distressed that he couldn’t be more involved. He channeled his rebellious patriotic feelings into his music. Meanwhile, Ludwika joined the Polish Ladies Patriotic Charity Union to help victims of Tsarist oppression.

On 22 November 1832, at the age of twenty-five, Ludwika married a lawyer named Józef Kalasanty Jędrzejewicz. The following August, she had her first baby, a son. She would have four children in all.

Many creative women of her era were forced to give up their arts upon getting married or having children, but somehow Ludwika persevered. She put a lot of time and energy into her writing, and came out with multiple books, mainly educational ones for children.

The Death of Frédéric

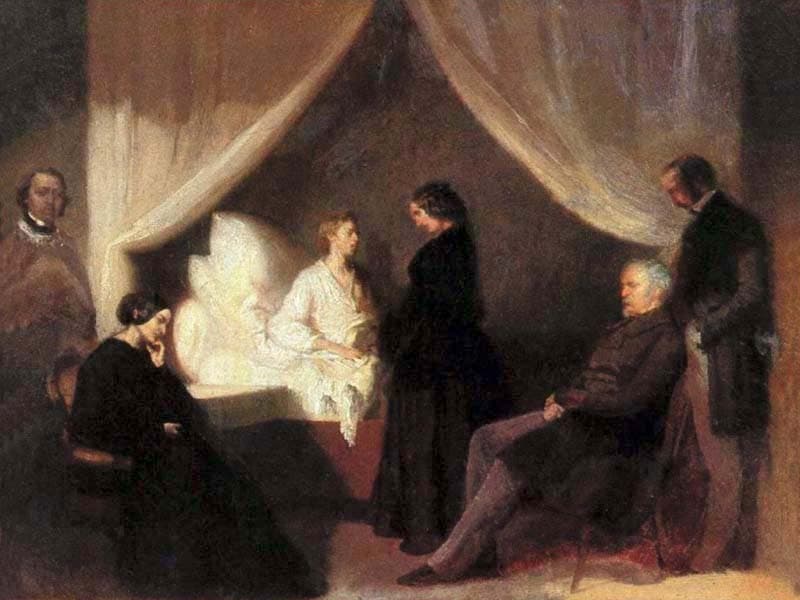

Chopin on His Deathbed, by Kwiatkowski, 1849, commissioned by Jane Stirling.

In May 1844, their father Nicolas died. That summer, Ludwika went to Paris with her husband to visit Frédéric. The siblings had kept up a correspondence but hadn’t seen each other in years. Presumably it was a heartwarming reunion – and it would lay the foundation for another more important visit a few years later.

Frédéric’s health had never been good, and it deteriorated especially markedly in the late 1840s. In mid-1849, he recognized that he was likely nearing the end of his life. He sent a letter to Ludwika, asking if she would come and help him. Despite her husband’s protestations, she left for Paris, arriving at his side on 8 August 1849.

For two months, she nursed her beloved brother in his final illness, a task that must have been overwhelmingly difficult, both physically and emotionally. Frédéric continued to deteriorate, and he died on 17 October.

Chopin’s Final Composition: Mazurka in f minor op.68 no.4

The work, however, didn’t end there: since Frédéric had never married, she also was tasked with sorting through and liquidating his estate. A sale was held at the end of November. A less savvy sibling might have thrown all of his things away, but Ludwika understood the importance of them. Even in her grief, she took the time to sort through and save many important papers and manuscripts, and did her best to ensure that his most important possessions ended up in the hands of people who would appreciate them.

The Tragic Aftermath of Frédéric’s Death

She returned to Warsaw at the beginning of 1850, carrying her brother’s heart with her so that she could honor his final wishes of having his heart interred in Poland. She also brought his correspondence with his famous lover, authoress George Sand. She left the letters with a friend for safekeeping, but tragically, they were intercepted by Alexandre Dumas, Jr., who delivered them to George Sand…who, in turn, burned them.

Simultaneously, as Ludwika grieved the premature loss of her brother, her marriage broke down. Her husband mistreated her, accused her of being too attached to her birth family, and even – bizarrely – spread gossip and rumors about Frédéric. She did her best to attempt to reconcile with him, but he died in 1853.

All of this stress caused her own health to deteriorate. Ludwika Chopin Jędrzejewicz ended up dying in October 1855 during a plague epidemic. She was forty-eight years old, and only two of her four children were grown. One wonders what the next chapter of her life would have been like if she had survived, and what she might have written.

Ludwika Chopin Jędrzejewicz was clearly a hugely influential woman who helped shape Frédéric’s art and career, and was also there for him in his darkest days. She deserves more than a footnote in Chopin’s biography due to her talent, her heart, and her inextinguishable love of country and humanity.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Thank you Emily E; Hogstad for such an interesting and revealing article about Chopin’s sister. As you say, more should be written about her as she was obviously an intelligent, talented and courageous artists and woman.