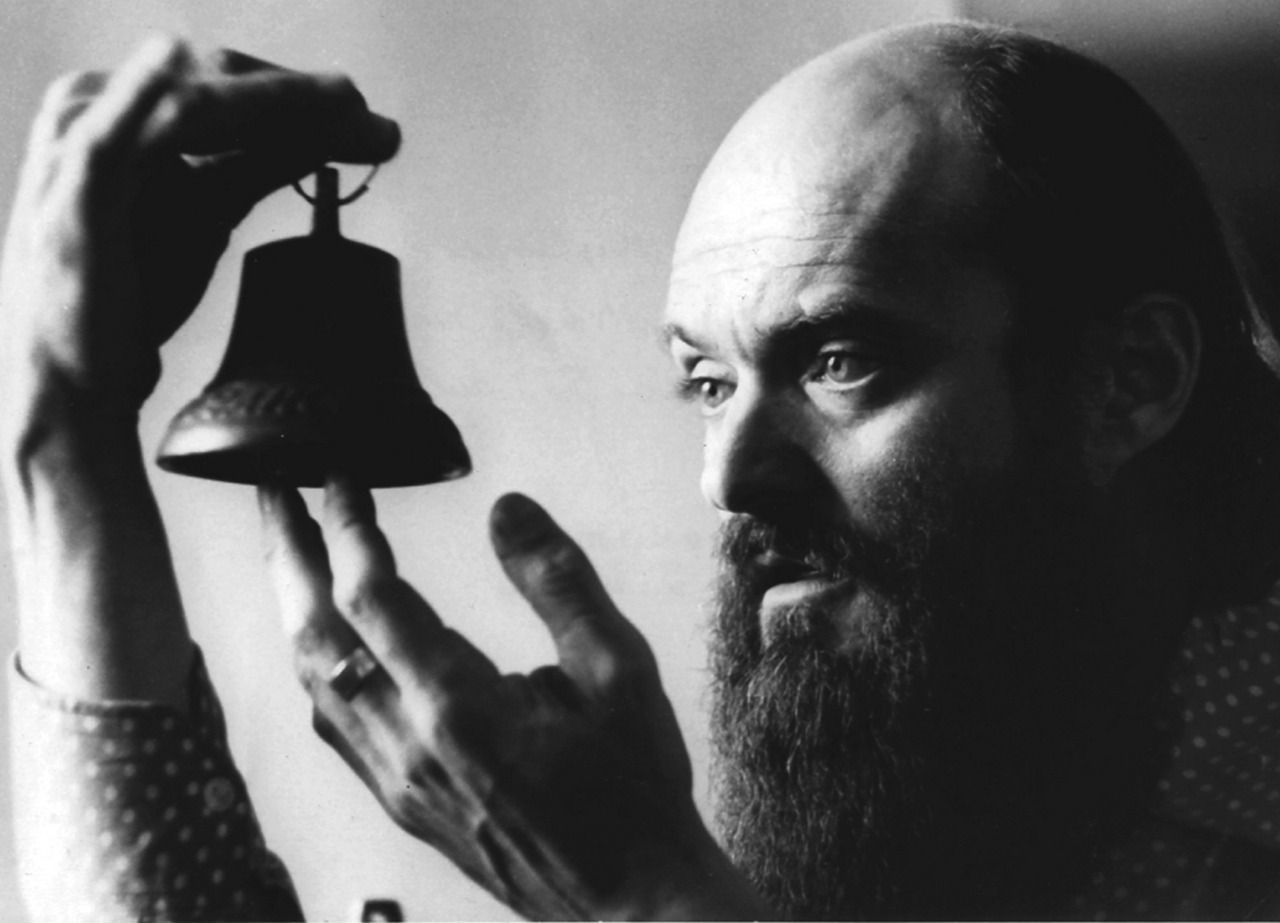

I know it’s hard to believe, but there are still celebrities who wish to keep their public and private spheres completely separate. For Arvo Pärt, one of the most respected and revered composers of contemporary classical music, it is a matter of principle. Pärt essentially lives the life of a recluse, completely shielded and hidden from public view. He rarely talks to the media or gives interviews, and on the rare occasions when he does address the outside world, he comes across as abrasive and belligerent. “I have nothing to say,” he states. “Music says what I need to say. And it is dangerous to say anything, because if I’ve said it already in words there might be nothing left for my music.” There is something contradictory about such an ascetic figure enjoying worldwide popularity, but Pärt philosophy is comparatively simple. “If anybody wishes to understand me,” he says, “they must listen to my music; if anybody wishes to know my ‘philosophy,’ then they can read any of the Church Fathers; if anybody wishes to know about my private life, there are things that I wish to keep closed.”

I know it’s hard to believe, but there are still celebrities who wish to keep their public and private spheres completely separate. For Arvo Pärt, one of the most respected and revered composers of contemporary classical music, it is a matter of principle. Pärt essentially lives the life of a recluse, completely shielded and hidden from public view. He rarely talks to the media or gives interviews, and on the rare occasions when he does address the outside world, he comes across as abrasive and belligerent. “I have nothing to say,” he states. “Music says what I need to say. And it is dangerous to say anything, because if I’ve said it already in words there might be nothing left for my music.” There is something contradictory about such an ascetic figure enjoying worldwide popularity, but Pärt philosophy is comparatively simple. “If anybody wishes to understand me,” he says, “they must listen to my music; if anybody wishes to know my ‘philosophy,’ then they can read any of the Church Fathers; if anybody wishes to know about my private life, there are things that I wish to keep closed.”

Arvo Pärt: Cantus in memoriam Benjamin Britten

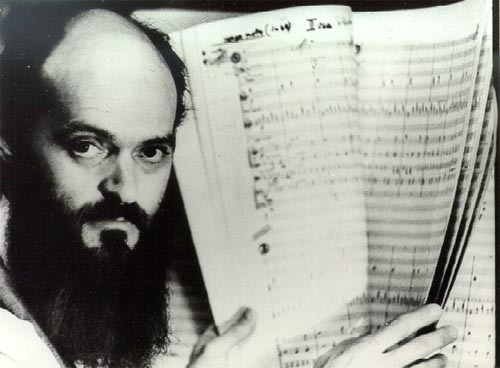

For all intents and purposes, this should be the end of my article on trying to pry into the private life of Arvo Pärt. However, one of the most significant forces that shaped Pärt as a composer and as a human being was his marriage to his second wife Nora in 1971. From the very beginnings as a composer, Pärt had restlessly searched for his compositional voice. Cacophonous experimentations and clashes with Soviet ideology came to a head in 1968, when Pärt completely withdrew from public view. The composer described this period of his life as a “pilgrimage through a desert without knowing whether there will be another side to reach. I think the path that I have searched for and chosen – or maybe it chose me – this path and the many questions that arise from it, this is my contribution.” Pärt has always credited his wife Nora, a trained musicologist, with helping him to find his identity. Her support and contributions find resonance in music that is unbelievably calm and brilliant, placing the listener into a total meditative state. As the famous violinist Gidon Kremer puts it, “It’s a cleansing of all the noise that surrounds us.”

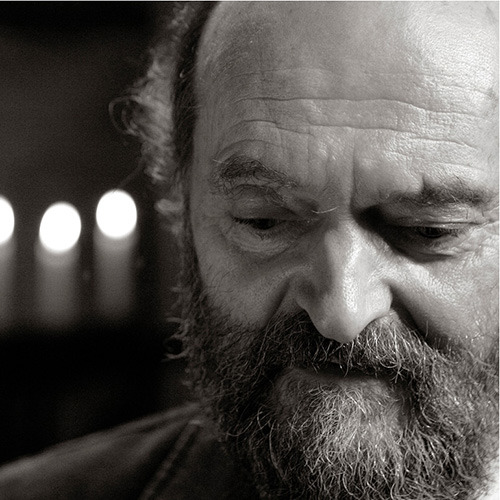

The deeply spiritual and religious dimensions of Pärt’s music did predictably not sit well with Soviet authorities. On the promise of being bound for Israel—since Nora Pärt is Jewish—the couple along with their two sons was allowed to leave the Soviet Union. They carried only seven suitcases, full of scores, records and tapes. When they were detained in a security office at the Brest railway station, one of the guards wanted to have a listen. “We took my record player and played Cantus. It was like liturgy. Then they played another record, Missa Syllabica, and I saw the power of music to transform people.” The Pärt family first settled in Vienna, but soon relocated to Berlin. At the turn of the 21st century, they returned to their native Estonia. Arvo and Nora remain inseparable, and together continue to define their vision of art. “Art has to deal with eternal questions, not just sorting out the issues of today. Art is in fact nothing else than pouring your thoughts or spiritual values into a most suitable artistic form or expressing them in artistic ways. Wisdom resides in reduction, throwing out what is redundant.”

You May Also Like

-

Infinite Reflections: Arvo Pärt’s ‘Spiegel im Spiegel’ Spiegel im Spiegel has to be the best-known of all the music by Estonian composer Arvo Pärt who is 80 this year.

Infinite Reflections: Arvo Pärt’s ‘Spiegel im Spiegel’ Spiegel im Spiegel has to be the best-known of all the music by Estonian composer Arvo Pärt who is 80 this year. -

The early Pärt Living through the political and artistic complexities of the 20th century, Arvo Pärt always sought to communicate the spiritual power that he sees as music’s essential purpose.

The early Pärt Living through the political and artistic complexities of the 20th century, Arvo Pärt always sought to communicate the spiritual power that he sees as music’s essential purpose. -

Arvo Pärt Estonian-born composer Arvo Pärt (1935-) has managed to strike a sound of devotional archaism into a world of chaotic modernity.

Arvo Pärt Estonian-born composer Arvo Pärt (1935-) has managed to strike a sound of devotional archaism into a world of chaotic modernity.

More Love

- Untangling Hearts

Klaus Mäkelä and Yuja Wang What happens when two brilliant musicians fall in love - and then fall apart? -

The Top Ten Loves of Franz Liszt’s Life Marie d'Agoult, Lola Montez, Marie Duplessis and more

The Top Ten Loves of Franz Liszt’s Life Marie d'Agoult, Lola Montez, Marie Duplessis and more - Mathilde Schoenberg and Richard Gerstl

Muse and Femme Fatale Did the love affair between Richard Gerstl and Mathilde Schoenberg served as a catalyst for Schoenberg's atonality? - Louis Spohr and Marianne Pfeiffer

Magic for Violin and Piano How did pianist Marianne Pfeiffer inspire a series of chamber music?