French composer Jacques Ibert wrote his Concerto for Cello and Wind Orchestra in 1925 and so much of it reflects the kind of composer Ibert had made himself into. Where we expect concertos to be fairly heavy forms with plenty of opportunities for the soloist to distinguish himself, Ibert’s concerto makes the cello into an extension of the orchestra. Yes, there’s plenty of solo opportunities, but the cello is more a member of the ensemble than the outside battling the orchestral forces.

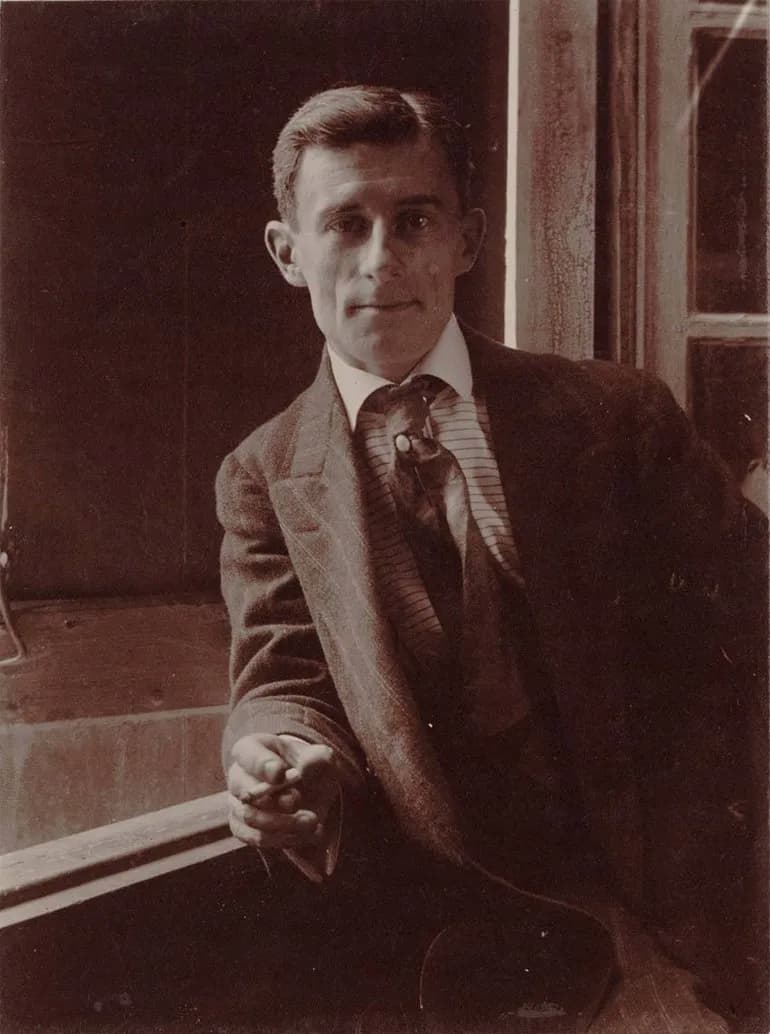

Jacques Ibert

Although Ibert came from a wealthy family, his decision to make his career in music made it necessary for him to make his own way in music. He did this by becoming an accompanist, an extra on stage at the opera, by writing light music, by writing film music, and by accompanying silent films at the cinema. To accompany silent films means being able to develop a character through music alone and this skill Ibert carried through to his serious music.

In the cello concerto, the first movement Pastorale immediately invokes the feeling of the countryside: limpid wind lines intertwine and the flute, the shepherd’s instrument, comes to the fore.

Jacques Ibert: Cello Concerto – I. Pastorale: Allant (Torleif Thedéen, cello; Ostgota Symphonic Wind Ensemble; Hermann Bäumer, cond.)

The second movement. Romance, seems to take its cue from Ibert’s extensive experience in the film world, with a ‘variety theatre’-style accompaniment. The cello seems to be moving alone through a romantic backdrop, but remains fiercely alone.

Jacques Ibert: Cello Concerto – II. Romance: Souple (Torleif Thedéen, cello; Ostgota Symphonic Wind Ensemble; Hermann Bäumer, cond.)

The final movement, Gigue, takes us back to the lightness of the first movement. The cello dances through the movement, with twittering winds around it. We can almost imagine this as a folk dance – with various instruments coming in and out with their special lines. Some of it also sounds like film music – but of a country nature.

Jacques Ibert: Cello Concerto – III. Gigue: Anine (Torleif Thedéen, cello; Ostgota Symphonic Wind Ensemble; Hermann Bäumer, cond.)

Ibert’s Cello Concerto, as a product of the post–WWI 1920s, liberates itself from the normal concerto constraints. The orchestra is small, in this case, mere a wind orchestra; there’s a mix of styles; and we may find that Ibert’s work for cello has more links to an avant-garde work like Stravinsky’s Histoire du Soldat than to older pieces. Monumentalism moves aside for a new minimalist aesthetic. Other cellos works written at this time also reflect these changes: Paul Hindemith’s cello concerto, is simply entitled Chamber Music (Kammermusik No. 3, Op. 36, no. 2); Martinů’s cello concerto, is entitled Concertino for cello, winds, piano and percussion, doesn’t designate the instruments as ‘solo’ or ‘accompanying’, that’s left for the performers to sort out themselves.

Whereas a concerto was traditionally conceived as ‘soloist versus orchestra’, Ibert’s writing seems closer to soloist and orchestra but each with a different part of the story to tell. Ibert’s music has an ‘elegant French lightness’ and does more to redefine the cello concerto for the modern than nearly any other work.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter