As we celebrate Camille Saint-Saëns’ birthday on 9 October 1835, we remember a musical genius and the leader of the French musical renaissance during the later part of the 19th century. He composed in virtually every musical genre available to him, and he tellingly wrote, “I am an eclectic spirit. It may be a great defect, but I cannot change it; one cannot make over one’s personality.”

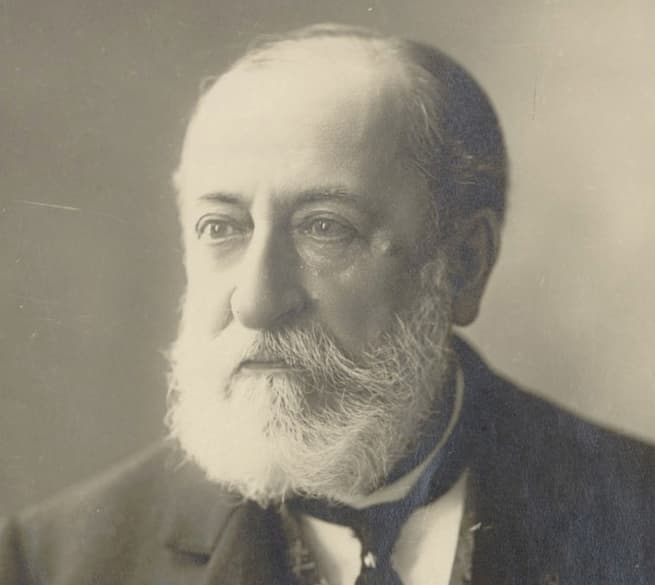

Portrait of Camille Saint-Saëns by Benjamin Constant

Saint-Saëns possessed a mastery of compositional technique, and his ease, ingenuity, naturalness, and productivity were compared to “a tree producing leaves.” Yet, during a period of extreme musical experimentations, Saint-Saëns remained stubbornly traditional, and by the time of his death on 16 December 1921, his compositional style was considered deliberately old-fashioned.

Saint-Saëns never embraced the prevailing aesthetic engulfed by Wagnerian influences, and in his memoirs, he writes, “He who does not get absolute pleasure from a simple series of well-constructed chords, beautiful only in their arrangement, is not really fond of music.” It’s not surprising that he was most successful in works based on traditional Viennese models. As such, we thought it might be fun to celebrate his birthday by exploring his wonderful instrumental sonatas.

Camille Saint-Saëns: Cello Sonata No. 1 in C minor, Op. 32

Saint-Saëns: Cello Sonata No. 1

Composed in 1872, the Cello Sonata No.1 in C minor is Saint-Saens’ first instrumental sonata. It emerged during a year of personal and national crisis. His beloved great-aunt Charlotte Masson, who had been a major force in his upbringing and musical training, died that year. In addition, the French army under Napoleon III had been disastrously defeated at the battle of Sedan. Saint-Saëns had served in the National Guard during the siege of Paris, but following the French surrender, he took refuge in England. Once he returned, he channeled his patriotic energies into the founding of the Société Nationale de Musique.

The Saint-Saëns biographer James Harding writes that in this sonata, “personal emotion, for once, intruded into his music.” The choice of keys might have been inspired by Beethoven, and the C-minor opening allows the cello to make wonderful use of the open C and G strings at the bottom of its range. This stormy work opens with an ominous declamation that paves the way for a journey through ever darker regions. As Steven Isserlis writes, “the prevailing textures lighten only in moments of tearful prayers.

The slow movement is cast in the key of E-flat Major and apparently originated from an organ improvisation in the church of Saint Augustin. Some commentators hear a quotation from Schumann’s song “Wehmut,” from his Liederkreis, Op. 39. The windswept “Finale” exists in two versions, as Charles-Marie Widor relates. After attending the first performance, Saint-Saëns was surprised that his mother hadn’t commented. When he asked, “Don’t you have anything to say? Aren’t you pleased?” Mme. Saint-Saëns responded that she liked the first two movements but not the finale. A few days later, Saint-Saëns produced a new finale, one quoting from the first act of Meyerbeer’s L’Africaine.

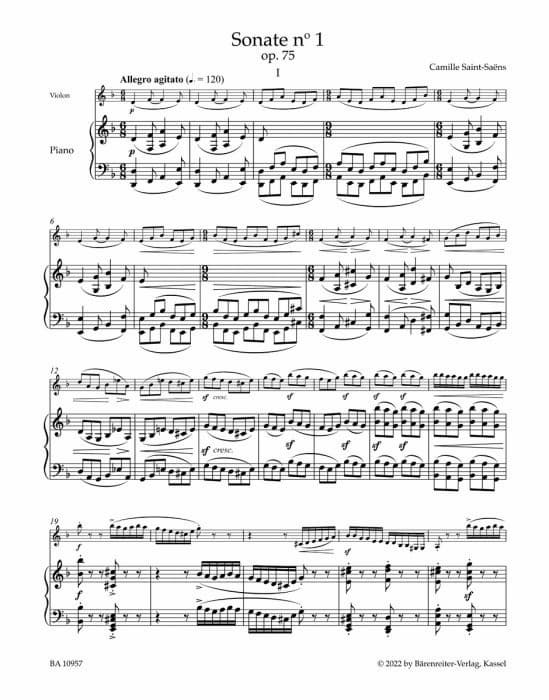

Camille Saint-Saëns: Violin Sonata No. 1 in D minor, Op. 75

Saint-Saëns: Violin Sonata No. 1

French composers wanting to write instrumental music during the second half of the 19th century were confronted by a number of societal constraints. As Saint-Saëns writes, “High society swooned with admiration for Italian music. For the respectable middle class, the real audience, there was nothing beyond French opera and opéra comique. Both sides professed this cult, the idolatry of melody or rather, by the same token, of musical motifs that implant themselves effortlessly in the memory, easy to grasp at the first hearing.”

Although Saint-Saëns had previously written sonatas for violin and piano, he finally published his first Violin Sonata in 1885. At the height of his compositional powers, the work is roughly contemporary with his famous Organ Symphony and The Carnival of the Animals. This sonata is dedicated to the Belgian violinist and teacher Martin-Pierre-Joseph Marsick, with whom he had toured Switzerland the previous year. In fact, Marsick was closely involved during the composition process.

Jean-Pascal Vachon writes, “with hindsight, this sonata can be recognised as a key work in the French repertoire for violin and piano… its boundless beauty, emotional impact and its highly poetic content are served by a perfect mastery of formal architecture.” Scored in four movements, like the “Organ Symphony,” a cyclic theme which is developed and transformed and unites the work from a structural point of view. Saint-Saëns was rather proud of this composition, writing to his publisher, “I believe that this sonata has a future. Its day of glory arrived immediately, and all violinists will lap it up.”

Camille Saint-Saëns: Violin Sonata No. 2 in E-flat Major, Op. 102

Pablo de Sarasate

While the brilliant and virtuoso first Violin Sonata was clearly inspired by unbound Romanticism in the manner of Franz Liszt, Sonata No. 2 for violin and piano in E-flat major, Op. 102, makes a completely different impression. With its regular formal outlines and clear diatonic harmonies, alongside Beethovenian motific developments, Saint-Saëns produced a much more intimate and Classical work. The composer writes, “It is not a concert sonata like the first one, it is very serious chamber music; it will not be understood until the eighth hearing.”

Saint-Saëns was an avid reader and scholar and passionate about history and archaeology. As such, it is not surprising that the 2nd Sonata was composed in 1896 during a winter visit to Luxor in Egypt. It was immediately written before his Piano Concerto No. 5, which is known as “The Egyptian.” It is dedicated to Léon-Alexandre Carembat and his wife Marie-Louise Adolphi, who both won first prizes for piano and violin, respectively, at the Conservatoire in 1883. The premiere was given at the Salle Pleyel on 2 June 1896, featuring Pablo de Sarasate and Saint-Saëns.

A short rhythmic figure dominates the first movement, with continuous modulations frequently stretching into unexpected and unconventional regions. While Saint-Saëns provides a wonderous and richly varied musical tapestry in the opening movement, the energetic “Scherzo” unfolds with classic regularity. It also shows the composer’s growing interest in counterpoint, with a three-part canon sounding in the “Trio.” A breath of tranquillity sounds in the “Andante,” which surrounds a miniature scherzo. The “Finale” is a light-hearted affair, with the rondo refrain separated by episodes of relative relaxation and contrasting tonality.

Camille Saint-Saëns: Violin Sonata No. 2 in E-flat Major, Op. 102 (Ulf Wallin, violin; Roland Pöntinen, piano)

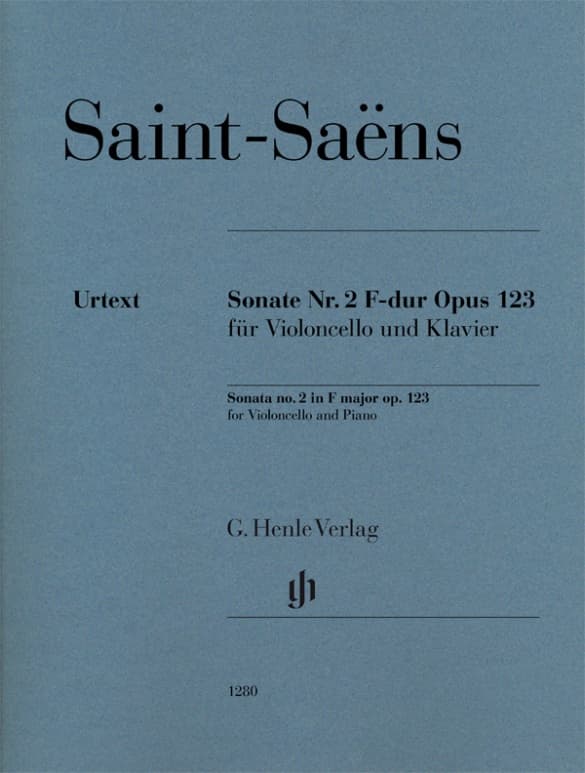

Camille Saint-Saëns: Cello Sonata No. 2 in F Major, Op. 123

Saint-Saëns: Cello Sonata No. 2

Saint-Saëns’ first cello sonata of 1872 had been immediately popular, and the publisher kept pestering the composer to write a second sonata for these instruments. Saint-Saëns finally acquiesced in 1905 when the mild climate of Algeria produced a large sonata in four movements. During the thirty years between this and the Second Sonata, Saint-Saëns had continued to experiment with musical form. Stylistically, his piano writing had become more linear and less heavy, and “this austere tendency serves to emphasise the classical aspect of his nature.”

Saint-Saëns personally thought it superior to his first sonata, and he even believed that the third movement “Romanza,” was an equivalent to the famous “Swan” in the Carnival of the Animals. Romain Rolland described Saint-Saëns as a man “tormented by no passions,” but that’s clearly not born out in the composer’s comments on the work. “Finally it is finished, this damned sonata! Will it please or not? That is the question.”

Saint-Saëns announced the work to his publisher Jacques Durant, and he was pleased about including a fugue as one of the variations of the second movement, while “the last movement will wake anyone who’s slept through the rest of the piece.” The “Romanza” clearly does not align with the composer’s maxim: “never too emotional, never making yourself too vulnerable.” Saint-Saëns continues, “The Adagio will bring tears to your eyes. It leaves you with a feeling that you have been told something important.

Camille Saint-Saëns: Cello Sonata No. 2 in F Major, Op. 123 (Mats Lidström, cello; Bengt Forsberg, piano)

Camille Saint-Saëns: Bassoon Sonata in G Major, Op. 168

Saint-Saëns: Bassoon Sonata

The catastrophe of the First World War cast a gloomy shadow over Europe, further plunging the continent into economic and political uncertainty. And in the last year of his life, Saint-Saëns composed three sonatas for wind instruments: oboe, bassoon and clarinet. A fourth sonata for cor anglais and one for flute was in the making, but it was never completed. Gone are the romantic flourishes and fanfare, replaced with clean lines for the solo instruments and a lighter accompaniment on the piano.

Saint-Saëns retreated into the austere and more obviously French style of music, and these final miniature gems provide ample testimony of his great musical genius, “which remained undiminished even at the age of 86.” The Bassoon Sonata has become one of the most popular works in the entire repertoire by blending a light-hearted style with some peaceful contemplations in three short movements.

In the opening movement, a sparkling piano introduction prepares for a rather funny and high-pitched entrance of the bassoon. However, the music soon turns lyrical, with the piano adding glistening decorations. The bassoon singing out in the high register creates a wonderful and unique atmosphere. Reminiscent of Mendelssohn, the powerful “Scherzo” is full of energy and drive and features characteristic shifts between the major and minor keys. The emotional core of the sonata unfolds in the third movement when Saint-Saëns explores the lyrical qualities of the bassoon. In classical tradition, expressive melodic lines sound over simple accompaniments as the Sonata concludes with an exciting and thrilling final flourish.

Camille Saint-Saëns: Oboe Sonata in D Major, Op. 166

Camille Saint-Saëns © Gallica-BnF

Throughout his life, Saint-Saëns had been an impeccable pianist, and he was intimately familiar with string instruments. Writing for winds, however, he found himself in rather unfamiliar territory. Fortunately, Saint-Saëns had help from Louis Bas, the first solo oboe with the Societé du Conservatoire de l’Opéra and the dedicatee of the work. The composer instantly put his finger on the inflections and special characteristics of the oboe, and his Sonata Op. 166 met with the highest approval of the oboist.

Saint-Saëns was looking to expand the repertoire for the oboe, as he confided to his friend Jean Chantavoine. He writes, “At the moment, I am concentrating my last reserves on giving rarely considered instruments a chance to be heard.”

Two lively outer movements frame an astonishing slow movement in which the oboe’s florid embellishments express nostalgia for nature and the great outdoors. Some commentators heard a vision of Paradise in the opening “Andantino,” and the concluding “Molto Allegro” is an exuberant virtuosic frolic with many exciting scale passages. This is hardly surprising as Louis Bas was famous for the excellence of his scales.

Camille Saint-Saëns: Oboe Sonata in D Major, Op. 166 (Pauline Oostenrijk, oboe; Ivo Janssen, piano)

Camille Saint-Saëns: Clarinet Sonata in E-flat Major, Op. 167

Saint-Saëns: Clarinet Sonata Op. 167

“Not very long ago,” wrote Camille Saint-Saëns, “the name of a living French composer on a poster was sufficient to frighten away any would-be concert-goer.” With indefatigable energy, he worked tirelessly to change that particular image. In addition, he survived domestic tragedy and professional setbacks with an implacable stoicism.

For the musical scholar Jean Gallois, the Clarinet Sonata is the most important of the three wind sonatas. “It is a masterpiece full of impishness, elegance and discreet lyricism summerising Saint-Saëns’ final works for winds.” It is a beautiful and gentle work, full of nostalgic, melancholy, and autumnal glow. Although composed in the first quarter of the 20th century, it clearly belongs to a time long past.

For Sabine Teller Ratner, Saint-Saëns instrumental sonatas “reveal the complete man: his sense of tradition coupled with imagination, his feeling for colour, his sense of humour, his desire for balance and symmetry, his love of clarity. His greatest contribution to music was perpetuating traditional French values during an era of little enthusiasm for instrumental work, and his expert craftsmanship, spirited approach, and Gallic interpretation of Romantic genres provided the new French school of music with foundation and inspiration.” Happy Birthday!

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter