Richard Wagner

Richard Wagner consistently downplayed the significance of his musical education. Undoubtedly, he was very keen to cultivate the notion of the untutored genius, just as Ludwig van Beethoven had done. However, as we saw in our last episode, his first symphonic efforts are technically indebted to his teacher Theodor Weinlig. Stylistically, on the other hand, the influence of Beethoven is undeniable. Above all, these compositions confirm Wagner’s ambition to become the rightful heir to the symphonic tradition embodied by Beethoven. A couple years earlier, around 1830, Wagner had also launched his first operatic attempt. Based on the pastoral play Die Laune des Verliebten (The Lover’s Caprice) by Johann Wolfgang Goethe, young Richard first fashioned a libretto and subsequently composed “a scene for three female voices and a tenor aria.” Wagner seemed to have been rather dissatisfied with his efforts, because neither words nor music has survived. His next operatic project dates from November 1832, and was conceived while visiting the estate of Count Pachta, near Prague. Once again, Wagner fashioned his own libretto for Die Hochzeit (The Wedding), based on a dark medieval tale of murder and treachery. He did start the process of composition, but according to his autobiography “abandoned the composition and destroyed the libretto, because his sister Rosalie objected to the story.” Three musical numbers did survive, among them a chorus and septet, and an introduction.

Richard Wagner, Die Hochzeit

Although Die Hochzeit did not survive, it shares substantial commonalities with Wagner’s next operatic project, Die Feen (The Fairies) of 1833. The two principal characters Ada and Arindal appear in both, and at least parts of the unfinished work may have reappeared in the later project. Wagner fashioned the libretto after Carlo Gozzi’s La donna serpent (The Serpent Woman), a fairy-tale comedy about “a fairy who renounces her immortality in order to gain possession of the man she loves by meeting certain strict conditions. If she fails to meet them, her mortal lover is threatened with the harshest of fates.” This tragic clash between the worlds of humans and of spirits is central to many Romantic operas in the first half of the 19th Century, including Heinrich Marschner’s Der Vampyr (The Vampire) and Hans Heilig of 1828 and 1833, respectively, or Carl Maria von Weber’s Oberon of 1826. These operas inspired not only the words to Die Feen, but also greatly influenced the music.

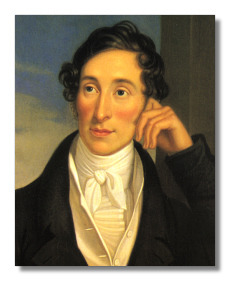

Carl Maria von Weber

Carl Maria von Weber, Oberon, “Overture”

With his opera Hans Heilig, Heinrich Marschner established himself as a leading proponent of German Romantic opera. Following the examples set by Carl Maria von Weber, Marschner drew his subjects from scenes of humble village life in which supernatural beings are projected against a background of mysterious nature. Since human beings, acting as representatives of these superhuman forces, eventually triumph in a vaguely religious concept of deliverance, Marschner artistically mirrored the fervent rise of German Nationalism. His musical language relied on simple, folk-like melodies coloured by an increasingly sophisticated and chromatic language in the orchestra. This emphasis on orchestral colour, achieved through deliberate prominence of the inner voices of the musical texture highlighted an innovative and pioneering handling of the orchestral forces.

Heinrich Marschner, Hans Heiling

Heinrich Marschner

Richard Wagner, Die Feen

Die Feen was not performed in Wagner’s lifetime, and it never established itself in the operatic repertory. However, it marks the beginning of Wagner’s quest for a greater unity of the arts. Wagner had glimpsed this unity in Weber’s Euryanthe and declared, “It is a purely dramatic work, which depends on its success solely on the cooperation of the sister arts, and is certain to lose its effect if deprived of their assistance.” In his next opera Das Liebesverbot (The Ban on Love) of 1834, Wagner assimilated French and Italian operatic styles, and with Rienzi he fashioned a work in the Grand Opera tradition — more about that in our next episode.