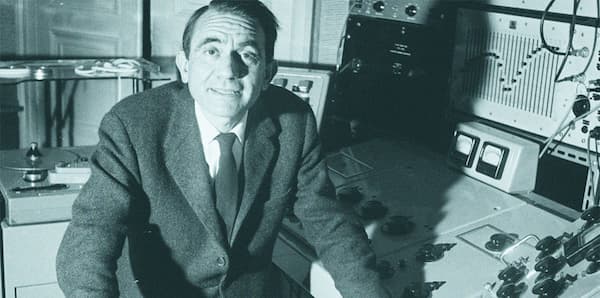

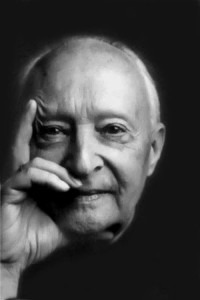

Witold Lutosławski

When you’re asked to think of a twentieth-century composer who uses imaginative textures and sounds, who do you think of? Ravel? Boulez? What about folk melodies – who springs to mind then? Bartok, or maybe Vaughan-Williams? And an innovative harmonic language… Debussy perhaps? Here we find ourselves stumbling upon one of those (unfortunately all-too familiar) cases of a fantastic, highly individual composer hiding somewhere in the background of the twentieth century canon, when in fact they should be out there sharing the limelight. If you haven’t guessed already by my article’s title, I’m of course talking about Witold Lutosławski, whose centenary is this year.

One of the first things that strikes you about Lutosławski’s music is the ease with which he moves around various twentieth-century schools of composition. He can effortlessly combine all the things I mentioned earlier – and that isn’t, of course, to say that he’s the only one who can. There are many other composers who achieve this very successfully, but the point is: why does Lutosławski not get more of a look-in? When is the last time you saw a piece of Lutosławski on a concert programme? Have you ever actually seen a piece of Lutosławski on a concert programme?

I was first introduced to Lutosławski’s music at quite an early age, when I played his Dance Preludes for clarinet, a work that many clarinettists are familiar with. These pieces are highly drenched in folk music from Poland, Lutosławski’s homeland, and all five short pieces have a very light playful character. That is what my perception of the composer rested on until I performed, years later, his Concerto for Orchestra. And then I heard the real Lutosławski. Right from the opening, it grabs you, slaps you round the face, shakes you, inspires and dazzles you for its whole 28-minute duration.

Concerto for Orchestra

If there are positives to be drawn from a composer being relatively unknown, then it’s to do with neutrality. Following the performance of the Concerto for Orchestra, I started exploring Lutosławski’s output. I didn’t really know where to start – but actually, I found that very refreshing. One of the dangers of having a few famous pieces in your oeuvre is that people gravitate towards them and form a large part of their judgement of your whole output based on their experience with a single piece. You feel bad if you don’t get on with ‘the one that everybody knows’… “Well, I listened to the Rite of Spring, but didn’t really like it… But everybody loves the Rite of Spring!” Sound familiar?

I found myself thinking “I’m not too keen on his string quartet, but I’m really enjoying the third symphony!”, and I didn’t feel as though I was missing a point by preferring one work over the other. If I had to recommend something to get your teeth into Lutosławski’s world, it would, however, be the Concerto for Orchestra, for all the reasons above (mainly the grabbing and slapping), although this is of course a tentative recommendation bearing in mind this idea of neutrality…! The reason that, to me, the Concerto for Orchestra is a good starting point is that it seems like a solid milestone between Lutosławski’s earlier and later styles, doing clever things with simple folk melodies but also paving the way (especially in the second movement) for his later works, much of which are based upon aleatoric (chance) operations. If you like the Concerto for Orchestra, there’s a high chance you’ll like a lot else. And if you don’t like it, then that doesn’t matter – you don’t have to! Get out there and get listening!

My main intention in this article wasn’t to shamelessly proclaim the virtues of Lutosławski’s music. Well, actually, it sort of was – and why not? He deserves it. And let’s hope that we all explore a little more often the music of those who perhaps don’t immediately spring to mind – you might be pleasantly surprised with what you find.