Khatia Buniatishvili © Andy Hall for the Observer

Part Two of this article series was originally going to explore the mindset of musicians with regards to financial support during the Covid-19 pandemic – a call to action for artists to choose innovation and creative thinking over consistent begging for help, complaints of being forgotten, or attempts to convince others of our relevance. A call to action to utilise our natural creative skills and devise new artistic concepts (read: revenue streams) to counter those that look down on cultural professions; in doing so negate their main argument that we don’t justify our existence in a capitalist commercial world.

But then I realised the argument was a bit idealistic, unrealistic, flimsy and whimsical (flimsical?) and instead, I was left with an article titled Part One, without a Part Two. And then came Patricia.

Patricia had commented on the first article – read here: exploring what performance garb says about our psychological approach to performance – with a valid point. She wrote:

“You attend a concert for the music not the fashion show. Nothing wrong with tradition and having the musicians blend in to the background to showcase the music.”

I mused on this contribution for a while. Patricia’s comment resonated with some of the other responses to the piece – in essence, that it shouldn’t matter what a musician wears because we are all primarily in service of the music. And she’s definitely not wrong – by inputting performance elements that interfere with what is musically most valid and effective, you risk achieving levels of kitsch instead of quality.

The comment made me think about what exactly ‘showcasing the music’ consists of, and why we as musicians need to be relegated to the background to achieve this. Does the essence of musical performance in fact lie in the passive performer who simply acts as a technician, therefore allowing the music to ‘speak’ for itself? The music that Patricia seemingly referred to is in itself an inanimate object – nothing more than printed notes on a page with a whole heap of subjective historical connotations, which requires an ‘activation element’ in order to be produced outside of the visual realm.

If the primary role of this activation element is putting the music out to be showcased, then we as musicians should have been rendered useless now by technological reproduction – if all we are to do is get out of the way of the music, then we can just programme a score into a MIDI-file and wham, you have it: the perfect, unadulterated version of the music.

Not that anyone actually thinks that MIDI-Beethoven is anywhere near the best way to experience his music. Which suggests that instead, an integral element to a performance is, well, the performer – after all if the music is to be showcased, then it must require something showcasing it. And if the music itself is not enough to evoke emotions (see above clip), then we must agree that it is in fact the personality of the musician that imbues the music with its true value. By saying that the performers need to sit in the background, you are advocating for a mindset that encourages the musician to omit their individual personality and contribution to the music. By asking for minimal individual input in performance, you put a cap on the potential of the work’s true value.

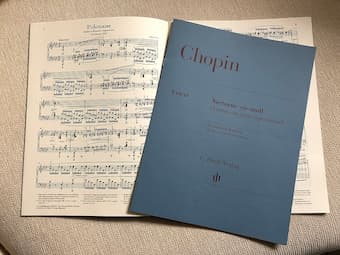

An Urtext edition of Chopin © Wikipedia

In the system of minimal-interference, just how much ‘performer input’ (aka ‘interpretation’) is ‘allowed’? Where is the line that we dare not cross, for fear of enraging those who demand we autonomous musicians satisfy their demands for ‘showcasing the music’? Further, who designated those lines (that is, the traditions there is ‘nothing wrong with’), and who decided they were in the exact right place, and that anyone who steps outside of the boundaries is a heathen who spits on the Holy Urtext?

As musicians, we have readily accepted the memoranda that our individual personalities are subservient to a series of traditions and academic conclusions that render our creative desires moot. Not that I necessarily suggest we start encouraging musicians to do terrible things to music under the banner of ‘free music speech’, but it seems we as an entity have all too happily accepted the requirement of relinquishing any risk in performance by substituting out our personalities in order to ‘let the music in.’ In this sense, we as artists are absolutely part of the servant class: we are specifically not permitted to explore our own creative and musical desires, we are here simply to serve the audience.

And what is the result of our servile mentality? Generations of musicians have now been taught that their ideas are not important, that our personalities are not valuable in this game. And we accept this without question because these are the exact values that are rewarded in competitions and auditions – that is, the best way to secure a stable income. Meanwhile, a small percentage of conservative listeners somehow came to the decision that what they value is the least amount of individualism in music in preference of the safest-option: the lowest common denominator of creating no emotional response is better than having a controversial interpretation. Orchestral and venue managers driven by fear-based and risk-averse leadership listened to them, and decided they preferred an underwhelmed audience to an outraged one. And as a result, all too often we are now left with largely personality-free performances.

Ivo Pogorelich © Mono and Stereo

Have you ever noticed the level of scandal when a performer steps outside of the boundary and tries something different? Compare that to the silence and polite applause that follows a lacklustre, ‘safe’ rendition. I can’t count the number of performances I’ve attended, initially excited at the prospect of hearing something life-changing, and leaving with the distinct dissatisfied feeling that an evening with Netflix would at least have had the potential of delivering some inspiration.

So stay out of the way musicians! Our audience would rather you lull them into a sense of torpor, rather than even risk the potential of dirtying Beethoven with your own personality. In our world, it’s better to feel nothing, then feel displeased.

At this point, I think I’d rather attend the fashion show.

1This article on Khatia Buniatisvhili addresses some of the critiques that come when a musician puts their own agenda on the table. The comments underneath serve to show the response of some listeners.

***This is by no means an attack on Patricia or any other readers/commenters. The author legitimately appreciates her contribution to the conversation, and welcomes others: this is intended to be a healthy debate on a topic we’re all passionate about, rather than yet another thing to be divided on.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

We each choose our path in life. I could have chosen music as I was an accomplished trumpeter. However, I went to Business School and worked in business for my career. Musicians went to music school. They knew what they were getting into. They chose their career path. If you are dissatisfied, how about a career change? Or, how about choosing a different genre that allows more flamboyancy both in attire and performance?